Passion in Practice

Little Black Dots

In the beginning of your book Shakespeare on Toast, you confess your earliest encounters with Shakespeare in school didn't make much of an impression... so I’m curious, what led you to wholeheartedly dive into this work?

It was definitely through acting it. Plenty of other times and places I’ve talked about how it didn't make any sense when I read it in school, but then all of a sudden when I was in front of an audience acting it, I discovered the missing piece of the puzzle, as it were.

Over the years this epiphany has coalesced into something much bigger, including my love for helping younglings to not have the same experience that I did in school. Through it all I've realized the expectation that anyone could really gain a deep appreciation or understanding of Shakespeare simply through reading it in isolation is... extremely difficult, to say the least.

It reminds me of something the magician Teller (from Penn and Teller) said when he put together a production of Macbeth in California and DC a few years back—he said, ‘no one other than a master conductor should be able to look at the black dots on a score and be able to tell you what the tune is; no one other than a master chef should be able to look at the ingredients of a recipe and tell you what it tastes like... so why should someone be able to pick up a Shakespeare play, and imagine the entire scene unfolding before them?'

This led me to understand that these plays were not only written for an audience to watch, but were also written for an incredibly experienced and tight body of men —only men because that was the tradition of the time— who were singularly trained and skilled in the craft of performing. These actors spent upwards of 340 days a year in the same building together, getting to intimately know each other, the building, and a regularly returning audience, coming back every day, expecting the same troupe to perform a new and different play every time.

Given this vast experience, and the deep understanding and knowledge they possessed, these actors would have known so intimately their master’s voice. And because about 80% of Elizabethans couldn’t read, and only half of Shakespeare's works were printed in his lifetime, this means that only they (the actors) would have actually been reading these plays.

So in a way Shakespeare was originally a kind of oral storytelling tradition?

In a way, yes. For example, the actor who would play all of the clown parts would have copied out his lines from the main prompt copy as cue scripts, and kept hold of these scripts. Only he alone would have possessed them, and for some of the plays that hadn’t been printed in Shakespeare’s lifetime, the editors would have gone back to these actors to get those parts, to rebuild the plays.

So as an actor, you would’ve been the owner of your part, and also the owner of the skill sets needed to unlock those parts. And so now we’re looking at a Shakespeare play and realizing that each particular part and character was actually carefully built and written for one particular actor.

If you’d have taken one of the plays in its entirety as we have them now and shown it to an Elizabethan actor, it would have been like showing a synesthetic a kaleidoscope of many different sensory inputs... it wouldn’t have made any sense, because no one would have received them in this way. And even if someone was able to make any traction with it, it'd be because they would’ve had far beyond the 10,000 hours we talk about nowadays that's needed to become a master of a craft.

Yet these are the things we hand over to kids in school and say ‘stand up, read it out loud.’ And they have no idea what the little black dots mean... and why should they?

So my journey into Shakespeare started with bafflement, reached a point of suddenly waking up to a taste of what it could be like, and then over the last 10 or 15 years, with various points of guidance —whether from practitioners, directors or academics— I’ve been trying to uncover a way back towards understanding these things directly.

ORIGINS

Is there a particular name for this reconstructive approach to Shakespeare?

A lot of this work falls under the classification of what are called 'Original Practices'. There are numerous original practice crafts, such as the way we use the space, or making costumes as close as we can understand Elizabethan costumes to have been, or sword fighting and stage fighting, or make up and music. And there are also original practice theatres, such as the Globe Theatre in London, and the Blackfriars Playhouse in Staunton, Virginia.

And the point is—how does a piece of clothing, for example, or the spatial dynamic of the theatre space, restrict or aid our movement around the stage, and how does that change and inform the way we perform and produce these works? Does this mean we should only be wearing Elizabethan costume, or can that exploration be the catalyst for guiding the next 25 years of production?

A lot of folk use the term Original Practices, but approach them like a buffet, picking and choosing different combinations of original practices, to greater or worser effect.

