Get off my ground ! Territories, fights, and spiders

In ecology, we do want to answer a lot of unnecessary questions: like how did a squid become dependent on a bioluminescent bacteria? what do frogs say when they sing? Etc. etc.

Let’s talk about territories and fights in the animal kingdom! Of course, these behaviors are much diversified, so I will just discuss some aspects in some spiders that defend the nest they built. Why those spiders build such nests? Why and how do they fight for it? Because we all, every single day, wonder about it, I will use this lovely example to illustrate some territorial behaviors, ecological approaches and questions about it. 😉

Territoriality in animals

Territoriality is a form of space-related dominance that arises from resource competition, such as food and water, mates to reproduce or shelters to defend their offspring. Dominant animals would have a better survival and more offspring. Then, if the gains of having a territory outweigh the costs of defending it, territorial individuals will be advantaged, and this trait will be selected for.

Animals have developed various behaviors associated with their territories, including nest construction! Males can build nest to attract females, as their breeding territories often reflect their quality, used as criteria for females’ choice (intersexual competition). On the other hand, females can benefit from territoriality to feed and protect their descendants.

These constructions demand important investments! We therefore expect them to be valuable resources, just as you wouldn’t build a house to give it up to the first person asking it. Any owner would prevent conspecifics from taking over their own place. If you had no way to lock your apartment with all your precious things, you would need to guard it -or to pay somebody to do so, so it is super costly (in energy and time for animals).

Territorial individuals would often exclude any conspecific intruder from this area by different advertisements and threats. If it fails, the host would be forced to abandon this place and its investment in it. Would they be ready to fight for it?

Game theory and fighting strategies

When encountering rivals, one can display weapons or ornaments. Fighting is often ritualized and can only be about displaying the biggest ornaments, or it can come to real fighting.

Individuals make choices: do I want to fight this lady that just doubled me in the line?

following decision rules, that form strategies: I was waiting before, it is my right to do so.

and that can be either fixed or adjustable: alright for this time, she is much older, I just can't do it.

Rivals can follow the same or a different strategy. Each strategy has benefits and costs, that can change according to the rival’s behavior. The best strategies can be naturally selected, based on their economics (the benefits/cost balance).

Let’s come back to our territory behaviors: both the territory owner and the intruder follow their own strategy. In this case, we often use the game theory to describe the fight and predict the advantageous behavior to follow.

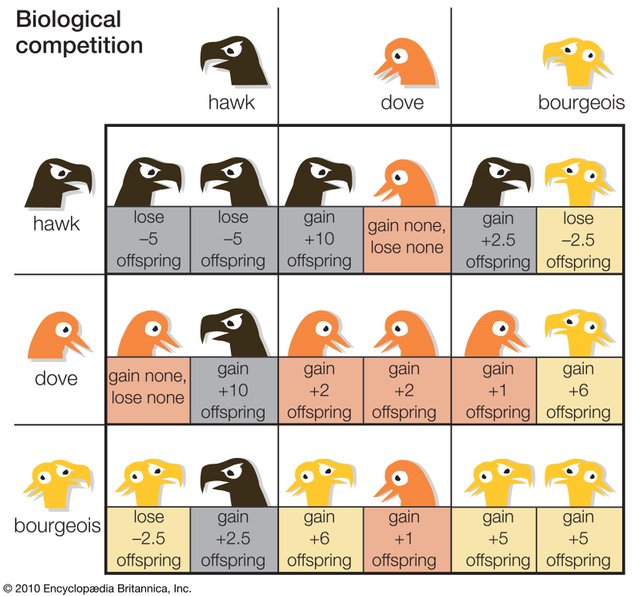

In ecology, the game theory can be explained using three examples of strategies.

A hawk would always fight whatever the rival’s strategy, until the latter retreat or the hawk gets injured.

A dove would always display first and retreat if the opponent escalates.

Therefore, a dove would always retreat in front of a hawk. This costs the dove and benefits the hawk. Two hawks would hurt each other, gaining few or nothing, while two doves would just have limited benefits.

What is the best strategy to follow? It depends on the cost of fighting and the values of the resources. A big hawk can fight a smaller one, but he wouldn’t do so for something he isn’t interested in.

Adapting your behavior can also be a smart move. A ‘bourgeois’ individual would play hawk if it owns the resource but would prefer to retreat if not. In terms of territory, all intruders would actually retreat while owners would keep their space, by doing… nothing.

