Terrible Transgender Jokes:Dave Chappelle did not listen

On August 1, Dave Chappelle began a series of 16 shows at New York’s Radio City Music Hall. Checking my Facebook feed that evening, I saw some disappointingly predictable news: despite widespread criticism of his first two Netflix specials, “Deep in the Heart of Texas” and “The Age of Spin,” he had not stopped telling transphobic jokes; in fact, his new show reportedly opened with 20 whole minutes of them.

The next evening, someone linked me to a different review of the first show and pointed out something more surprising: Dave had mentioned a fan writing him a letter about his trans jokes.

That fan was probably me.

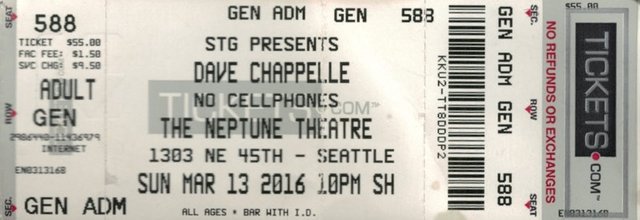

Back in March 2016, I attended the first of Dave’s four shows over two days at the Neptune Theater in Seattle, Washington. At its best, the show was a uniquely intimate experience, with Dave eventually dropping the pretense of a traditional rehearsed routine, sitting on the edge of the stage and interacting directly with the audience. Despite signs everywhere warning attendees not to interrupt the performance, he chatted directly with the crowd about a few subjects, including the (then-)upcoming election and the legacy of Bill Cosby. Some of this material, especially his thoughts about Cosby, had a confessional quality in which he struggled to find a balance between extremes.

At another point in the show, he also performed some material about his wife’s gay friends. This was lightly confessional as well, with Dave admitting it took him a long time to understand gay men, describing how he slowly became more comfortable with their presence. It was heavily flawed (he affected a stereotypically effeminate voice when recounting something a gay man said, and expressed wariness at gay political causes), but there was at least a mild sense that he was trying to push back against his set ways in order to expand his horizons, and I respected that.

What I didn’t respect was the lengthy segment on trans people, which started with complaints about Caitlyn Jenner ruining his memories and got worse as it went on. He began by deadnaming and misgendering her, reminiscing about seeing “Bruce on the Wheaties box” as a child, with his retrospective horror at admiring a trans woman serving as the punchline. He trashed the notion that trans people experienced similar or worse types of discrimination as the black community. Finally, he closed the subject with an imagined scene about a trans woman “tricking” a man into having sex, a familiar transphobic trope. Throughout, Dave used the slur “tranny” instead of “trans.”

Although Dave is most famous for “The Chappelle Show” and the stoner comedy Half-Baked, my personal introduction was the 2006 Michel Gondry documentary Dave Chappelle’s Block Party. It’s a celebratory, joyous movie, in which Dave warmly invites people from his hometown and from around New York City to a secret festival filled with some of his favorite musical acts, including Kanye West, Erykah Badu, Mos Def, and a reunion of The Fugees. The movie is funny, exciting, politically charged, and even heartwarming, as Dave interacts with the performers and the wide demographic range of regular people he’s invited to either watch or play a part in the all-day show, staged in the heart of Brooklyn’s impoverished and increasingly gentrified Bed-Stuy neighborhood. In one segment, Dave gets to know Arthur and Cynthia Wood, eccentric owners of the Broken Angel House, a wildly unique blend of found structure and architectural sculpture located on the street where the block party is being held (now tragically torn down, but immortalized in the movie); in another, he visits the school Biggie Smalls attended when he was a child and speaks to one of Biggie’s childhood friends. Through Dave’s excited and genuinely enthusiastic interactions with anyone with something interesting to say, the film lives up to its title by feeling like a big party the viewer has been invited to, with the comedian as the generous and welcoming host.

Since this film formed the core of my impression of Dave as a performer, it was especially disappointing to hear material that was so regressive, exclusionary, and cruel. Worse, while the globally -distributed Netflix specials finally prompted widespread complaints about the material, comedy fans have been criticizing Dave for similar material since before his previous 2014 Radio City Music Hall residency in 2014.

The majority of the Seattle set was very funny. At times, Dave moved around on the stage with the sharp, almost cartoonish energy that gave his sketch comedy such a potent punch. Later, after he sat down, he managed to generate a communal atmosphere that evoked Gondry’s documentary. Yet, even though the night was mostly enjoyable, the transphobic material weighed heavily on the overall experience.

