SPACE-TIME CURVES ENVIRONMENT TO THE OBSERVER

Everywhere it is repeated and expressed again and again, that space-time is curved in the presence of mass and that the curvature of this creates gravity. For this article poses in a surprising way that space-time actually curves even in the presence of only one observer still without mass, that is to say, that bodies in front of an observer follow a relatively curved space trajectory. In this article, we explain in this order of ideas, the reason why space-time is curved around the mass as an observer. We present as one of the apparently too extraordinary and conclusive proofs that space-time is curved in the presence of the observer, we describe after it in this article, a transcendental demonstration of the relativistic Doppler effect. It would be too interesting if the pupils of any physicist, however, concentrated or deconcentrated they are for any reason, are concerned with this description of the relativistic Doppler described by means of the curvature of spacetime for the observer.

1 Introduction

Space-time is the geometric entity in which all the physical events of the Universe are developed, according to the theory of relativity and other physical theories. The most "straight" possible lines of a space-time are called geodesic lines that are lines of minimal curvature. The name refers to the need to consider the geometric location in time and space in a unified way since the difference between spatial and temporal components is relative according to the state of movement of the observer. In this way, we speak the space-time continuum.

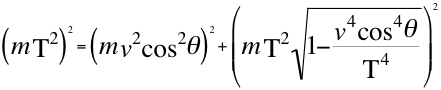

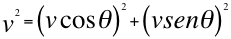

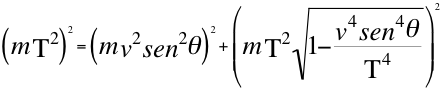

Here we also remember in this introduction that in the following way it was also expressed in the article gravitational tachyon, a relation that describes with respect to the component vcosθ the behavior of a particle that moves away from the observer:

Where m is the amount of invariant mass of the particle that is observed moving away, T is the speed of the taquión, v is the speed of the particle in the space-time, θ is the angle described between the trajectory of the particle and the observer.

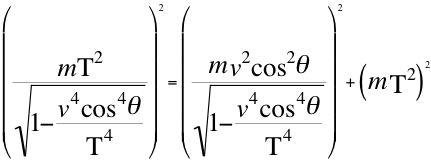

Now we detail a relation that describes the movement of a particle that approaches the observer with respect to the component vcosθ:

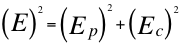

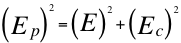

These two previous equations number one (1) and two (2) we can express it in the following way in function that if of the invariant energy E, the kinetic energy Ec and the gravitational potential energy Ep:

(3)

(3) (4)

(4)Where E is the amount of invariant energy of the particle that is observed moving away or approaching the observer, Ec is the relative kinetic energy of the particle that moves away or approaches the observer and Ep is the relative gravitational potential energy of the particle that is moving away or approaches the observer.

The invariant energy with respect to the tachyon velocity E = mT2 of a particle is constant and is equivalent in energy to the invariant mass of the particle:

Where E is the invariant energy of the particle, m is the invariant mass of the particle and T is the tachyon velocity.

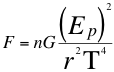

We start by saying that in Newton's gravitational relationship we can express it in terms of the gravitational potential energy Ep:

Where F is the force of mutual attraction, n is a scalar that defines the relation of the invariant energies of the objects, Ep is the gravitational potential energy of the observed object, G is the universal gravitation constant, T is the tachyon velocity, r is the distance that separates the centers of gravity of both objects.

2 Development of the Theme.

At the beginning of the development of this article, it is pertinent to clarify that, the concept of "observer" that we are going to use in this work, is that system simultaneously sensitive to both the electromagnetic manifestations of the observed particle and the gravitational manifestations of its object that is observed.

In a general relativity, the energy-moment relationship of a particle that moves in space-time would be those two equations that would relate to a given observer, the relative components of energy-moment vector related to the mass at rest, of the respective particle that correspondingly moves with respect to that observer.

When a particle moves away or approaches an observer in any direction and senses its velocity v, it can be decomposed into two components perpendicular to each other described with respect to the angle of observation: Avcosθ component useful for the study of relativistic Doppler, a component that it will be located externally or internally in the same radial or straight line of sight that has the line segment that joins the respective particle with the relevant observer, and another component vsenθ that will always remain totally tangential to the imaginary circle around the observer and will be perpendicular to the aforementioned line of previous vision.