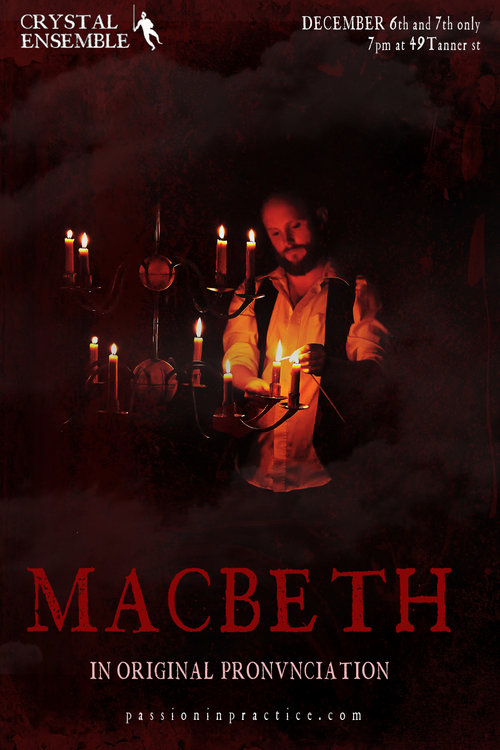

Then there's what we've started calling Original Pronunciation, or OP, which is the study and practice of the original accents that Shakespeare and his actors spoke in. This is basically a reconstruction of the sound system of Jacobethan London... and by sound system, I mean right now apart from a few dialectic and regional differences, you and I are speaking the same language—we just use a slightly different sound system to access it.

And to be more precise, OP is specifically a reconstruction of the language of Shakespeare’s own theatre and works, which we've devised by studying various historical resources. These include things such as the dictionaries of linguists writing on pronunciation in the early 1600’s, Shakespeare's own spelling, the spellings of the compositors of his printed works, and the reconstruction of his rhyme schemes (which often don’t work anymore when spoken with a Modern English accent). By drawing from these resources, we feel we're able to get the accent about 90% right.

When listening to OP, I find myself resonating with the verse in a more visceral, earthy kind of way...

Many people say that... in part I suppose it's because every now and then you hear wynde instead of wind, or fahwr-tune instead of fortune—these sort of unexpected aural pokes in the ribs that are unlike anything found in Modern English accents. I imagine it's similar to playing older folk instruments, where even though you aren't playing extra notes (in most cases), you get different acoustics and overtones; sounds that are perceived as engaging and enlivening to our modern ears.

That's a good analogy, and many traditional folk musicians also draw from past musical and performance practices to enrich their crafts... as an actor, how do you approach utilizing these practices in a way that feels authentic and relevant today?

Well, of course I’m never going to be an Elizabethan actor in Elizabethan London... and thank god because I’ve got all my teeth! But the Original Practices are not about the search for an exact replication of the past, because when you're looking to reconstruct an authentic experience, it will never be exactly ‘authentic’ to what came before—it will only be close to it... so for me the point is not to try and recreate the experience as if you were traveling back in time, but rather what can you learn from doing it as close to the original as possible, and then using that as a springboard from which to leap?

And as you mentioned in the epiphany you had, I imagine the context of the audience (which is a very different audience today than it would have been in the past) plays an important role in defining this process as well.

Absolutely. Anybody that's been in the run of a show for a long period of time will tell you that when you're rehearsing for a play, there's this tipping point —especially when you're doing something like comedy— where things that were funny in the first couple of takes stop being so... and live performance is when the audience will actually teach you where the laughs are; they will teach you the rhythm of a piece, in a way that you can't discover without them.

That experience I had when I was 17 or 18 —performing Shakespeare and realizing for the first time the audience had been the missing dynamic— was actually only half of the revelation. Because in that first experience of acting Shakespeare in front of an audience, I realized ‘ahhh ok, the audience is there, and they’re laughing and responding, and now the play is starting to work properly’. I finally understood a Shakespeare play in terms of its performance potential. But at that time I still couldn’t see the people watching me, and hadn't yet realized how useful that contact could be.

