The Charleston Workhouse: A Legacy of Control and Punishment

The Charleston Workhouse, located on Magazine Street in Charleston, South Carolina, was a notorious institution of southern slavery. Established in 1736, the Workhouse was founded not merely as a correctional facility but as a tool for maintaining the oppressive social order of slavery. Though it later gained infamy for its brutality, the roots of the Workhouse were embedded in a larger framework of economic exploitation, racial control, and colonial social policy. Understanding the foundation behind the Charleston Workhouse is essential to grasping the deeper forces that shaped its existence.

In the early 18th century, Charleston was a booming port city built on plantation agriculture and the labor of enslaved Africans. As the enslaved population grew, so did the anxieties of white enslavers who feared rebellion, escape, and resistance. Maintaining order over this population became a key concern for city officials. The foundation of the Charleston Workhouse was part of a broader effort to establish control mechanisms that reinforced the institution of slavery and suppressed dissent.

The first Charleston Workhouse was modeled after English poorhouses. These facilities, which were intended to house the poor and enforce discipline through labor, were adapted in the American South for a different purpose. In Charleston, the Workhouse was initially meant to care for impoverished individuals but was quickly converted into a facility for detaining enslaved people—particularly those who had attempted to escape or were considered “unruly” by their enslavers.

By 1740, just four years after the Workhouse was established, South Carolina passed legislation that required all captured runaway enslaved individuals to be confined in the Workhouse until they were claimed by their enslavers or sold. This legal shift marked a transformation in the Workhouse’s purpose: from a temporary poorhouse to a key component of the slave system. Enslavers could now legally rely on the state to punish and control those they had enslaved, outsourcing the violence and discipline that kept the system functioning.

The facility was situated at the southwest corner of Magazine and Mazyck (now Logan) Streets and also served as a public hospital during its early years. However, in 1768, a separate hospital was built for white paupers, and the Workhouse was thereafter used exclusively for punishing enslaved people. This change reinforced the racial segregation and dehumanization that underpinned the institution.

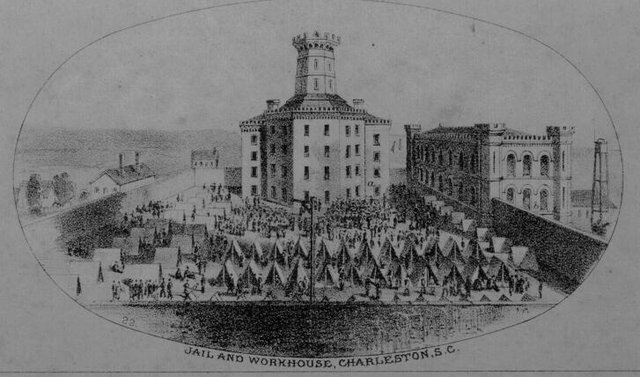

Following a fire in 1780, the British military—then occupying Charleston during the American Revolution—relocated the Workhouse to a former sugar refinery at the west end of Broad Street. After the war, the city continued to operate the Workhouse, eventually returning it to its original location in 1786–87. By 1804, it was permanently situated next to the Charleston District Jail, though the functions of the two buildings were not connected.

The foundation of the Workhouse was not just about punishment; it was about profit and social order. Enslavers paid fees to have enslaved individuals punished—25 cents for up to 20 lashes, and more for additional abuse. The Workhouse also held enslaved individuals awaiting sale or return, making it a hub in the broader economy of human trafficking and labor exploitation.

In 1825, the addition of a treadmill—originally designed to grind corn—turned punishment into a form of grueling forced labor. Enslaved individuals were made to walk for hours on end, often suffering exhaustion, injury, or death. The Workhouse thus functioned as both a penal institution and an economic engine built on suffering.

The foundation behind the Charleston Workhouse was never humanitarian. From its earliest days, it was designed to support the institution of slavery through violence, legal enforcement, and profit. Its transformation from a poorhouse to a center of punishment for enslaved individuals reflected the racial ideologies and economic motives of the time. Though it was destroyed in the 1886 Charleston earthquake and never rebuilt, the Workhouse remains a symbol of the systemic cruelty embedded in the foundations of American slavery. Its history serves as a stark reminder of how institutions can be weaponized to uphold injustice—and how essential it is to confront that legacy today.