Marginalised Rights

It is not uncommon, especially during Pride Month™, to hear the phrase, “Trans rights are human rights!” A political slogan certainly, but a slogan worthy of analysis nonetheless.

First, one needs to change the form the argument is given. In predicate logic, it becomes:  where

where  =x is a trans right,

=x is a trans right,  =x is a human right, and r is any given right. Non-mathematically, this would be expressed as follows: if a given right is a trans right, then it is also a human right. This is done not to misrepresent the argument, rather to ideally formulate it analytically.

=x is a human right, and r is any given right. Non-mathematically, this would be expressed as follows: if a given right is a trans right, then it is also a human right. This is done not to misrepresent the argument, rather to ideally formulate it analytically.

What exactly is a right? A right is a power or privilege given by some authoritative entity, such as a deity or a legal institution. The former, which could be called a “God-given right”, will not be handled here; as it is the latter entity that gives rights in a concrete, Material sense (not an abstract, Ideal one), the latter is to be assessed. Here the practical is important, not the abstract.

In this sense, therefore, human rights are powers or privileges given to humans by whichever legal institution dictates over the given jurisdiction. For myself, being in the UK, human rights are in part codified in the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The ECHR defines just shy of two dozen human rights. These could be called primary rights; i.e., rights that are not derived from other rights and that are the roots of derivations that result in what could be called secondary rights. Secondary rights are rights applied to certain groups as subsets of humanity; i.e. applications that are not functionally universal. These are primary and secondary purely in terms of derivation and not in terms of importance. An example of a secondary right would be the right to gay marriage: the right for gay people to marry is a right functionally applied only to non-straight people--though technically straight people could use it--and can be derived from Article 12 of the ECHR, the right to marriage (though more on that later).

The slogan--that “trans rights are human rights”--posits that trans rights are secondary rights, derived from the superset of the primary human rights, which specifically apply to transgender people. An example of a trans right, under this model, could be the right the transition or to express one’s gender identity (derived from Article 10 of the ECHR, the right to freedom of expression).

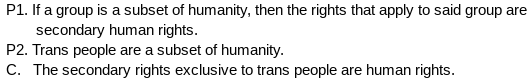

Hence, the argument in support of the slogan is as follows:

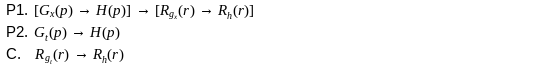

Or, in predicate logic:

Where  =y is a human right of group x,

=y is a human right of group x,  =y belongs to some variable group x (

=y belongs to some variable group x ( thus meaning y is a right of group x),

thus meaning y is a right of group x),  =x is trans (

=x is trans ( thus meaning y is a right of trans people),

thus meaning y is a right of trans people),  =x is human (

=x is human ( thus meaning y is a right of humans), p=any given human, and r=any given right.

thus meaning y is a right of humans), p=any given human, and r=any given right.

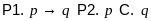

It is as simple as  (if p then q, p, therefore q), so it is valid in form. Hence to defeat this argument one must disprove one of the premises. The first premise is inductively falsifiable by the absence of any such cases. However, a derived right of Article 9 of the ECHR, the right to a religion (among other rights), is that Muslim children in primary school are allowed to fast during Ramadan. Likewise, this applies to the social majority; Christians are allowed to perform their various religious practises as secondary rights. Hence, premise one is true.

(if p then q, p, therefore q), so it is valid in form. Hence to defeat this argument one must disprove one of the premises. The first premise is inductively falsifiable by the absence of any such cases. However, a derived right of Article 9 of the ECHR, the right to a religion (among other rights), is that Muslim children in primary school are allowed to fast during Ramadan. Likewise, this applies to the social majority; Christians are allowed to perform their various religious practises as secondary rights. Hence, premise one is true.

The next premise is--also inductively--falsifiable by demonstrating the presence of transgender non-humans or the absence of transgender humans. To be transgender is to identify with a gender that one was not assigned at birth. Gender has not been demonstrated to exist in non-humans but has been demonstrated to exist in humans, so it seems likely to be a phenomenon exclusive to humans. Hence, the second premise stands.

Given that both premises stand strong, that falsifiability thereof was unsuccessful, the conclusion that trans rights are human rights also stands. Hence, it seems that unless the unlikely is true--that there are transgender non-humans (which would only alter the form of this argument anyway and change much of sociology)--the slogan maintains its truth-value regardless of whether or not it has use-value (in a non-economic sense; rather, the value there is in using it as a political slogan).

Having already explored the truth-value of the statement, the other side of the coin is its use-value. The ECHR, and other codified sets of primary human rights, is not perfectly used. For instance, the earlier mentioned Article 12, the right to marriage, has been frequently denied to be used in favour of gay marriage despite no such exclusion being written (it is written as “men and women of marriageable age have the right to marry [...]”, not “a man and a woman of marriageable age have the right to marry one another [...]”)--this is simply a byproduct of homophobia. Similarly, the actual article itself fails to recognise non-binary people (particularly those who are neither men nor women) as deserving of the right to marriage. Human rights legislation seems to be non-inclusive both in its actual concrete writing and its interpretation.

It seems, therefore, that the intricacies of the phrase, “trans rights are human rights”, are deeper than immediately considered. It is both a descriptive and a normative claim; it says not only that trans rights are protected as human rights, but also that they ought to be--both in legislation and in the execution thereof.

Trans rights are human rights. ✊