This last strategy would maximize the cost/benefits balance and therefore be stable in front of hawk and dove strategies.

There are plenty of potential strategies, and contenders could adjust their strategies based on their previous experiences. Then, we often talk about the ‘winner effect’: if you won, you’re more likely to win the next one (and vice versa).

So… Is it really worth fighting?

Contenders need to assess if the situation is worth fighting so they can adjust their behavior, following their own strategy. Then, following the game theory, animals would only fight over a valuable enough resource, with a reasonable cost of protecting or gaining it.

Contests over resources are often asymmetrical in three ways.

Information access: is this spot really good? The holder knows more about the territory’s value, knowing the benefits of winning the fight. Still, if the intruder can evaluate the benefits, he can choose to fight or flee.

Investment: the owner spider probably spent days building that web, the intruder did nothing. The holder has more to lose.

So, owners should doggedly defend their territory (it is the ‘resident effect’). Then owners would follow a bourgeois strategy.

- But it also depends on both fighting abilities: which contender is the stronger? Here, we often assume the bigger the stronger.

How do animal contenders know whether they should give it a shot? We imagine two possibilities: either the contender decides to give up because he reached his limits, or he is capable of assessing the other's abilities and know he stand a chance (self or mutual assessment).

In the example of a territory, an intruder could assess the resident’s strengths (weapons, body size) through sensory signals (e.g. acoustic, visual, olfactory, or vibratory), allowing him to adjust its behavior.

The marvelous Agelena spiders

I did some field work on the funnel-web spider Agelena labyrinthica. Look at this beauty:

You can find plenty of them everywhere in France. This spider is territorial: both males and females build web-nests on the ground or vegetation.

Once mature, males leave their own nest, to find a female in her nest and guard it. Males often fight while guarding; by defending the territory, they protect the access to the female and maximize their chance to reproduce with her.

Females do not leave their nests and rely on them to predate, find a mate, and protect their offspring. It is therefore a highly valuable resource and its construction is an important investment (of time, energy, and resources). A wandering female would be please to find a fully-prepared nest while a spider who built it should really don’t want to lose it.

Do females fight for their nest? Is it random? If not, what strategy do they follow? Do residents always win (bourgeois strategy)?

I expected them to defend their nest by actively fighting intruders, except if they could assess the intruder is much bigger. I basically spent hours in the German forests, looking for females in their nest. I captured females, measured and marked them (the color dots on the pictures), and took them away from their own nests. I then introduced them on another occupied nest (each tested only once), and I noted everything happening to see who would win, and why. I also checked there was no ‘capture effect’, to see if manipulating individuals would lower their chances of winning, by capturing, measuring and marking nest owners either before or after the fight.

What is their fighting strategy?

Both behaviors and fight outcomes showed they follow a bourgeois strategy: the intruder most often flee without even chasing or attacking the resident. Still, this strategy is not rigid. Some bold intruders did try to take over the nest. I found a positive size effect: very few bigger intruders succeeded to steal the nest, and although residents do not systematically attack, they clearly do when the intruder is much smaller. It seems logical, right? But if a behavior has a strong genetic basis, which can be the case for it to be transmitted to the descendance, it wouldn’t be that much adaptive. More, this shows that spiders do know how the other one is and are able of assessing their winning chance.

Indeed, these web spiders evaluate the other during a pre-contact phase. We all have seen cute spiders moving their pedipalps around and tapping their web: that’s their way of communicating. And in a fighting contest, they assess the fight economics through both self- and mutual-assessment, using these signals on the web. Both intruder and resident feel the other moving on the web and wrestling their pedipalps.

I leave you with a video illustration of all these behaviors I filmed on Agelena labyrinthica. Enjoy some of the contests and the beauty of these skilled spiders!

*All pictures without stated credits are mine.

Some references:

Alcock J. 2001. Animal behavior: An evolutionary approach. Seventh Edition.

Arnott G. and Elwood R. W. 2008. Information gathering and decision making about resource value in animal contests. - Anim. Behav. 76: 529–542

Arnott G. and Elwood R. W. 2009. Assessment of fighting ability in animal contests. - Anim. Behav. 77:991–1004

Keil P. L. and Watson P. J. 2010. Assessment of self, opponent and resource during male-male contests in the sierra dome spider, Neriene litigiosa: Linyphiidae. - Anim. Behav. 80: 809–820.

Maynard Smith J. 1989. Did Darwin get it right? Essays on games, sex and evolution.

+quoted references in the figures