What About What It’s About?

(cross-posted from my Substack)

What About What It’s About?

Thinking about how communication is nested in hierarchies, but also isn’t

When we communicate we don’t just communicate the content of our communication, we’re also communicating about those things. This sentence that you’re reading right now contains a particular idea, but it’s also communicating that it’s a written communication (which you can see by looking at it and recognizing that they’re letters rather than random squiggles), and that it’s written in English (which you can see by recognizing English words and sentence structure). This is why codebreaking and decryption are sometimes possible: if you send enough encrypted information through a channel someone could be able to figure out how to decrypt it, when you send encrypted messages you’re implicitly sending information about your encryption along with your message.

Also, think about tuning an old-school radio: in one sense you set the dial to a particular frequency so you can hear what’s being broadcast, but in practice what you do is get the knob in the right ballpark but then make fine adjustments until you can clearly hear some voice or music: you use the intelligibility of the audio to figure out the exact frequency-settings that they’re broadcasting on. Recognizing what language I’m using is kind of the same thing: you try to read the sequence of letters in the language you suspect I’m using, and if what I’m saying makes sense you conclude you’ve picked the right one. So in some ways the information is hierarchical: the sentence is within the language that I’m writing in. But in some ways it’s all just information: You need to understand what language I’m writing in to parse my sentences, but once you’re locked in on what I’m saying I can drop in some phrases from another language to add some je ne sais quoi and that communicates something, too. Or think back to the radio: if you know what audio signal the transmitter is supposed to be sending then you can detect deviations from that in what you receive when your radio is tuned to a particular frequency – so in principle you and the person sending the signal could use subtle variations in how they’re broadcasting to surreptitiously send information, in a way treating the “audio signal” as the carrier and the “radio frequency” as the communication channel.

Expanding the picture

Things like which language you’re speaking or whether you’re communicating via text or audio are relatively crisp distinctions, but I think it makes sense to think of fuzzier layers both up and down the scale. So in addition to the language that I’m speaking, and that I’m speaking, it’s also I that am doing the speaking – this may be why it feels validating when the specific things you say are heard and understood by others, it’s an acknowledgment of you as a person. And in the other direction, the specific things we’re saying are happening in contexts: you can have very low-level things like who the antecedent of a pronoun is, or what “former” and “latter” refer to, but there’s also the topic we’re discussing (maybe it’s a technical topic where some words have a specific jargon meaning), there’s the relationship between us, there’s the connotations of the words we choose to use, etc. There are communicative nuances up and down this pyramid-that’s-also-flat. We can expand or change the topic based on the particular thing one of us just said, or use a significant look to communicate something different than we could in words.

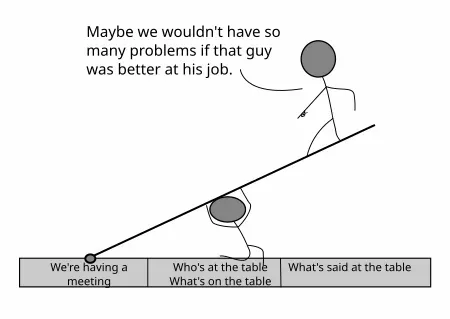

Sometimes these nested layers impact each other. In a negotiation, the meta-negotiation about who gets to sit at the table and what topics are on the table can influence the ultimate agreement (true for both literal and metaphorical negotiations). Doing things on one level can be a powerful way to shape certain interactions on another, but using high-leverage techniques has consequences. You can feel the tensions manifesting with the “elephant in the room” phenomenon, where people believe that a topic needs to be discussed but feel it’s not a topic that’s allowed to be raised. Sometimes things which are ostensibly happening within a context seem like they’re “really about” having an impact at a different layer. For example, consider a business meeting where people might be making “power moves” or “playing status games” rather than merely interacting in a way that’s solely about the topic of the meeting. A person with lower or unclear social status may feel intimidated to speak up against something said by a high-status person, thus reifying the status relationship between them. And sometimes people manipulate this dynamic intentionally by making statements or taking positions that others may not be confident enough to contest, demonstrating that they have the power to herd elephants into or out of the room and implicitly making a claim to high status. As another example, someone could intentionally raise a surprise topic they know is delicate for another participant, implicitly manipulating things at the “who’s at the table / what’s on the table” level even though it’s ostensibly happening within the conversation happening around the table.

Of course it’s not always about intentional maneuvers or aggressive posturing, communication is imperfect and people can do things unintentionally. Maybe I thought the conversation was going to be about one thing and you thought it was going to be about another, and one or both of us might be disappointed (or pleasantly surprised?) when we discover what it’s “really about” while it’s happening. And communication is not always about things which are explicitly communicative: we say that actions speak louder than words, we advise writers to “show, don’t tell” us about characters by the actions they take, etc.

What does this have to do with actual games?

