Hint #9 --- Let Evil Be Your Guide

This post was co-published at talanhorne.com.

Welcome back to Hints, a miniseries of Mr. Horne’s Book of Secrets.

Let's face it: you didn't become an author so that you could write someone else's book, and the last thing you need is some concerned third party muscling their way into your creative work and seizing the reins.

Yet you're also not Superman. Striking out into this field without any help is too much to ask of you. But you're not so desperate that you need anyone's advice.

What you could really use...is a hint.

"Hints: because you only need a little help."

Help! My Story is Boring!

Yes of course it is. And you're not alone. It's a near-universal experience for new writers.

Let's see if this sounds familiar: you're knee-deep into your story, and you're just a little bit startled at how well it's going. Your ideas are taking shape. You're having a good time with the setting and plot, and you're starting to feel just a little bit confident.

And then you look back at what you've written, and you really try to read it from the beginning, and you notice something....

That's right, you suddenly realize that the story you have been agonizing over for dozens of hours is a boring slog. You can't even make it to the end of the first page without keeling over, comatose, for a day.

So what went wrong?

Well, it can be any number of things, really. Perhaps your story doesn't really have a direction. Or perhaps your narrative is bogged down with needless description. Or maybe there just aren't enough dynamic events happening to engage the reader.

But most of the time, the problem lies with your characters.

If the characters are not interesting then nothing they do, no matter how explosive, will be enough to hold the reader's attention. If the character is a stranger we know nothing about, then it really doesn't matter what happens to them. More importantly, if the reader cannot form an opinion about the character, then they have no reason to exist.

And that is one key that bears repeating: the narrative strength of any character is directly correlated to how easy it is for the audience to form an opinion about them.

Naturally, there are many ways to do this, with the most common answer being that you need to make the character relatable. For, according to conventional wisdom, if the reader can see themselves in the character, that is the best way to get them to care about the character's fate.

But Conventional Wisdom Is Wrong

Not diametrically wrong, of course. The thrust of its argument is in the generally correct direction.

But it's dangerous to assume that relatability is the only way to make a great character. And to make such an assertion obscures the real law of character development, because why should you settle for the approximate truth when the genuine article is available?

Because the real way to ensure the audience cares about a character is to make that character do things the audience cannot feel neutral about. That may, in some cases, involve the character doing something to make them relatable, but not always.

For example, most people will not relate to being a bank robber. Yet bank robbers make compelling protagonists, simply because as soon as the reader finds out that a character is a bank robber it is impossible to have no opinion of them. The resulting opinion may be good, or it may be bad, but it is always captivating.

Which brings us to the real takeaway of this whole exercise.

Looking for a Shortcut? Use Evil.

Inasmuch as this blog post is a hint and not advice, it make sense for me to cut to the chase and give you the life-hack version of making interesting characters. And that life hack is called "evil".

A great deal of fiction focuses on the problem of evil. Evil is intractable. It has no easy answer but always lends itself to great and terrible consequences. And because of that, it never fails to be interesting.

A simple exercise that guarantees the creation of interesting characters is this: whenever creating a new character, ask yourself, "In what way is this character a bad person?"

Oh, You Mean, "Give Them a Character Fault."

No. That is most certainly not what I mean.

Because a fault is not necessarily a sin. EVERYONE has faults, but not everyone is a bad person. And while sins can only be deliciously interesting, character faults can conceivably be mundane and weak.

Take, for example, the following faults:

- The character cares too much.

- The character is just too derned nice.

- The character is physically weak.

- The character is intellectually weak.

- The character is too young or too naive to undertake the task required of them.

- The character just doesn't know how beautiful she is. And she has no idea why the narrative keeps presenting her with a menu of super-hot boys who are all interested in her, or why each romantic option is strangely consequence-free, even when she mixes herself up with the law-breaking bad boy or the obsessive stalker billionaire. And really, she just wishes that people would stop paying attention to her and leave her alone, because she's totally not conceited like all the other beautiful girls in the story, and having a relationship with the one guy all the other girls want really isn't that important to her. Really. Pinky promise.

All these faults keep the character from being perfect while adding nothing to their appeal. Because a faulty character who is still a good person is not strong enough to drive a narrative.

