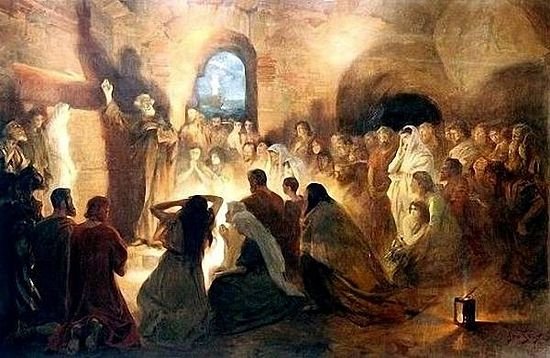

The Myth (part I): What is oral tradition?

Introduction

In this first part of a series of theoretical publications about the theme of the Myth we will focuse on the different concepts about the oral tradition, a cultural environment where many of the ideas about the principles of humanity and the moral principles of human society are registered and transmitted from generation to generation. The objective of this is to make a pertinent distinction between the three main narrative genres (tale, legend and myth) in order to expose a key concept about the topic of interest (the myth).

Definitions of Oral Tradition

The Oral Tradition has been one of the main topics of study in the Social Sciences since its foundation. Jurists, travelers and even compilers devoted their efforts in collecting and, very rarely, analyse the structure of the narratives that were transmitted in the primitive peoples and modern societies at certain times, although it was not until in recent years that social scientists as Montemayor (1996), Evia Cervantes (2007) and Vansina (1968) decided to define first what is this compendium of stories per se.

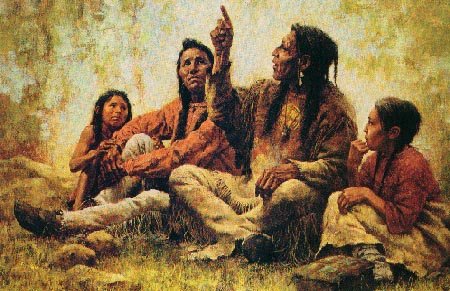

Montemayor states that the Oral Tradition is a language and cultural complex that must be explained from the "Art of the Language". The author points out that, in a strict sense, the oral tradition is an art of composition that has precise functions, particularly the preservation of ancestral knowledge through chants, prayers, incantations, discourses or stories. This not only reflects the changes that the indigenous cultures have been experienced during the Colonial period and after the latter, but also the persistence of the Prehispanic religious and artistic world (1996: 9 and 10).

On the other hand, Evia Cervantes states that Oral Tradition is a set of stories which are part of a group's collective memory that manifests itself in the communication between the members of a society or a specific community. The attribution of the traditional character is due to its contents, which are taken repeatedly expressions that were drawn up and transmitted by the members of previous generations to the present members of the society. The oral character, in the other hand, is due to the usual way of transmission which is the verbal.

This author also points out that there are five elements that conform Oral Tradition: Collective memory, Orality, Tradition, Plot and Interpretation. The collective memory is the permanence of the speech in one or several generations, which can be manifested individually or in group. This comes through the orality, that is the formulation of a verbal exchange between two subjects in order to pass the knowledge from generation to generation and give rise to the tradition by evoking memories of the past, which are produced in a place where there is a socially constructed order and is reinforced by repetition. Tradition gives place to the argument, called the plot, which builds the story that conveys the speaker, so that the listener can interpret or explain the elements basing on its function within the same (Evia Cervantes, 2007: 84 - 88).

Jan Vansina, meanwhile, denominated the Oral Tradition as an "Oral History" since it is a set of real testimonials about everything related to the past; they are historical sources whose own character is determined by the shape, being oral or not written. These oral sources have the peculiarity that they underpin from generation to generation in the memory of the men. However, the author makes an emphasis on the care that must be handled this definition, since not all oral sources are oral traditions in relation to the temporary space (1968: 13 and 33-34).

From this perspective, the emphasis is clearly relevant since not all oral traditions make reference to the past. Vansina mentions that the rumor and the testimonials are two examples that reflect this controversy: both are oral traditions, but both do not talk about the remote past (1968: 34).

A point in common that converges the three definitions is the generational knowledge transmission. Whether between relatives, friends or people who do not share ties of kinship among themselves, an ancestral knowledge is transferred through the narrative. Then, this can stimulate and regulate the socialization of the individual with its environment as well as the preservation of knowledge transmitted despite the changes to which it is subject with the pass of time.

.-.-.-.

Consulted sources

- Evia Cervantes, Carlos (2007) El mito de la serpiente Tsukán. Mérida, Yucatán, México: Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán.

- Montemayor, Carlos (1996) El cuento indígena de tradición oral. Notas sobre sus fuentes y clasificaciones. México. Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social (CIESAS) Oaxaca. Instituto Oaxaqueño de las Culturas (IOC).

- Vansina, Jan. (1968) La Tradición Oral. Barcelona: Labor.

.-.-.-.

Part II

.-.-.-.

Spanish version

.-.-.-.

GIF created by @fabiyamada

Good stuff. For the record, myth comes from the attic Greek "mythos", which simply means "story". All accounts of humans used to be stories, until the cult of Reason took over in the wake of the Enlightenment. Never was a movement more poorly misnamed ;-)

That's a good record, mate! Thank you :)

I fully support what Ken Kesey once said: We need fewer facts and more stories!!