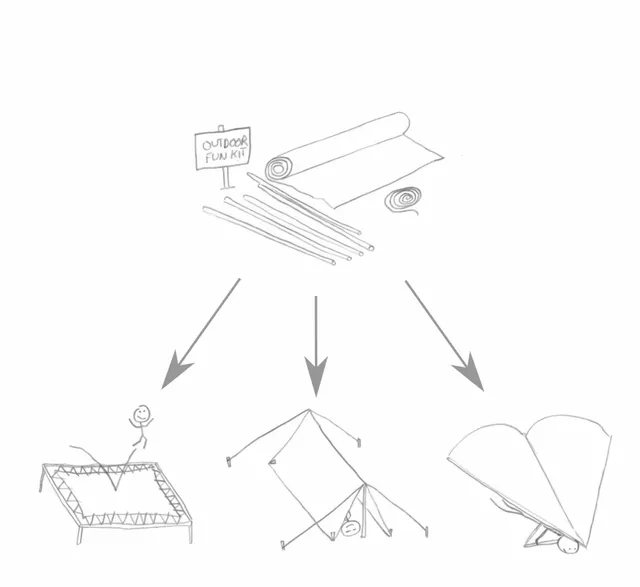

Gameplay happens in a context, what I’ve called a “local values frame”. Like in any human interaction there is the possibility of other layers being a factor. Consider the classic playground maneuver of deploying the threat “I can take my bat and my ball and go home” to influence contested rulings in a baseball game – the game can only happen in the presence of the equipment, so an outside-the-game considerations of who owns what can influence the inside-the-game consideration of whether a player was safe on base or tagged out.

In his book The Grasshopper: Games, Life, and Utopia, philosopher Bernard Suits has the Grasshopper character present the following fanciful thought experiment to his dialog partner Skepticus:

My account of lusory attitude is intended to rule out not ‘professional’ players of games, but the following kind of quasi-game player. Smith arrives at the starting line of the 200 metre finals just as the race is about to begin. He has only that moment learned that a time bomb has been planted in the grandstand at the finish line (which is located on the other side of the oval track at a point directly opposite the starting line), and that it will go off in a matter of seconds. The information has so shocked Smith that he is temporarily bereft of speech and so cannot warn anyone of the impending catastrophe. His first impulse is to run straight across the infield and defuse the bomb, but he sees with dismay that the infield has been fenced off with a high chain-link barrier, evidently to protect spectators and participants from the fifty or so man-eating tigers that roam hungrily inside the enclosure. At the instant Smith realizes that his only hope of getting to the bomb in time is to make a half circuit of the track, the starting gun is fired, and Smith and the other entrants are off and running hard.

Now, I put it to you, Skepticus, that the other runners are playing a game but that Smith is not, and that this is so because the other runners have lusory attitude and Smith does not.

The point is to show that things which look like actions which are appropriate to a game[1] may actually not be part of playing that game because the “player” wasn’t taking them in the context of being involved with the game (what I call operating within the local values frame of the game).

Sometimes actions that are technically legal within a game’s context nevertheless undermine a game. Consider the phenomenon of griefing, where a player uses in-game actions not to advance goals, pursue victory, or something else aligned with the local values of the game but to cause distress to other players. For example, in a competitive multiplayer videogame, one player in a position dominant enough that they could win by triggering the victory condition might instead choose to take other actions that extend the round while taunting or ridiculing an opponent. A player on the receiving end of this behavior not only experiences the unpleasantness of being taunted or ridiculed, they are seeing another player sending the signal “winning is not important”, even though caring about victory was something all players supposedly did when they stepped into the magic circle of a competitive game. By having doubt cast on one of the pillars supporting the context of play, the player experiencing griefing may feel they’ve been “knocked out of” the mindset of play, or feel the game has fallen out from under them. They may ask questions like “what are we even doing here?” when they see evidence that a value that had been guiding their game actions is not a shared value and the meaningfulness of their own previous in-game actions is called into question. The griefer’s actions have an effect at the “local values frame context” level, not just the “what’s happening in the game” level.

And it doesn’t always have to be intentional. One of the ideas that The Forge was exploring (in its own weird, internet-poisoned way) was that different players could both be making good-faith efforts to play a game but nevertheless be doing things that were incompatible with each other, resulting in an un-fun experience. A common way that humans learn about systems is to look at various parts and have an “aha!” moment of seeing how the pieces fit together. In something as complex as a tabletop RPG it’s possible for some people to see the collection of parts fitting together one way, other people seeing them fit together another, but not realize that “the way” that they’ve seen isn’t the same as “the way” that the other person saw. Then when they try to play together they can end up doing things at cross purposes.

Zooming back out

In my view, life, art, and gameplay tend to have microcosm/macrocosm relationships to each other. Just like games can have the gamespace be undermined by eroding the values that support it, we can see the same things in other areas of life (Do we care about doing a high-quality job, or are we supposed to have a “what can we get away with?” attitude? Do we care about what’s true about political issues, or is bullshitting OK because winning is so important?). If other people are ignoring a value it can be difficult to maintain it against a tide of social proof washing it away. Building things up tends to be harder than knocking them down, so establishing a value from inside can be tricky, especially if other people genuinely don’t realize it’s a thing that might be worth caring about.

I think this model of thinking has a lot of applications to lots of different things, so I found it hard to keep this post from expanding out to multiple different topics. I hope to write more soon about agency, local values frames, motivation, choice identification, economies, TTRPG discourse, Forge Narrativism/Story Now, and game moves as instances of self-expression.

[1] This thought experiment uses a footrace as an example of a game. Some people might balk at the notion of a race being a game – I don’t think a race is a typical game, but I think it’s a minimal game and therefore convenient to use in thought experiments since it is so simple.