The Man Who Hawked The Cosmos

Stephen Hawking never won the Nobel.

How apt. That is evidence that it is difficult to put value — in terms of a Nobel — to his intelligence and contribution to science.

But there’s another side to it. True that his black hole radiation theory is revolutionary, but science demands evidence. Quite possible that technology to test the theory will be available in the near future. Didn’t Peter Higgs have to wait for over 50 years for the Higgs-Boson theory to be proved. It took a century to find observational evidence for Einstein’s theory of gravitational waves in space.

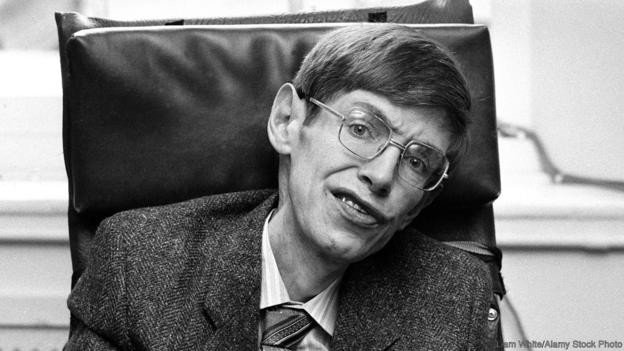

Hawking the cosmologist, theoretical physicist, specialist in general relativity and quantum gravity, was modest, if anything, about himself: I was never top of the class at school, but my classmates must have seen potential in me, because my nickname was ‘Einstein.’

A quietly funny man who liked Superman — he’s everything I am not, he used to say, referring to Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) that paralysed him gradually.

He lived his cosmic dreams, becoming the first man with ALS to “fly” in Vomit Comet, a reduced gravity aircraft, to experience weightlessness.

In the early 1960s, doctors gave him just a couple of years to live; the ALS was worsening they said. In 2017, he celebrated his 75th birthday. That’s relativity for you!

How does one assess a person such as Hawking? Or talk about his legacy? Phew! I am not going there at all.

I’d rather touch on a particular aspect of the great man which I found engaging. In 2010, Hawking collaborated with American theoretical physicist, Leonard Mlodinow, on a book titled, “The Grand Design”. The work startled his admirers and critics alike, for here was the Black Hole theorist and quantum gravity specialist talking about not physics but metaphysics, not about science but about philosophy.

Ah! The scientific world sighed. Is it true that at the point science ends comes belief? For, Hawking noted in the book: “Because there is a law such as gravity, the Universe can and will create itself from nothing. Spontaneous creation is the reason there is something rather than nothing, why the Universe exists, why we exist.”

Till the book’s release, the world knew Hawking to be a no-nonsense scientist. An atheist to boot. He once famously said: “One can’t prove that God doesn’t exist, but science makes God unnecessary.” He had always found religion inferior to science in answering the world’s puzzles.

Asked once if there was ever a possibility of science reconciling with God, he answered: “One does not have to appeal to God to set the initial conditions for the creation of the universe, but if one does He would have to act through the laws of physics.”

What, then, convinced Hawking to take to metaphysics?

Till the book’s release, the world knew Hawking to be a no-nonsense scientist. An atheist to boot. He once famously said: “One can’t prove that God doesn’t exist, but science makes God unnecessary.” He had always found religion inferior to science in answering the world’s puzzles.

Asked once if there was ever a possibility of science reconciling with God, he answered: “One does not have to appeal to God to set the initial conditions for the creation of the universe, but if one does He would have to act through the laws of physics.”

Where physics ends is metaphysics, I suppose. Metaphysics, to put it simply, is a concept that says that to be is to be something; that nothing just exists. We have had the Greeks, from Socrates to Aristotle via Plato, ruminate on this long before the current era began. A crucial work on the subject is in “Phaedo”, Plato’s fourth and last Dialogue that focuses on the immortality of the soul.

Hawking himself never convincingly talked about it. In 2011, a year after the book came out, he told a television channel during a show: “We are each free to believe what we want and it is my view that the simplest explanation is there is no God. No one created the universe and no one directs our fate. This leads me to a profound realisation. There is probably no heaven, and no afterlife either. We have this one life to appreciate the grand design of the universe, and for that, I am extremely grateful.”

You should read the book. Quite interesting for the kind of questions it throws up. Science. Post-science. Physics. Thermodynamics. God. Energy. Fact. Belief. Different kinds of adversarial atoms thrown into a Hadron Collider for a philosophical conflict on science conducted at the speed of light.

I would have loved to talk to Hawking about all this. What was there before the universe began? If there was nothing, then nothing must have been something for it to create the universe, isn’t it? Alternately, before the point of beginning of the universe, was there nothing? Both science and philosophy answer these questions with their separate sets of evidence.

Let us take Hawking’s assumption about the universe coming out of nothing a bit further. Can nothing create anything? Or, what is it that makes nothing create something, like the universe? Are we crossing the threshold of science and fact and entering the world of belief and God? I don’t know. Hawking did not clarify his statement subsequently.

Was he posing a metaphysical or even a philosophical question that is beyond the pale of science? Does science convert scientists into philosophers after a point? Oh, God!

Until another Hawking comes along, we won’t know the answers.