How to Refute Fermi’s Paradox by John Robb

Will we survive the future? Can we navigate a path through the existential risks that kill advanced civilizations?

Based on Fermi’s paradox, it doesn’t look good for human beings.

However, if there was a way to disprove Fermi’s Paradox our odds of surviving the future will become very good indeed. The Fermi paradox goes like this:

There are an estimated 10 billion terrestrial style planets in our galaxy alone and our galaxy is proving to be fecund (full of the building blocks of life). if this is true, we should see lots of evidence of alien civilizations. Needless to say, we haven’t. That’s the paradox.

By extension, this suggests that our potential to survive the future is nearly nil since no other advanced civilization has. Pretty grim, unless it can be refuted.

So far, there have been many attempts to refute the paradox, but none of these provide a quantifiable mechanism for doing so.

One way to do this might be found in Arthur C. Clarke’s famous quote:

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

Essentially, this insight provides us with a clue to drawing quantifiable information out of Fermi’s paradox.

Translated to our needs: What if we when we look at the stars for signs of advanced civilizations, we don’t recognize their technological artifacts and perceived advanced behaviors for what they are?

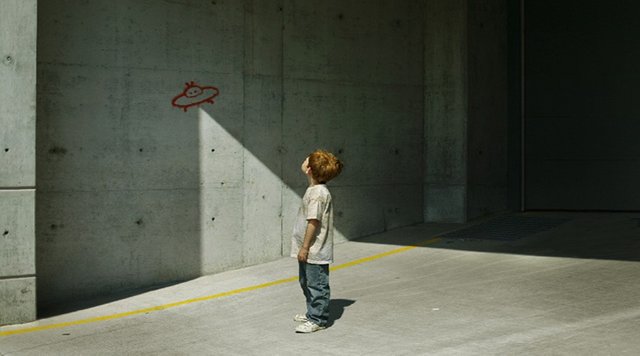

For example: a tribesman standing in a field 1,000 years ago might see a modern aircraft flying overhead as a magical or godlike bird.

This insight becomes even more useful if we take it to the next level:

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from nature.

In other words, what if we couldn’t even see it at all? What if we simply lack the cognitive, perceptual, and developmental frameworks necessary to even view it as something other than nature (~the white noise of the universe).

For example: an early human standing in a field 500,000 years ago would see a plane as a big bird or simply not see it all.

What does this mean?

This means that although we can look back at less intelligent life, our ability to look forward to view more intelligent life is very limited even with advanced tools of observation/analysis and creative insight.

In many ways, this is similar to the way a two dimensional being perceives a three dimensional being in two dimensional space. It sees only a small fraction of the three dimensional being, and what it does see, looks like a two dimensional object. To get a good feel for this, quick purchase ($0.99) and read Edwin Abbott’s very short and amazingly insightful classic “Flatland.”

The layers of dimensionality used in Flatland suggests a way to turn this perceptual limitation into something quantifiable that we can use. It suggests that as human beings have developed, from a single celled organism to the global species we see today, we have made many advances that would unrecognizable to the previous versions of ourselves.

Assuming this is true, how many perceptual jumps have we made?

To answer this, let’s focus our attentions on the last 10 m years. From the earliest apes to the humanity of today. Within this time frame, let’s divide into five we’ve big jumps (roughly measured) that if seen at a distance would be invisible to the earlier version of humans. For the purposes of this analysis these jump can be VERY roughly approximated.

5m years: the group behavior of the early hominids

3.5m years: to the earliest stone tools

1.5m years: fire

200k years: tribal/group memory (200 k)

10k years: modern civilization.

What this does show us is that the perceptual window for looking forward is shortening at an accelerating pace. This means that an intelligence just tens of thousands of years ahead of us may be completely invisible to us.

It also provides us with some amazing insight into the Fermi paradox. Let’s work through this:

Assuming perceptual filters, we can only see other intelligences that are within the 10,000 to 20,000 year window of our current level of advancement.

Let’s assume intelligent life may have developed in our local, observable area up to 1 billion years ago (it’s likely much larger than this).

The potential of overlap? 20,000 years out of 1,000,000,000 across a very limited subset of planets (what we can directly observe).

The conclusion? There’s a nearly zero percent chance of perceptual overlap. The fact we don’t see any other intelligence in the universe tells us nothing about whether we are alone or not, nor does it tell us anything about whether we will survive into the future or not.

John Robb

PS: This suggests that if we do find “basic” life on Mars or close by, don’t get depressed. It doesn’t imply that we won’t survive. All it shows is that we live in a fecund universe.

https://medium.com/@johnrobb/can-we-even-see-alien-intelligence-67ddbc888f9d

wellcome

Hi! I am a content-detection robot. This post is to help manual curators; I have NOT flagged you.

Here is similar content:

https://medium.com/@johnrobb/can-we-even-see-alien-intelligence-67ddbc888f9d

easy cheetah, easy @anyx you might be interested in this content

brought to you by -6 rep guy, you are welcome

Nice article

Thank you Dude

Hi! This post has a Flesch-Kincaid grade level of 8.9 and reading ease of 66%. This puts the writing level on par with Leo Tolstoy and David Foster Wallace.

thank you Isaac, whiskey?