When the magic circle collapses

(cross-posted from my Substack)

When the magic circle collapses

Does philosophy of games say anything useful about fun?

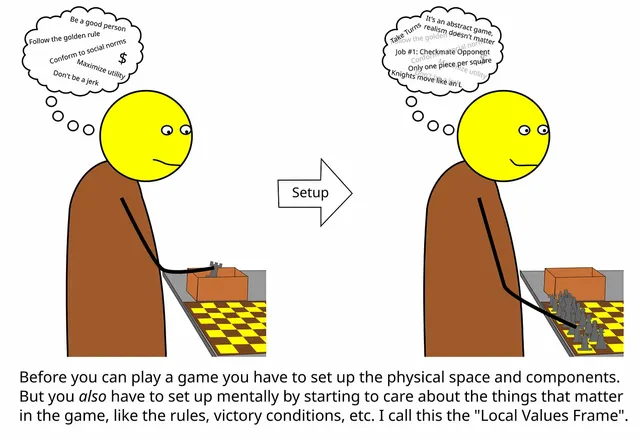

My current philosophical model is that games are about exercising agency in a local values frame.[1] I think of this model as building on the ideas put forward by C. Thi Nguyen in the book Games: Agency as Art, which built on the ideas of Bernard Suits in The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia. By “Local Values Frame” I mean that playing a game involves temporarily caring about things that matter inside the game that don’t matter outside of it: while you’re playing a sport one section of ground may be in-bounds while another is out-of-bounds and that’s important, but if you’re not playing it doesn’t matter because it’s all just the ground. In a competitive game you value things like “points” and “winning” during play but afterwards they may not matter at all, and even be forgotten immediately.

Local? Values?! Frame?!

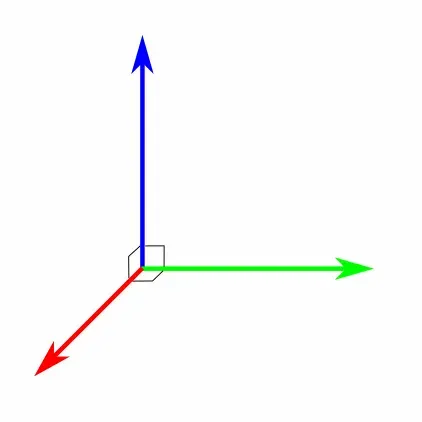

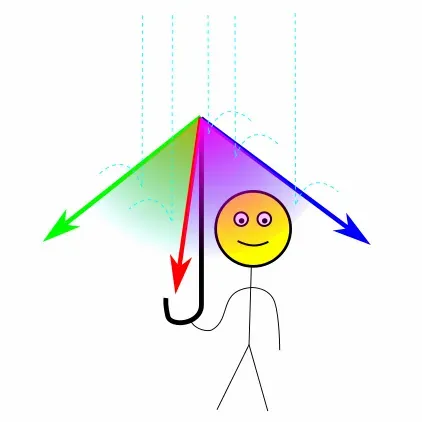

I say they’re local (as opposed to global) because they only matter within the small context of the game. And I think “values” is a good word to capture things like “it’s good to have more X, it’s bad to have more Y” and “it’s important to follow rules A, B, and C”. In normal life we could talk about whether people value material possessions or having a good reputation, and how people’s moral values guide them to follow certain practices. The “local values” of the game are like that, but based around the particulars of the game. And I call them a frame based on things like the “stack frame” that a computer program uses for the local variables of a function, or a story that happens within the context of a “frame story”, and also because the values are a framework that connect together to create the space you’re in. Not every set of “local values” works exactly like an orthogonal physical dimension, but some do, so I find that to be a useful visual metaphor: the local values set up a frame that defines a space.

Mentally entering that space is what I think we mean when we that you “step into the magic circle” when you start playing a game. And setting it up creates the space in which you can exercise agency, things like taking actions or making choices.[2]

I think I’m on pretty safe ground with what I’ve said so far, I think Games: Agency as Art made a pretty good case for its model, and I think of the model I’m presenting here as a superset of that because it just takes the idea that a game has a defined end-goal and generalizes that out to say that’s one way that a game can set up its values frame but there can be others as well.

Games Just Wanna Have Fun?

Defining “games” is fraught, but let’s go even further and talk about “fun”. The structure of the original Suits definition doesn’t require the game to be fun since it also covered things like playing for achievement (such as an Olympic athlete) or playing professionally (such as professional football or poker players), while they may be having fun while playing it isn’t a requirement, it would also be valid to say they’re playing a game even if they find the activity an un-fun grind but merely do it for the glory or the money. But I think the paradigmatic game is expected to be fun while playing it, and there are some un-fun experiences that seem like they might be related to the definition/model.

