Between Cuba and Harvard, an uncommon garden

In the summer of 1899, Boston sugar magnate Edwin F. Atkins and Harvard professors George L. Goodale and Oakes Ames gathered in a busy sugar mill in Cienfuegos, Cuba, for a meeting that led to the establishment of one of the world’s richest tropical gardens.

The meeting took place at Atkins’ sugar estate, where the Harvard Botanic Station for Tropical Research and Sugarcane Investigation/Atkins Institution in Cuba would be created a few years later. It unfolded against the backdrop of the Spanish-American War and emerging U.S. imperialism.

It’s a story that has fascinated science historian Leida Fernandez-Prieto, who was born in Cuba and works as a researcher at the Madrid-based Spanish National Research Council’s Institute of History. She came to Harvard in the spring to research the history of the garden as the Wilbur Marvin Visiting Scholar of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Affairs.

“The three men behind the garden were visionaries,” she said. “One was a businessman and the other two were driven by scientific ambition, but their collaboration enabled the garden to flourish.”

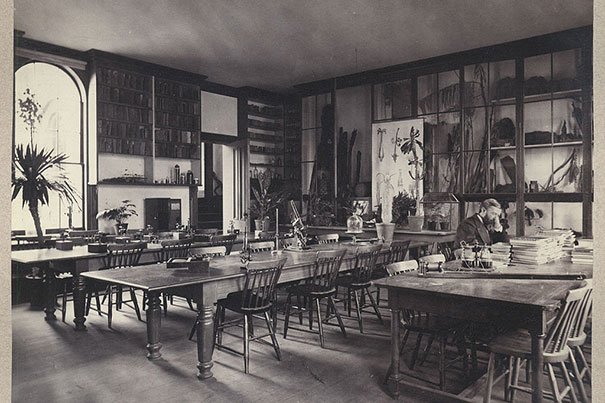

*Harvard Professor George Lincoln Goodale in his laboratory at the Harvard Herbaria. © President and Fellows of Harvard College/Arnold Arboretum Archives

Atkins provided resources and land and funded labor costs for Harvard scientists to develop sugar cane resistant to plagues and diseases, but before long researchers had turned the garden into a lab, planting trees from all over the world. By the early 20th century, the Harvard Botanic Garden was considered the center of tropical research in the Western Hemisphere.

Now called the Cienfuegos Botanical Garden and managed by the Cuban government, the site is home to more than 2,000 species of tropical plants, including different breeds of palm trees, bamboos, figs, and orchids. Its 280 species of palms make up one of the world’s largest collections.

The history of the garden has political dimensions, and includes slavery, conspiracies, and revolution, said Fernandez-Prieto, who has been working on the subject for the past three years. Atkins bought sugar plantations in Cuba in the early 1880s and was likely involved in slave labor until the practice was abolished on the island in 1886.

After the Cuban war for independence, the garden continued to grow, and in 1920, it officially became part of the University. But in 1961, in the wake of the Castro revolution, Harvard’s operation of the garden was suspended.

*Harvard University Laboratory palm trunk, taken in 2000. © President and Fellows of Harvard College/Arnold Arboretum Archives

“What I’d like people to see is that this is a fascinating story of scientific discoveries, political tensions, and a world of intrigues,” said Fernandez-Prieto.

The work of a science historian is similar to that of a detective, she said. Fernandez-Prieto met with former Massachusetts Rep. Chester Atkins, the magnate’s great-grandson, and spent many days digging in the archives of the Massachusetts Historical Society and the Arnold Arboretum, which house letters and documents linked to the garden’s administration.

Over the past decade, Harvard has been making efforts to renew ties with the Cienfuegos Botanical Garden. In 1999, a delegation of academics traveled to Cienfuegos to celebrate its 100th anniversary. And in recent years, students have spent the summer doing research in the garden.

The 222-acre garden attracts thousands of tourists every year, as well as botanists, zoologists, and biologists from all over the world. Fernandez-Prieto hopes renewed U.S.-Cuba relations help bolster scientific exchange between the nations.

“The garden was very important for the relationship between Cuba and the United States,” she said. “After so many years of not working together, I think the botanic garden could be a bridge between the two because it’s a common heritage. It’s part of the history of both countries.”

I upvoted You

Hi! This post has a Flesch-Kincaid grade level of 13.7 and reading ease of 39%. This puts the writing level on par with academic journals.