Then I got to the Globe, and realized I was supposed to see them; that these plays were built for a two-way dynamic. Because if you feel like I’m talking to you, and I feel like you’re listening directly to me, then we journey together, and you’re more likely to laugh if I make a joke when I’m Hamlet, and more likely to cry when I die. This revelation completely transformed the idea of receiving Shakespeare 'in context' for me.

It made me realize that's it—that's the comedy/tragedy mask, that's what we're trying to do... to make you laugh and make you cry, make you think and send you home; make you call your mum.

But when they turned the lights off in the theatre 150 years ago, suddenly we all started sitting quietly, and the audience became less of an active presence. Of course this provoked a very interesting turn of direction for plays and playwrights —indeed, there are many parts of the theatrical canon of plays that don’t work with the lights on, and there are certainly huge theatres that don’t work or look very nice when you turn their lights on, and sets that would seem plain when not beautifully lit— but in Shakespeare, the audience is such an integral part of the works, and its their imagination that's supposed to light the stage.

HEARTBEAT AND HEARTBREAK

Beyond the Original Practices, what other resources can help make Shakespeare's writings more accessible to audiences and readers?

I've found one of the central ingredients to understanding Shakespeare is recognizing the way in which he utilizes iambic pentameter in his verse—and this doesn't mean simply understanding that he wrote in this thing called iambic pentameter, and that the rhythm of it goes de-dum de-dum de-dum de-dum de-dum... but to realize he was using and manipulating this poetic device to show his actors, as someone else once said: 'the heartbeat and the heartbreak.'

Meaning, in Shakespeare the rhythm of the poetry is essentially the pulse; the heartbeat of the character. And even though we don’t have any direct anecdotes to affirm the methods the actors may have had in Shakespeare’s time, it really can’t be coincidence—as soon as you look under the hood at the mechanics of any speech, the breaks and a-rhythms in the metre always seem to chime with a particularly strong or meaningful line for the character. In a way they represent the music —as in the written score— underneath the words.

Rhythm in poetry is known as metre; poetry with a steady, regular rhythm is known as metrical poetry. Here's a classic example of such a thing:

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

(Sonnet 18, opening line)

A line of poetry with ten rhythmically ordered syllables is a line of pentameter. In Greek, iamb means a weak syllable followed by a strong (de-dum). A naturally iambic word is com-pare.

Some say that putting the stress on the non-standard part of a word makes you sound like you're new to the language: say the word feather and stress the -er instead of the feath-. It'll sound odd, maybe a bit like someone from France speaking English for the first time: feath-er.

We know that the opening line from Sonnet 18 has ten syllables in it, so it's a line of pentameter. We know that the word compare is pronounced iambically, so we can assume the rest of the line is iambically stressed too:

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

(de-dum de-dum de-dum de-dum de-dum)

That's quite a structured framework within which to write, and as a result working in that steady metrical rhythm can impose certain things on your writing. It can make you invent new words to fit the rhythm, and it can make you shorten or lengthen words.

Vasty is a good example of how Shakespeare invented a new word so as not to upset the flow of the metre.

Can this cockpit hold the vast-y fields of France?

The rhythm bounces along nicely. He could have used vast in its original form:

Can this cockpit hold the vast fields of France?

But with the two strong stresses together, the rhythm stumbles.

The opposite of this is to remove a syllable and make a contraction — shortering a word to fit the metre. For example, the first line and a half of a speech from Macbeth (Act 1, Scene 7, lines 1-2), marked up, could be read like this:

If it were done when 'tis done, then 'twere well

It were done quickly.

The first line wants the attention: it's a healthy line of ten syllables. If Shakespeare hadn't contacted it is and it were (making 'tis and 'twere), it would be a line of twelve syllables.

Shakespeare wanted this a regular line of pentameter — though as you can see from the mark-up, despite the contractions helping to stress the important words like done, well and quickly, it's still not evenly stressed. Why? Perhaps because the two sequences of weak syllables (when 'tis and the second It were) add pace to the lines — an appropriate effect for someone talking about being in a hurry.

An uneven yet regular line of metre, for a man who is becoming fairly uneven himself, and who is only a scene away from hallucinating with a dagger . . .