But suppose we take the above faults and turn them into all-out sins. Watch what happens:

- The character cares too much, and as a result starts meddling in the affairs of others. The rights of these other people is never considered. She is determined to "fix" these people at any cost, even if it means committing horrendous acts, destroying lives, relationships, and families.

- The character is just too derned nice, and therefore does not speak up when terrible things start to happen to friends and neighbors. It hardly matters if people all around him are getting hurt. He is determined not to stir the pot, and not put forth any effort to stop the tragedy from repeating itself endlessly.

- The character is physically weak, and because of that he despises the strong. In those rare moments when he is given power over others, he uses it to torment them, exulting in his leverage with a fiendish glee.

- The character is intellectually weak, which keeps him from trying to make a better life for himself. After all, he's too much of a dummy to ever have a chance at an honest living, so he keeps committing petty crimes to get by. He doesn't need a fancy degree for that.

- The character knows exactly how attractive she is, and she uses that power to manipulate men into fighting an even dying for her.

And here's the thing: any of the above characters can be the hero of your story. Villains do not (and I dare say, should not) have a monopoly on evil. It should instead be part of your recipe when designing every character in your repertoire.

Using evil as your guide gives you a head start that most amateur writers don't know about.

Shakespeare Did It First

Though I don't often invoke the Bard on my blog, his example is helpful for this particular hint.

All of Shakespeare's characters were bad people, including his heroes. The most admirable among them was still subject to their own favorite vices---a fact which his villains are all too quick to capitalize on.

Iago is scheming traitor, but Othello is a jealous and unforgiving lover. Caliban is an uncivilized animal, but Prospero is a cruel and manipulative master. Brutus is treacherous and ungrateful, but Caesar is arrogant and narrow minded.

And while "Shakespeare did it, so it must be good" is hardly an airtight argument, we can see how his work benefited and was enriched by removing all pretense of saintliness from his characters, whether they be the ones we're meant to root for or the ones we're meant to despise.

And I would hope that anyone who reads this hint will see how it applies to their own writing.

Conclusion

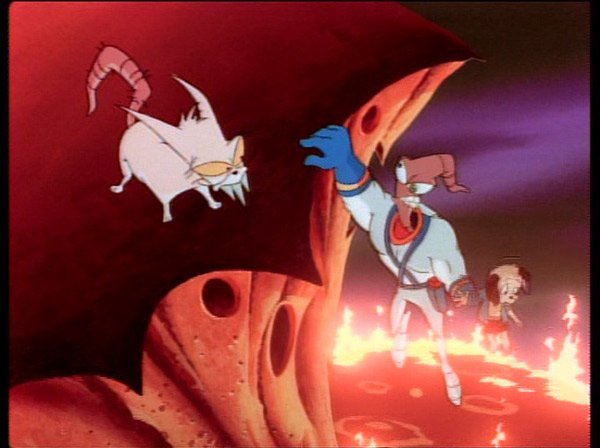

Fiction is about bad people. It has to be, because if they're not bad, then they're not interesting. This holds especially true for heroes. Heroes are mischievous. They're often up to no good. At some point, if the story is any good, your hero will do something naughty.

In which case, if you nail down your hero's personal sins before you even start writing the book, you will be so much the better off when establishing his character and slowly building him up to those transgressive moments when he does naughty things, making his overall development that much more natural and organic.

It may seem like a stretch, but believe me when I say it will make your stories a thousand times more dynamic and eye-catching. And in a field as competitive as fiction, you need all the advantages you can get.

@talanhorne,

Nice guide, good article after a long time period!

Cheers~

Good writing knowledge sir. this is great article and thanks for sharing

Thanks @talanhorne

Have a wonderful day.

A little bit long but so fun to learn i mean your words gave me a clear idea. Regards

Excellent review @talanhorne and you are right, when creating a character for a book you need to show it from different sides!

great writing my dear friend and very nice photos

great work

thanks and good day

Very interesting writing i must say... keep it up.👍

Hi @talanhorne, you're right when you say:

(Fiction is about bad people. It has to be, because if they're not bad, then they're not interesting.)

what really attracts the general public is precisely this, to be a hero you have to fight against evil and overcome it, if the content is different I do not think it attracts many followers, that is human nature.

Great to check this out a nice way to enjoy the week :D

What a great writing and nice photos you have shared here

Hi talanhorne,

Visit curiesteem.com or join the Curie Discord community to learn more.