I had brought my Block Party DVD hoping to get it autographed, but I was unable to catch him as he left the venue. I decided to mail the cover to his next venue in Portland, and write him a letter along with it. I wrote the letter by hand, without drafting it first. (If I’d known it would potentially be notable in the future, I would’ve typed it up!) In it, I praised the same things I’ve praised above but offered tempered criticism about his trans jokes. I cited his admission that he was working through his homophobia as another instance in which he’d admitted he was slow to change. I pointed out that black struggles and trans struggles, which he tried to rank against one another, are not mutually exclusive, as many trans women are also black women, and they tend to face the worst and most violent forms of discrimination. I mentioned that I have a friend who is a trans woman and also a stand-up comedian, in hopes of inspiring some professional understanding. Finally, I discouraged the use of the word “tranny.” While correcting this terminology wouldn’t fix the deeper problems with the jokes, elaborating further felt too complex to tackle in a one-way conversation.

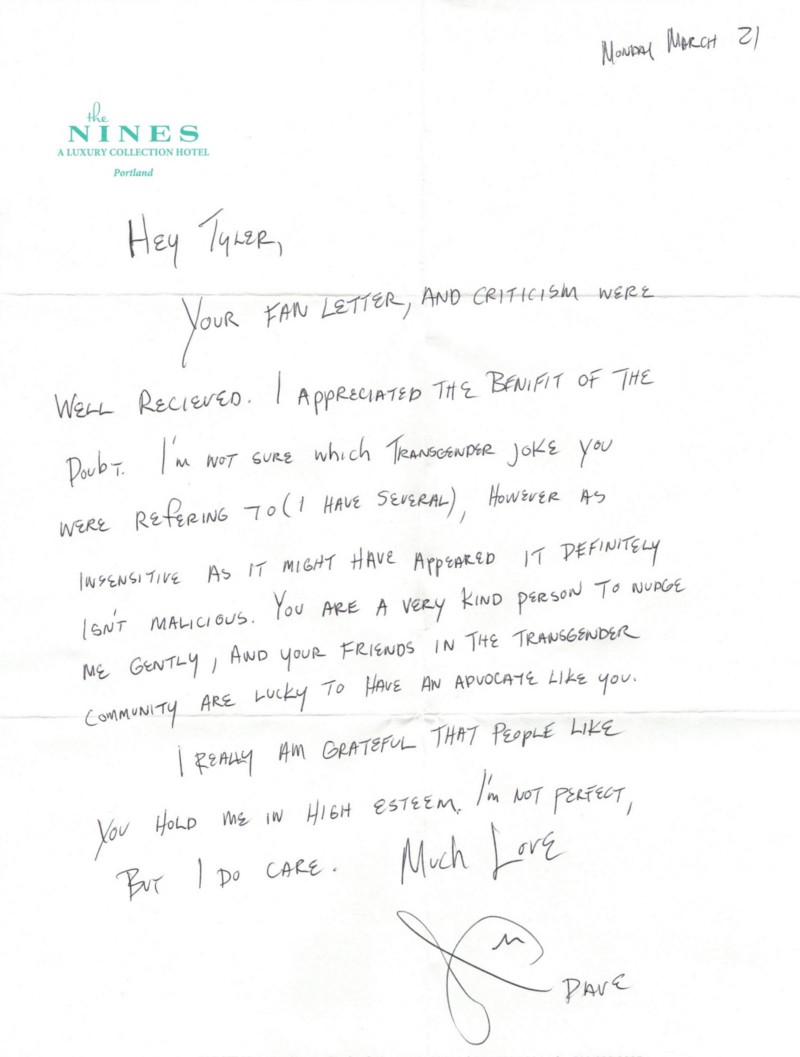

In all honesty, I didn’t necessarily expect to receive anything in return, but a few days later I found my return envelope in my mailbox, and Dave had included a handwritten reply letter on hotel stationery. Here is that letter:

Hey Tyler,

Your fan letter, and criticism were well received. I appreciated the benefit of the doubt. I’m not sure which transgender joke you were referring to (I have several), however as insensitive as it might have appeared it definitely isn’t malicious. You are a very kind person to nudge me gently, and your friends in the transgender community are lucky to have an advocate like you.

I really am grateful that people like you hold me in high esteem. I’m not perfect, but I do care.