WHEN A PARTICLE IS REMOVED FROM THE OBSERVER

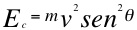

We will refer to the case first when a particle moves away from the observer, then the vcosθ component of the velocity, on the other hand, will describe its kinetic energy mv2cos2θ, it will be in the external direction to the same radial line of vision or visual direction that precisely joins the particle with the observer, that component will be directly directed away from the observer at an angle of 180 degrees and will be external to the imaginary curvature around the observer.

The component vsenθ on the other hand, will be moving away also but relatively and minimally in one of the two directions totally tangential and exterior also to the imaginary curvature of spacetime that circumscribes the observer and will also be perpendicular to the previous line of vision of that observer, it will be parallel even with the same origin of the vector Ec = mv2sen2θ of the tangential and relative kinetic energy for that observer. That component will be moving away in a direction that describes an angle of 90 degrees with respect to the observer.

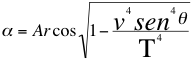

The vector Ep of the orthogonal gravitational potential energy appears with respect to the tangential velocity vsenθ relative to the observer, which we will immediately remember immediately for this observer in the following relation number eight (8):

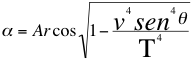

Where α is the open angle to the observer described between the gravitational potential energy Ep and the resulting invariant energy E of the observed particle moving away.

WHEN A PARTICLE COMES TO THE OBSERVER

We are going to refer now secondly to the case when a particle, is now studied by an observer who approaches that particle then, that component vcosθ of the speed on one side located part of the internal radial line of vision or visual direction that precisely joins the particle with the respective observer, will be in this case is directed directly looking at the observer and will have the same direction, sense and point of application that the gravitational potential energy Ep of the particle described with respect to the speed tangential in the previous relation number nine (9). This vector vcosθ will be circumscribed and completely internal to the imaginary circle of curvature around the observer. That component vcosθ, in this case, will describe an angle of zero degrees with respect to the observer.

The other component vsenθ for its other side for that observer, will be and remain totally perpendicular to the line of vision described above, will be of direction and tangential sense and totally outside the imaginary curvature of spacetime around that observer by which will definitely move away from the observer and will be parallel to the outside and with the same point of application as the tangential kinetic energy vector also outside and relative to the observer Ec = mv2sen2θ. This vector vsenθ and Ec = mv2sen2θ, in this case, will definitely move away from the observer. It is worth noting that even though the particle approaches the observer, the tangential component vsenθ moves away. This component, in this case, will also continue to describe an angle of 90 degrees with respect to the observer.

The fourth vector of time with respect to vsenθ, as the vsenθ of the particle tangentially moves away from the observer will then describe, a vector directed towards the observer of the gravitational potential energy Ep of the particle, perpendicular to the vector of the relative tangential kinetic energy and of its vector sum then precisely will result, the invariant energy E of the moving particle:

It is worth noting that despite the fact that the vector Ep of the gravitational potential energy of the particle approaching the observer is a vector totally directed towards the respective observer, it remains one of the two components of the resulting E vector of the invariant energy that describes an angle α with the gravitational potential energy, supremely insignificant almost zero degrees and open towards the observer equal to that described when the particle moves away:

As any physical quantity that is a function of velocity, the kinetic energy and the total energy-momentum relation of an object, not only depend on the internal nature of that object, they also depend on both the internal nature of the observer and the deep relationship between the object and the determined observer, therefore they can not be independent of it as apparently it is intended to understand Einstein in current physics.

So far we have described the analysis of observers that by their internal nature are unable to collapse the wave function. It can be seen that when a particle moves away from the observer, the two components of the velocity also move away, leaving both of them completely outside the imaginary circle of the curvature of space-time around the observer, but it does not happen when a particle is described approaching the observer. , the two components that constitute the velocity, one of them is tangential and contrarily also moves away relatively to some extent from the observer, being totally outside the imaginary circle around the curvature of the space-time around the observer, the other component comes directly to the observer and stays within the imaginary curvature around the observer.