Our Social Skills in a Post-lockdown Melbourne: Part 2 - Why I decided to Write and Publish

As I sit on my bed and attempt to write, I’m motivated by fear. The fear of losing parts of my brain that are unrecoverable. I want to know, no, need to know, if the parts of my brain that are switching off can ever be turned back on again. Can I relearn the skills I’m gradually losing, or will it take years to regain what I’ve lost?

I’m fearful because I can feel it happening, and I’m watch it happening in others.

In the Art of Manliness’ podcast interview with neuroscientist Daniel Levitin about his book Successful Aging, he explains that interaction with other humans, namely conversing, is one of the most complicated activities we can do. And no, phone calls and Zoom sessions don’t count. With this in mind, it makes sense that if we stop doing this massively complicated activity each day like we used to, we’re going to get worse at it.

If we don’t use it, we lose it, right?

Well let’s see.

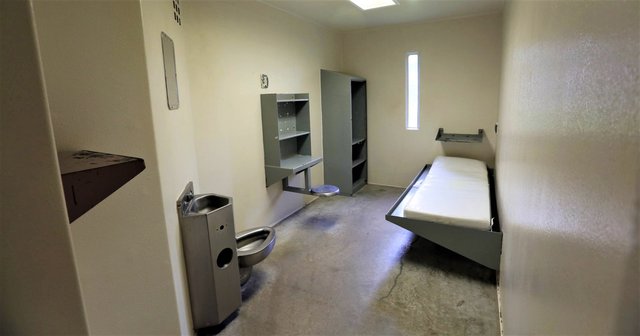

It may seem drastic to compare strict lockdowns to solitary confinement, common as a form of punishment in the United States.

The Oxford Dictionary defines Solitary confinement as this:

The isolation of a prisoner in a separate cell as a punishment.

In other words, a person is physically isolated with minimal interaction with other people.

The mental health toll on those who have endured solitary confinement are extensive, but there are several symptoms that jump out at me that could have a massive impact on social skills. Namely:

- Emotional flatness

- Issues with attention, concentration, and memory

- Easily disorientated, and confused thought processes

- Social withdrawal and loss of social initiation

- Hostility and Irritability

- Impulse control issues

- Depersonalisation

- Fear of death

- Paranoia

(Sourcebook on Solitary Confinement by Sharon Shalev, page 16.)

For me, this list was depressing to say the least. I could easily see glimpses of these symptoms in the people around me who had endured the long, drawn-out process of lockdowns here. I know for myself, I’m slipping further and further into social withdrawal and often find myself disorientated whenever I step out of my apartment building or am faced with a question I wasn’t prepared for. This affects my work and my side-job as a podcaster.

I’ve also witnessed a growing lack of empathy from some of my friends as lockdown persists. And, coupled with social withdrawal even after lockdown ends, it’s uncertain how long it will take for that empathy for others to return, if ever.

Craig Haney, PhD, APA member and professor of psychology at University of California, Santa Cruz says "One of the very serious psychological consequences of solitary confinement is that it renders many people incapable of living anywhere else… They actually get to the point where they become frightened of other human beings".

This particular comparison may seem drastic, but it is pertinent in light of COVID-19 and the fear, uncertainty and doubt surrounding us today. As an extreme example, my husband’s colleague uses Reddit as his single source of news during this pandemic, and has become unbelievably convinced that COVID has a near-100% death rate. Misinformed, sure. But also maybe… paranoia?

I lay down a challenge now, dear reader, to look at yourself and the people around you to see if the symptoms of solitary confinement now look familiar to you. Solitary confinement is a form of torture for a reason. No one leaves it unaffected.

I decided to write and publish because the more people who can realise how lockdown has affected them, the more people can work towards getting better. If you don't know anything is broken, then you don't know it needs fixing.

Healed people can help heal others.

My next post will dig into the possible bad news about how the lockdown has affected our brains. But don't worry, it will be followed up by a post about the good news.