Solved games

Connect 4 is a solved game. There’s an algorithm that the first player can use that, if followed, guarantees that they win. Knowing this I can’t have fun playing the game (I wouldn’t say it was greatest game even before I knew that, but at least fun could be had). I think what’s happening is that you can’t simultaneously care bout winning and make agentic choices. If winning matters you should follow the guaranteed-win algorithm, or you can make your own choices with some goal other than winning (maybe expressing some style), but you can’t do both at once. Your agency either moves you outside the values frame, or else you stay in the values frame but there’s no room for your choices.

Pro forma progression toward a foregone conclusion

There are some game situations where it’s more or less clear who will win and who will lose, but the victory condition hasn’t triggered yet. Then the losing player(s) may feel obligated to play out their part, but without any choices that can meaningfully improve their position, and perhaps feeling the temptation to take actions to make their position worse to hasten the end of the game. This is rarely a fun situation, and I think not just because it sucks to lose but because you have no actions that seem aligned with the values of the game – you have no choices that seem like “good moves” and you’re even considering choices contrary to the formal values of the game (such as trying to lose). Either way it seems like you’re not engaging in agency within the values frame of the game in the way that you are during normal, fun play.

What’s the record for skipping?

Mechanics that cause players to have their opportunities for action to be skipped, such as “lose a turn” mechanics or being on the receiving end of “denial” strategies, are commonly experienced as un-fun. It’s often recommended that game designers use these types of mechanics judiciously or even avoid them altogether. There’s a clear connection between situations of this type and experiencing a loss of agency.

Grief, briefly

In a previous post I gave the example of “griefing” as something that can erode the local values frame of a game by signaling that not all the players value the established values.

Thematic / Mechanical Tension

I had a lot of positive experiences playing the Marvel Heroic RPG, but one thing that came up a few times was that for some characters it was more mechanically effective to just do a straightforward attack than doing something more elaborate and comics-appropriate. Because The Thing had godlike strength it made more sense to just punch something every round than to use a round to grab a boulder or telephone pole to smash a bad guy with – doing that would give you bonus dice you could feed into a future action, but because the dice The Thing brings to pretty much any attack are already so good the bonus dice from the prop wouldn’t make much difference, so why bother? Similarly, Dr. Strange seemed like he was supposed to spend rounds building up power with his alliterative incantations for a big, flashy payoff when he actually completes the spell, but because you could use the same mechanic you would use for the buildup maneuver for a direct effect by just describing it differently it always felt like making an intentionally less-effective choice to lean into the more “magical” vibe and not just play him like he dishes out energy blasts. Having to choose between what seemed comics-appropriate and what made mechanical sense wasn’t fun, it was a choice but it felt like choosing which value to undermine, not exercising agency within the frame.

What game are we playing?

If I’m playing an RPG and I find that a rule or element that I thought was important is being ignored or handwaved by the other players or GM then the fun leaks out of play for me, especially if I had made decisions based on that understanding (for example, maybe I had used character options assuming a particular subsystem would be used strictly, but in practice it’s a mushier “rule of cool” kind of situation, or maybe I thought I had cleverly solved a mystery only to discover the GM is using a “whatever theory they propose is correct” technique, or I discover that what I thought had been a clutch die roll turns out to have been against a fudged target). For me this “fun leaking out” phenomenon seems to map to the magic circle I thought I was in being pulled out from under me. In situations like this it’s sometimes possible for me to start having fun again if I can get back on the same page as the other players, which I think maps to stepping into a different magic circle.

Open Questions

These examples are suggestive to me that there’s something fruitful about considering the values and agency elements with respect to working out game design problems, but there’s a potential “confirmation bias” problem in that it’s easier to think of examples that make sense than ones that don’t. Are there examples of un-fun gameplay that don’t seem aligned with this theory? Are there situations that this theory would predict are un-fun that actually are fun in practice? Can this theory be used prospectively to help design games or diagnose design problems, or is it only amenable to after-the-fact just-so stories? Games often involve trading different elements against each other (like the risk/reward tradeoff in a push-your-luck mechanic), how is that different from the thematic/mechanical tension I flagged as an example of a problem?

What are my options?

It seems to me that the perception of agency relates to the variety of choices/actions that are open to a participant in a game. But that’s also impacted by how those participants evaluate the potential actions open to them – it’s often said that expert chess players “don’t even see” the bad moves they could make. And evaluation relates to the values participants are operating with and how they perceive them, so agency and the local values frame of the game interact in a complex way. Questions related to how potential actions coalesce out of the perception of the current state seems like a core issue of game design, especially for tabletop roleplaying design where we want “the fiction” to be a meaningful part of that process. (In a microcosm/macrocosm way, that “how do we go from perception to identifying potential actions?” thing also seems like a core issue in living life, creating art, etc.)

[1] I’m going to sidestep the issue of “necessary and sufficient conditions” style definitions because I question how useful they are. Here I’m focusing on how games mainly work, not trying to explore weird edge cases.

[2] Like C. Thi Nguyen does in Games: Agency as Art, I’m also going to duck the question of trying to define “agency”, let’s just say I’m using it in the normal sense of the word.