Jean Francois Lyotard - The Postmodern Situation

Jean-François Lyotard is a French philosopher and literary theorist. Known for the post-modern artillery and the analysis of the postmodernity of the human situation. When talking about Lyotard, we must start from the sociological link between postmodern situation and postmodernism. In his post-modern work, Jean-Francois Lyotard tells us about the problems of postmodernism. He shows us that this science is a quest for instability, it is a resistance or a rift in modernism and denotes the state of culture after the transformations affecting science, literature and art from the end of the nineteenth century. What distinguishes postmodern theories is the negative attitude towards established canons. The "postmodern situation" is a testimony to the end of universalism and totalalizations, revealing on one hand the atomization of society and, on the other, the passage of state power into the hands of increasingly impersonal technology administration.

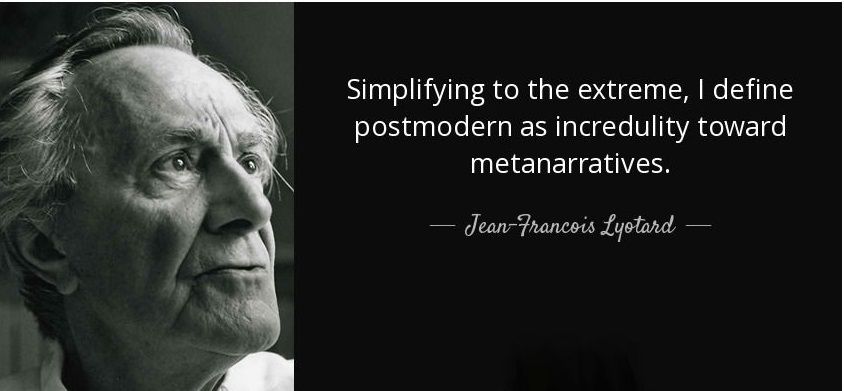

Lyotard believes that science has been in conflict with narratives since its origins, because according to the criteria they seem like fiction. Postmodern thinking requires proving the legitimacy of the prerequisites that determine knowledge and its language. According to Lyotard, scientific knowledge needs argument and proof, and "narrative" on the other hand is a denial of legitimacy. This is also the problem that Lyotard focuses on in his research. He says that we can accept "postmodern" as a distrust in meta-histories that is the consequence of the progress of science, and scientific knowledge is a kind of discourse. It is believed that the impact of technological transformations on knowledge is significant. Those two are the main functions of knowledge, they are research and the dissemination of knowledge, both of which are directly affected by the innovations. Increasing the number of information machines will increasingly affect knowledge as they are moving and exchangeable, as has previously been the case for transport and the media. In recent years, knowledge has become a major manufacturing force. According to Lyotard, the possession of knowledge will become a major dispute between states, and if they had fought for territories before, they could fight for knowledge. According to him, however, scientific knowledge does not exhaust all knowledge, it has always been in conflict and rivalry with another kind of knowledge, namely narrative knowledge. In order for a statement to be recognized by the scientific community, it must go through the legitimacy process - whether it is fit for internal sustainability and to verify the authenticity of the experience. Lyotard then discusses language games and makes three observations. The first is that the rules of the games do not contain their own legitimacy, but are established with the understanding between the players. The second is that there can be no play if there are no rules, and a small change in the rules changes the game itself. The third is that "every statement must be understood as a move made in a game.

The French philosopher is of the opinion that "we can not know knowledge ... if we do not know anything about the society in which it fits in. We can decide that the fundamental role of knowledge is to be an element of the functioning of society and to influence it, but this can happen if we accept knowledge as a great machine. Lyotard says that knowledge does not coincide with science, according to him, it is not limited to science or knowledge. Knowledge can be defined as a set of denotational or object-describing statements that differ from others and can be declared true or false. Science can be considered as a subdivision of knowledge. It is made up of devotional speeches, offering us two additional conditions for their acceptability: first, the objects to which they refer, are accessible recursively, under clear conditions of observation; and second, to be able to decide whether each of these statements belongs to the language that the experts consider appropriate. By the term knowledge, we do not understand a set of devotional speeches, including skills ideas, life experiences, the ability to listen, and so on. According to Lyotard, it can be said that the narrative in some respects is a typical form of knowledge.

On the other hand, scientific knowledge requires the differentiation of a linguistic game-denotation and the exclusion of all others. A criterion for the acceptability of a statement is its true value. The truth of the speech and competence of the subject of the speech depend on the agreement of members with equal competence. Within the research game, the required competence refers only to the post of the subject of the speech. A scientific statement draws no validity from something that has been rewritten. The scientific game requires diachronic timing, memory and project. The push of narrative play remains significant both among media users and within themselves. The language game of science seeks the truth about its speeches, but since it is unable to legitimize it through its own means, it uses the narrative. From the very beginning, the new language game poses a problem of its legitimacy. Scientific knowledge can not know and show that it is true knowledge, without resorting to the other knowledge - the story of ignorance. The way of legitimation that introduces the narrative as the validity of knowledge can take two strands depending on whether it represents the subject of the narrative as cognitive or practical: as a hero of knowledge or a hero of freedom. Lyotard pauses in two large versions of the narrative narrative, one of which is more politicized and the other more philosophical. "Subject of one version is mankind as a hero of freedom. All nations have the right to science. If the social subject is not yet a subject of scientific knowledge, it is because the priests and tyrants have interfered with him. The right to science must be gained again. This narrative requires a focused policy on initial training rather than universities and higher education. In the other story of legitimacy, the connection between science, the nation and the state allows for a completely different structure. At the founding of the Berlin University between 1807 and 1810 this became clear. The university has a significant impact on the organization of higher education in emerging countries. He makes his way the idea that the subject of knowledge is the people. Universities have to expose the knowledge base and reveal the principles and grounds of every meaning at the same time, because without a speculative spirit there is no creative and scientific capacity.