If Shakespeare had wanted Macbeth to come onstage and speak slowly and carefully, he'd have written:

If it were done when it is done, then it were well

Much more measured and controlled. Contraction brings speed: it makes characters speak faster than they would do if they were spelling out every syllable — a note for the actor, that the character is speaking (and so therefore thinking) quickly or is excited.

Of course, when you direct an actor, there's more to it than 'which words do you stress'. Sometimes you might want to tell them when to move, where to move to, who to stand close to. Perhaps, if you're feeling particularly inventive in your capacity as a director, you might want to start directing the emotions that the text requires your actors to act out.

[Through manipulating the rules and form of iambic pentameter], Shakespeare found a way not only to tell his actors which words to stress, but all the other things too.

In Toast I compare Shakespeare's verse to the improvisations of the great jazz musician Miles Davis. Like Davis, when Shakespeare was searching for this a-rhythmic quality that would make his verse sound more like natural speech, like any great improvisor he wouldn't just play around all the time, because then the verse loses it’s anchor. Instead, he would always return to that regular rhythm, to remind us of what he was improvising from. So for Shakespeare, iambic pentameter is that rhythm.

In addition to this element of rhythm, I found it fascinating to read in your book how Shakespeare utilized the spectrum of prose and poetry as an expressive device in his works... can you say a bit about this?

Well generally speaking, when taking the two primary writing styles in Shakespeare —poetry and prose— as a character shifts from speaking in prose to poetry there’s often an increase in import and emotion, hand in hand with the increase in the heightened style. In part, this is because in poetry there’s more structure to the writing style and the speech style—again, it's like that heartbeat/heartbreak idea; it has to do with how fast the blood is flowing through you.

So if what you have to say is relatively easy, relatively pedestrian, relatively straightforward, then you can express yourself in prose. But the more you refine that structure into rhyming verse, or into the even more polished structure of sonnet —with alternating rhyme schemes, quatrains, couplets and what not— then the greater the import. Romeo and Juliet's first meeting, which has the structure of a sonnet, is Shakespeare telling us, not with the words he uses, but the way he uses them, that this is the most beautiful of first encounters.

Now the audience may not necessarily notice all of this in the performing of it —hopefully they wouldn’t, because they would be taken in by the moment— but the actors certainly would have. And because Shakespeare’s style of poetry was also the rhythm of spoken Early English, this allows his characters to sound heightened and natural at the same time; the everyday rhythm is bound into the poetic structure.

These elements uncover an incredible depth to Shakespeare's writing that one would almost never grasp without this greater context.

Yes and watching Shakespeare over the course of his twenty odd years of writing, as he understands his acting company, his audience, and the stories he chose to tell; as he discovered the possibilities that breaking the rules of the iambic pentameter could give him, and further watching him play with giving one particular type of character prose, and then dropping in a rhyming verse or a sonnet here or there, or giving Desdemona The Willow Song to suddenly sing shortly before her death... understanding the number of different ways he had at the tip of his quill to make his audience laugh, and to make them cry, and realizing indeed that if you do make them laugh, then they would often cry even harder shortly thereafter… it’s astonishing. It’s absolutely astonishing.

DISCOVERING ELOQUENCE

A question that people often ask me, and I probably asked when I was in school as well is: ‘since all Shakespeare is written as poetry, did everyone always speak in poetry back then?' And I had a realization just the other day that not only did they not speak in poetry all the time, but they actually spoke very much like we do.

Yet the main difference is that compared to today, in Shakespeare's time words were still relatively wondrous, strange, and magical things. To be able to write and sign your name beyond an X, to be able to read from a book or a letter was a skill few had, and those with it would often be sought out.There’s a character in Romeo and Juliet who’s sent to invite folk to a party, but can’t read who he has to invite... so to coin new words, as Shakespeare so often did, or use familiar words in new ways, must have sent electricity through the air above the audience’s heads.

It was also much more of a storytelling culture, because the finer dimensions of the arts—such as painting and classical music— were higher and further away from most people at that time, and the powers of speech were one of the few things that most could appreciate.