Much love,

Dave

At the time, I wanted to believe what Dave wrote. Although he didn’t respond directly to what I had written, I hoped that my overall points had left an impression on him. Sadly, based on the review of his Radio City Music Hall performance, even if he was affected by it, he simply used it as material to segue into even worse Caitlyn Jenner jokes than the ones he performed in Seattle. In fact, despite his statements in the letter that his intent “isn’t malicious” and “I do care,” his transgender material has only gotten more hateful across the board.

When Dave performed in Seattle, the material was demeaning and dismissive, but two out of the three segments at least offered perspective on things that were personal to him. While it’s disappointing that his only takeaway from remembering Jenner’s Wheaties box is regretting that he idolized her, age affecting the perception of childhood memories isn’t an unusual premise. It’s also understandable that Dave has a personal emotional investment in the struggles of the black community. However, explaining that trans people are also harassed and murdered by bigots isn’t meant to minimize black suffering, but rather to point out the crossover, both in terms of the victims and the basic similarities of systemic social oppression.

Still, those jokes are a relief compared to a routine in “Texas” where Dave’s willingness to help a trans woman in need of medical attention is essentially contingent his freedom to misgender her, or the bit from the Radio City Music Hall review where he expresses revulsion on behalf of the audience (“I figure I’d just say it for everybody — yuck”) at the idea of Jenner posing nude in Sports Illustrated. These segments don’t stem from anything personal beyond his own disgust, offering no insight into his perspective other than his insistent dismissal of trans people as human beings worthy of respect, no matter how often he adds he’d never do that.

Just a few days before Dave’s residency started, another comedian named Lil Duval made headlines for his insistence he’d murder a woman who slept with him and then revealed they were trans (a sentiment which, based on Duval’s comments, is also rooted in misplaced homophobia). Duval’s comments (which he reiterated days later, after a severe backlash) were sincere, but his tone places those statements in the framework of “telling it like it is” comedy: confessional, honest statements that draw laughter from the audience’s recognition of similar thoughts or feelings. Whether he believes it or not, Dave’s comedy feeds into the same hateful ideology about trans people as Duval’s comments, reaffirming the audience’s fear of people who are different from them, while pushing trans people’s real problems to the side and treating them without dignity.

On December 31st, Netflix added two more specials by Chappelle, “Equanimity” and “The Bird Revelation.” In the former, he repeats the routine involving my letter, although now he characterizes it from being a white trans person (I am neither), and claims that the fan found him under a fake name to send it to the hotel (I sent it to him under his real name, via the venue where he was performing), although he does include the fact that he received it in Portland, and that my criticism wasn’t over a specific joke (which he mentions in the actual handwritten reply he sent).

He confesses that while he never feels bad about his material, he does say, “I felt bad that I made somebody else feel bad.” To some degree, that feels like it has to be true, or the letter and the commentary on the letter wouldn’t have made it into his act. He mentions in the bit that he doesn’t read much fan mail, which adds to the likelihood that the criticism stood out to him. He’s even shifted to saying “trans” instead of “tranny,” which is a relief (even if he occasionally occasionally uses “transgendered” instead of “transgender”). Yet, the entire segment talking about the letter was, and remains, a long set up to more of his trans material. Weirdly, the rewrite makes the bit even more dismissive, ignoring a complaint ostensibly from someone directly affected by the material rather than a bystander like

myself.

The “Equanimity” routine is framed by the last and most reliable line of defense against hurtful comedy: that comedy is essentially an act of rebellion, a First Amendment expression of unfiltered insight. In short, it’s meant to be “offensive.” The problem with this argument is that “offensive” is an incredibly broad term. It is easy to say that widely-praised comedians and material such as George Carlin, the profane political satire In the Loop, or even the best material from “Chappelle’s Show” are “offensive,” but what matters is: offensive to whom, and in service of what?

The artistic goal of a comedian is not simply to get a laugh, because laughter is little more than a reflex. A comedian, like any artist, should be trying to say something, and it matters what that something is. That something reflects a worldview, a perspective, a person, and what Chappelle needs to realize is that while a comedian has no obligation to tell the truth about themselves with their material, the 180-degree difference between his comments to the Washington Blade (“I’m not an obstructionist of anybody’s lifestyle, as long as it doesn’t hurt me or people I love and I don’t believe that lifestyle does.”) and his current material — which is hurtful in exactly the same way he claims struck a chord with him — is impossible to resolve.

Thanks to Liane Behrens for helping me edit this piece.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://medium.com/@tylergfoster/i-wrote-dave-chappelle-a-letter-about-his-terrible-transgender-jokes-55478970b9f