My refugee story: how we escaped a brutal Marxist regime

My favorite personal finance podcaster, Joshua Sheats, briefly heard about my refugee story in a Facebook exchange related to his recent episode on financial planning for refugees. He asked me to expand on the story since he found it be interesting. My friends have always loved hearing this story, so I hope this post will be interesting for my readers.

My father's life story is so incredible that I have a hard time leaving out a lot of his background in this post. So I will do my best to generalize how my family ended up in the situation we got into in Ethiopia. I promise to write more stories about my parents in the future. I like to think it'll keep you all entertained.

My father, Semunegus Hailemariam, was born in 1935 in Ethiopia, the same year the Italian Army under Benito Mussolini invaded the country as revenge for their embarrassing defeat in 1896. They succeeded, using mustard gas against lightly armed Ethiopian forces, breaking League of Nations treaties. My grandfather, Hailemariam Woldemariam, died during the war by stepping on a mine when my father was three years old, while my grandmother later died from tuberculosis after the war ended. My father was only five years old when his mother died. He was then raised in a veteran's orphanage school and eventually found his way to an Oklahoma missionary farm in the Ethiopian countryside where he worked and lived as a farmhand. The family took such a liking to him that they formally educated him, enabling him to earn a correspondence high school degree and a scholarship to Oklahoma State University in the late 1950s. He later earned his PhD in 1965 from Michigan State in horticulture, with a focus on coffee. I am not doing his journey any justice by condensing it to a paragraph but I feel it is important to understand where my father came from.

Now let's fast forward to 1966-1974. After finishing his PhD, my father married my mother, Tsega Berecket, also from Ethiopia at the time (her birth city is now located in present-day Eritrea). She completed her Master's Degree in Biology at Oregon State University. Instead of staying in the US, my parents decided to move back to Ethiopia as the economy was improving and they were able to obtain great jobs in the government (father) and university (my mother was a biology professor). The Ethiopian monarch at that time, Emperor Haile Selassie, was mostly a free-market progressive but had started to lose control over his growing opposition. In 1974, the emperor was deposed and eventually killed by a brutal officer in the army by the name of Mengistu Hailemariam. Mengistu was responsible for at least a million deaths during his reign from 1974 to 1991 and was responsible for the Red Terror in the late 1970s when he decided to turn the country into Communism. He's listed as one of the ten "worst dictators" of all time.

When the coup-de-tat occurred, many political dissidents were jailed, openly killed or "disappeared". My father stayed out of trouble by remaining quiet while his friends were rounded up and killed for speaking up (lots of snitching, informants and secret police stings). My father was also the lead horticulture export/import expert for the government. Fortunately, his position was more of a scientist/adviser, so he stayed unnoticed by the Communist Party through the transition.

I was born in 1977 during the worst year of the country's Red Terror campaign. My three older sisters, who were seven, nine and thirteen years old at the time, remember seeing dead bodies on the side of the street with placards on them with words that read "traitor" or "anti-revolution". In order to plan our exit in the early 1980s, my mother was able to get a graduate scholarship at North Carolina State University to study microbiology. My parents' plan was to get my mother and all the kids to America where we could eventually request political asylum from a Communist country. Then my father would follow later on an international business trip to Europe and seek asylum in the US once he could get find a way to get there. Remember that the US has mostly been open to accepting political refugees escaping Communist countries, even to this day (e.g. Cuba).

When it was time for my mother to take all of us kids abroad with her, the head Ethiopian government officer in charge of external travel told my father that I would have to stay back but my mother and sisters could go. My parents could not fight back or appeal without raising suspicion that they were slowly escaping the regime. But my father knew the reason: the bureaucrat knew that my father would never leave Ethiopia without me and I was kept back to make sure my father stayed. I was a kind of collateral. Good thing I didn't know any better at my age.

So in 1982, my mother and sisters left. My father worked 11-12 hour days making sure his superiors were happy. We were fortunate enough to have a full-time live-in caretaker for me. So from 1982-1985, I was without most of my family, being raised by a very sweet nanny. I was always well fed and went to a good school. When I did see my father it was only for 30-60 minutes a day. I appreciated every minute of interaction with him but I also held back a lot of sadness and longing for my mother. I felt a lot of resentment in my heart because, at that age, I couldn't fully process why I was so alone. From age 5 to 7, I cried myself to sleep alone every night, begging for my family. Little did I know at the time what my father was going through after my mother and sisters had left in 1982.

During those years, my father had great success in his job. He was the lone bright spot in the Ministry of Agriculture. Because of the bureaucracy, most people spent their time writing useless reports but my father was able to build a valuable coffee export agency that sent goods to countries in Europe. This was sorely needed for the government because they could get access to hard currencies like the German Mark.

The dictator, Mengistu, who was a cold-blooded control freak, would regularly remove and personally kill people with his sidearm pistol. Sometimes he would do this in the middle of a meeting. The victims were usually higher level government workers he considered incompetent or annoying. He encouraged subordinates of high-level supervisors to snitch on their bosses. It was normal for employees to get their boss killed. If you were accused of being bourgeoisie by your employees, there would be a quick hearing by a judge and usually, a quick execution would occur by firing squad. My father had two agency farmworkers that decided to bring up charges against him of being anti-proletariat in the early 1980s while my mother and sisters were still in Ethiopia. My father faced the judge but the accusers did not cover up their lies very well and were instead found to be lying themselves (my father later told me that no one ever got out of this court alive). My father was given the choice of having them executed or letting them go. He chose to let them go because he felt his Christian faith required that he forgive them, but it was the first personal sign that we needed to get out.