So what I’m coming around to is the heightened quality of the text—not only was it an uncommon way of speaking, but that experiencing such a beautiful, eloquent speech was pretty unusual too. It still is. Who comes to mind when you think of eloquent speakers today? Rhetoric isn't something we teach our younglings anymore.

Even Shakespeare's relatively beautiful (though unstructured) prose was experienced as heightened as well, because of the eloquence he put into his verse. This eloquence has partly to do with elements like preparation and theatricality and showmanship, but it’s also about how he crafted what he said—it's about rhetoric.

And then raising this prose up to poetry would’ve sounded almost symphonic; it would have sounded so utterly musical and spellbinding, because it would've been so far out of the norm.

Realizing this has made me have to rethink how I approach verse speaking, the effect it would have had on an audience at that time, and how rarely that effect seems to happen to people nowadays... people don’t seem to be electrified by heightened speech anymore.

Do you think that's because we've lost this type of relationship, this sensitivity to the nuances of human speech?

I think so. It's funny because today we often tell each other that we need to express ourselves, that we need to talk our problems out... but we don’t really teach anyone how to do that through the power of the voice—how to become sensitive to these finer points of rhetoric, allegory, rhythm, etc.

I realize now, through having to explain my approach to the craft of it all, that all these years I’ve simply been trying to make these tools of storytelling all the sharper.

CONTINUOUS RENEWAL

What are your next steps as an artist and an educator?

I’m not sure whether I feel like I’ve done the work I want to do on storytelling. Perhaps that’s where I’m moving towards next... I’ve certainly felt that people have been struggling with Shakespeare in my generation, and his work is still trying to find it’s feet in the early 21st century.

You often hear about how many generations of kids have been forced to study him, and have ended up hating him. If anything I hope I’ve helped with this a bit, because I don’t think the problem is ever really going to be solved until we’ve managed to completely redefine and redevelop what we believe an education system should look like.

I said not long ago that I hope in 20 odd years people may say, 'Ben Crystal, yeah he was close to getting it right, but this is how we should be doing it.' Because that’s what in some respects I’ve been doing—acting as a stepping stone or a bridge to the next bit.

That brings to mind a quote that I feel speaks to this, which is: ‘Tradition is continuous renewal’.

That’s brilliant. You know, very recently a friend of mine from Amsterdam passed away... I'd seen him a month before and he'd been perfectly chipper, but had been fighting cancer for a while, and as is the way sometimes, he suddenly went.

There was a big turn out for the service, and they had this nice sort of granite secular building in the graveyard. Afterwards we filed out through the doors to the grave, and as is sometimes the tradition, you had the opportunity to take a shovel and scatter a little bit of earth on it if you'd like, and so we did.

Then we went back to the building and had a glass of wine, and just as me and my friend Will were about to leave, we remembered his wife had some time ago gone back to the grave.

So Will and I walked back to meet her, and found that three or four of her friends had shovels between them, and were in a circle going round and round, taking turns filling up the grave with the big pile of sand that was next to it. Without really speaking or saying anything, Will and I just joined the circle, and literally actually buried a friend for the first time.

After a while we took a break, and at that moment Will began to speak a sonnet or two, that he felt resonated, like 'No longer mourn for me when I am dead', and blow me down if we didn’t keep shoveling until every last grain of sand was in there.

It was extraordinarily profound, and I’m still sort of dealing with it. It was a group of friends saying goodbye to their friend together, and actually burying him.

That’s beautiful... and I think exemplifies everything we've been talking about.

I know right? It was a real-life experience of an old way.

And also a new way, because without foresight you simply opened up and shared your inner resources in the moment.. and perhaps you wouldn’t have been able to express yourself in that way without your connection to the craft of Shakespeare.

For sure. You know, I think there’s a number of things we think Shakespeare probably should be, or that we want him to be, and although we certainly want him to be experienced in a way that's relevant for the next generation, I think it needs to be about more than that.

As much as the real art of Shakespeare is about learning how to speak well, and learning the old ways, it's also about teaching our younglings how to listen to their own hearts, to follow their passions, and trust their own deeper instincts within themselves.

www.BenCrystal.com & www.PassioninPractice.com