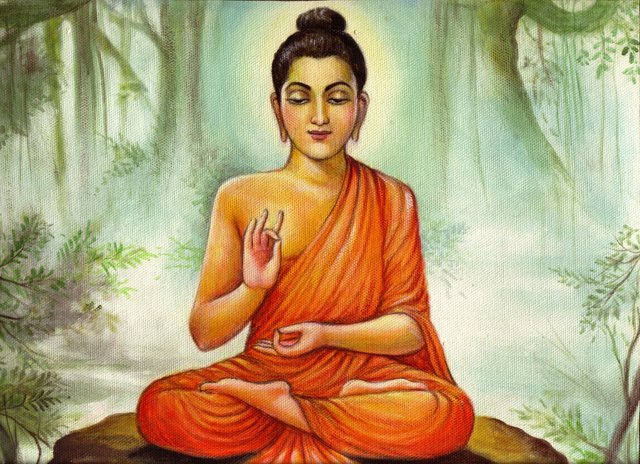

Buddha, a lonely human rebel

Buddha's philosophy was a rebellion against the superstitious Hinduism of his days.

Although I do not consider myself a Buddhist, I have always had much respect for Gautama Buddha and I have always regarded him as an exemplary person.**

What I find most sympathetic about Buddha are his humanness, his epistemological modesty, and his insistence to use reason and scientific inquiry to understand the world. It is for these reasons that Gautama Buddha could be considered contumacious or rebellious; he argued tenaciously against the superstitious practices and beliefs of Hinduism. He encouraged his followers to cultivate the mind and develop reason, because he considered it to be an essential element of ‘magga’ or the eightfold path to enlightenment (right understanding, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration).

Smith & Novak write in Buddhism (2003) that there are six aspects of religion that “surface so regularly as to suggest that their seeds are in the human makeup” (Smith & Novak, 2003, p. 22), and that Gautama Buddha rebelled against all these aspects. The six aspects are:

1. Authority – which was hereditary and exploitative as brahmins were charging exorbitantly for their services;

2. Rituals – which became the people’s mechanical means to achieve quick miraculous results in life;

3. Speculation – which entirely lost its experiential base;

4. Tradition – which inhibited people from progress. One example is the tradition to instruct religious discourse in Sanskrit, making the brahmins’ knowledge effectively unavailable for the common people;

5. Divine grace – which became confused with fatalism as to undercut human responsibility. Think for instance about the misinterpretation of ‘karma’ that was abused in order to maintain and rationalize the caste system;

6. Mystery – which became confused with mystification and led to a perverse obsession with miracles and the occult. (Smith & Novak, 2003, p. 23)

According to Gautama Buddha, they were all too prevalent in the Hinduism of his days and he regarded them to be oppressive of human flourishing. As a revolt against the superstitious Hindu culture, Gautama Buddha preached a philosophy that is:

A. Devoid of authority – he tried to break the brahmins’ monopoly on religious teachings. In addition, he challenged everyone to utilize their own rationality and stop passively relying on the brahmins to tell them what to do.

B. Devoid of rituals – he believed that rites and ceremonies bind the human spirit.

C. Devoid of speculation – the monk Malunkyaputta, troubled by Gautama Buddha’s silence on metaphysical speculations, said:

whether the world is eternal or not eternal, whether the world is finite or not, whether the soul is the same as the body, or whether the soul is one thing and the body another, whether a Buddha exists after death or does not exist after death, whether a Buddha both exists and does not exist after death, and whether a Buddha is non-existent and not non-existent after death, these things the Lord does not explain to me, and that he does not explain them to me does not please me, it does not suit me (Kyimo, 2007, p. 206).

D. Devoid of tradition – he wanted a break from the archaic and he wanted to teach the peoples in their vernacular. On the question why his teachings should be followed, Gautama Buddha answers:

Do not go upon what has been acquired by repeated hearing; nor upon tradition; nor upon rumor; nor upon what is in a scripture; nor upon surmise; nor upon an axiom; nor upon specious reasoning; nor upon a bias toward a notion that has been pondered over; nor upon another’s seeming ability; nor upon the consideration, ‘The monk is our teacher.’ Kalamas, when you yourselves know: ‘These things are bad; these things are blamable; these things are censured by the wise; undertaken and observed, these things lead to harm and ill,’ abandon them.[1]

What Gautama Buddha is effectively saying here is that everything should be questioned; every tradition, every holy book, and even teachers including himself. He taught everyone to use reason and the scientific methodology of inquiry, and he emphasized on doing good and abandoning evil.

E. Emphasizes intense self-effort and opposes fatalism – everyone can become enlightened. He taught everyone that actions are meaningful and that everyone contains the power to change their lives immediately for the better. Everyone was considered responsible for their own actions and happiness. This puts heavy responsibilities on all individuals to make the best of their lives.

F. Devoid of the supernatural – he condemned divination and reliance on Brahma (God). (Smith & Novak, 2003, pp. 24-28) He could not conceive of Brahma who considered himself

the Supreme one, the Mighty, the All-seeing, the Ruler, the Lord of all, the Maker, the Creator, the Chief of all appointing to each his place, the Ancient of days, the Father of all that is and will be[2]

to inflict so much suffering on the peoples:

If the creator of the world entire

They call God, of every being be the Lord

Why does he order such misfortune

And not create concord?

If the creator of the world entire

They call God, of every being be the Lord

Why prevail deceit, lies and ignorance

And he such inequity and injustice create?

If the creator of the world entire

They call God, of every being be the Lord

Then an evil master is he, (O Aritta)

Knowing what’s right did let wrong prevail![3]

At the same time, Gautama Buddha appeared to be one of us: fallible, sensitive, and insecure about life. Despite his immense influence, he remained humble enough as to never claim to be a son or a prophet of God – nor did he ever claim to understand the beginnings of the universe. His teachings were entirely devoted to alleviate man from his misery.

Talking about the Three Greatest Men In History (1935), H.G. Wells said of Gautama Buddha that:

[Y]ou see clearly a man, simple, devout, lonely, battling for light – a vivid human personality, not a myth. Beneath a mass of miraculous fable I feel that there also was a man. He, too, gave a message to mankind universal in its character. Many of our best modern ideas are in closest harmony with it. All the miseries and discontents of life are due, he taught, to selfishness… Before a man can become serene he must cease to live for his senses or himself. Then he merges into a greater being. Buddha in different language called men to self-forgetfulness 500 years before Christ. In some ways he was nearer to us and our needs. He was more lucid upon our individual importance in service than Christ and less ambiguous upon the question of personal immortality. (Wells, 1935, July 13)

Footnotes

[1] From Kalama Sutta: The Instruction to the Kalamas.

[2] From Digha Nikaya 1: Brahmajala Sutta.

[3] From Bhuridatta Jakata.

Bibliography

Examiner. (1935, July 13). Greatest In History. Retrieved from www.trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/51945346?searchTerm=GLOBE%20READER%20DIGEST%20&searchLimits=

Gunasekara, V.A. (1997). The Buddhist Attitude To God. Retrieved from http://www.budsas.org/ebud/ebdha068.htm

Kalama Sutta: The Instruction to the Kalamas. (1994), Transl. Soma Thera. Retrieved from www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/an/an03/an03.065.soma.html

Kyimo. (2007). The Easy Buddha. London: Prospect House Publishing.

Smith, H., & Novak, P. (2003). Buddhism: A Concise Introduction. New York: HarperOne.