In 1984, the dictator noticed my father's great accomplishments. One of the dictator's staff members did a quick background investigation and discovered my father never formally joined the Communist Party, which was, of course, a requirement for every government worker. This aroused a lot of suspicion in the dictator's inner circle and my father claimed it was only a clerical mistake or oversight. He never heard any more about it and in fact, no one ever asked him to formally join the party. This concerned my father but he kept quiet. Aside: it turned out to be a blessing that he never joined the party because he would not have later received asylum in the US. If he had formally started the process of joining the party, the repercussions would have been worse as it would have raised more red flags.

One day, my father was told that the dictator would personally join him on a previously scheduled trip to a coffee farm. My father suspected that the Community Party snafu attracted Mengistu to him. The dictator traveled in his own caravan with 5-6 decoy vehicles since there was an active civil war against his regime. During the visit, the dictator lavished praise on my father in front of all his staff and security officers. He also started insisting in meetings that the Agricultural Minister's staff need to get their act together and be more like my father. The dictator began asking my father for his personal advice on agricultural policy. He joined my father on 3-4 additional trips.

The Minister of Agriculture was a close friend of my father's since childhood. He noticed the attention and told my father that whenever the dictator started praising (or rebuking) people, they always ended up dead. It turns out being close to the dictator was a death sentence. Time after time, the pattern was that the dictator would bring someone closer and closer to his inner circle with praise and kind words, then would inevitably find a mistake that the person committed (e.g. talk out of order or not meet an impossible deadline) and have them summarily executed or disappeared.

My father knew he had to get us both out of the country. Asking the bureaucrat in charge of citizens leaving the country to let me out could be a death sentence without good reason. My father had befriended an Italian medical doctor during his travels to Rome. This doctor wrote a note stating that I was gravely sick and needed immediate medical attention in Rome. I don't remember what the purported ailment was but I was not actually sick. This was a huge gamble by my father, but he knew the end was near and had to go forward. Miraculously, the bureaucrat approved my travel with no questions. My father later told me that the trust he had built up was key in getting this approval. My father was on state television once a week reporting agricultural output numbers (communist TV is not intended to entertain) so he had built up a lot of trust with everyone in the country.

One morning in spring 1985, I woke up to my father strongly nudging me awake from my sleep with the words, "we're going to see your mother and sisters, get up now!" I had never jumped out of the bed so quickly. He had already packed our belongings in two suitcases with all our travel documents and most precious family pictures. I quickly put my clothes on, got in the car with my father, met my father's best friend at the airport, and they waved us goodbye.

We flew to Rome and two months later obtained a visitation visa from the US embassy there to go to America (there's a long story here too). The rest is history. My father's other childhood friend took care of the cars and our house in Ethiopia for decades. For many years afterward, the dictator kept asking about my father and when he was going to return. Miraculously, the government never confiscated his property and we have been able to keep it to this day. But my father heard later from his Minister friend and from other close friends, that his days were numbered and it was only a matter of time before soldiers yanked him away in the middle of the night. We left literally just in time.

My father's hard work and dedication building the coffee industry from the ground up in Ethiopia and the loyalty/trust he built throughout the years was what eventually saved him. He later got a good position in the United Nations, Food and Agricultural Organization because of this experience. This, in turn, allowed all of us to get a great college education in the US and live comfortably along the way. Unfortunately, while we were living in the US, he worked overseas alone in places like Vietnam (a hardship post in the 1980s) and Bangladesh, making sure his salary supported us.

It's only as an adult and especially as a father that I truly appreciated what my parents did for us. The kind of sacrifices they made for us was unbelievable. Sometimes I complain about something dumb like my iPhone's battery life, then remember where I came from and gain instant perspective.

Stay tuned as I fill you in a lot more details over the coming months.

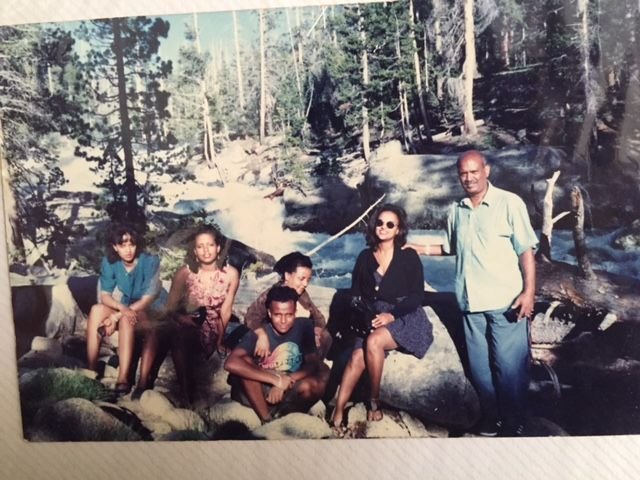

Our family vacation at Yosemite Park. The best memory I have of my family together (1990 or 1991).

Congratulations @hilawe! You received a personal award!

Click here to view your Board

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Congratulations @hilawe! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!