Scientific research and the dissemination of knowledge is not justified on a consumer principle and it is not considered that science should serve the interests of the state and / or civil society. The humanist principle that mankind becomes more worthy and freer through knowledge is neglected. "True knowledge always appears indirectly - it consists of rewritten and inserted statements - in the meta-analysis of the subject providing the legitimacy" 5 *. In the first version of legitimacy, knowledge does not find its validity in itself, in a subject that evolves, updating its cognitive abilities, and discovering it in such a practical subject as humanity. The people are guided by the freedom of self-governing self-determination. Knowledge has no other extreme legitimacy except to serve the goals identified by the practical subject as the autonomous collective. According to Lyotard, in contemporary society and culture the question of the legitimacy of knowledge is put in another way. The big story no longer trusted, no matter what kind of uniformity it is attributed to whether a speculative narrative or narrative about emancipation. The sunset of the stories can be seen as a consequence of the technical innovations after the Second World War, after which the emphasis was placed on the means of action. Lyotard writes that the embryos of "delegitimation" and nihilism inherent in the great 19th-century stories must first be mentioned.

A science that has not found its legitimacy, Lyotard points out as a false science and falls to the lowest level, namely at the level of an instrument of power or that of ideology. It turns out that the discourse that has to legitimize it stems from the scientific knowledge that does not differ from the "extra-popular" narrative. This could happen if the rules of the scientific game that he has already described as empirical turn against him. A scientific statement is knowledge only if it places itself in the universal process of being born. The crisis in scientific knowledge is not the result of accidental proliferation of sciences, but is probably a consequence of the progress of technology and the expansion of capitalism. It is due to internal erosion of the principle of the legitimacy of knowledge. The classical distinction of the different fields of science at the same time becomes the subject of rethinking: discipline disappears, raids are taking place within the boundaries of science where new territories are emerging. Universities are exempt from the responsibility of studying, betting on the transmission of accepted knowledge as safe, and thus providing production to predominantly scholars instead of scientists. The other legitimation procedure is the mechanism of emancipation. It concerns another aspect. It is characteristic for her that it serves as the basis for the legitimacy of science and truth through the interpersonal autonomy involved in ethical, social and political practice.

If this "clematism" continues and extends its reach, an important postmodern science will be discovered, namely that science plays its own game and can not legitimize other language games. So the game of the prescription is slipping. And most importantly, she can no longer legitimize herself as speculation suggests. Two major amendments are now subject to the regulation of the pragmatics of the study. They are the enrichment of the arguments and complications in the presentation of evidence, which means the finding of a fact. The need for evidence is growing more and more, as the pragmatics of scientific knowledge shifts traditional or emerging knowledge. A legitimation is formed through the power, which means that the more we can have the scientific knowledge and the power to make decisions, the more they will strengthen the techniques. And the power itself is increased by the purchase of scientists, technicians and apparatuses. Moving on to the other aspect of knowledge, teaching him the question of his transmission through a series of questions: "Who betrays? What? Whom? By what? In what form? What effect? "6 * University politics says that Lyotard is built from the sum of the answers to these questions. The essence of the transmission consists in organizing a pool of knowledge. Knowledge transfer will no longer be designed to form an elite that will lead the nation but create players to play their role in pragmatic posts that institutions need. It will no longer be necessary to teach lectures live by a professor, the didactics will be entrusted to machines containing data banks and these machines will be made available to the students. This will open a large market for operational competencies, the supporters of this knowledge will be subject to proposals and a pledge in seduction policies.

Lyotard says that some scientists have already said that the brightest feature of postmodern scientific knowledge is the immanence of discourse over the rules that make it stand out. The thought of losing legitimacy and falling into philosophical pragmatism at the end of the nineteenth century was nothing more than an episode. The recourse to great accounts according to Lyotard is already excluded, can not be used either to the dialectic of the Spirit or to the emancipation of mankind in order to justify the postmodern scientific discourse. The little story remains a form of imaginative invention first in science. Lyotard wants to find out if a legitimacy is possible, referring only to parlology. For this purpose, the parody of the innovation must be distinguished. The review shows that "the theory of systems and the type of legitimation it offers have no scientific basis. Postmodern is what introduces the unpredictable into the very idea. In the dispute of modernity-postmodernity, Lyotard takes the side of postmodernism. The postmodern artist is in the situation of a philosopher: the text he has written is no longer guided by pre-established rules. These rules or categories are searched in the very text of the work.