The lost art of arguing

My debates with statists has inspired me to write this topic, and I'm going to be splitting this article into two parts: first, I'm going to write about why many people don't know how to argue well, and then I'll try to give useful tips and advice on debating effectively.

Part One

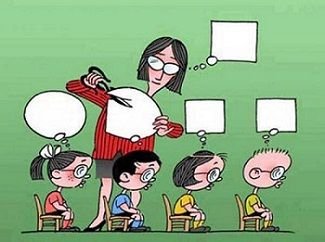

To start, the main reason why the majority don't know how to make sound or coherent arguments is because they have been conditioned out of critically thinking by being subjected to the public educational system, modelled after the Prussian system, which emphasizes repetition, memorization, and obedience. These acts don't cause or motivate individuals to think and learn for themselves; instead, they are trained to just accept what is taught to them without understanding the concepts of logic or truth.

For example, the normal process of "teaching" in public schools is simply putting forth statements to students, and later testing how well they remember what they were taught, rewarding them for regurgitating what they were told as opposed to encouraging them to figure out how and why what is being taught to them relates to reality (if it does, anyways) through reasoning.

As a result, it becomes harder for people to critically think over time to the point where they actively try to avoid it, since they didn't exercise this skill as much as they could have before. This leads me to my next point: another reason why the average person is bad at arguing rationally is because he/she hardly has to throughout his day-to-day life. Many regular jobs don't require complex problem solving; they just require people to perform some repetitive processes. In addition, most aren't interested in having deep philosophical discussions related to morality, justice, truth, logic and so on, which makes it even less likely that they will have to use their critical thinking for anything meaningful.

Part Two

Here are a few word-for-word examples of bad arguing I've encountered while debating, mainly because they don't address my points and aren't backed up by anything.

"What a pile of crap."

"This is just comically simplistic thinking."

"Pseudointellectual nonsense."

The last two demonstrate a common habit I see during discussions and debates: assuming that sounding smart by using fancy words gives you bonus points and helps you win arguments, when it doesn't. What matters is substance, which can be conveyed using either rather simple or advanced vocabulary. For instance, I can say:

He should have ceased to press on the gas pedal upon arriving at the red light, as it is hazardous to fail to come to a halt at red lights.

or:

He should have stopped at the red light, because it's dangerous not to stop at red lights.

Both sentences mean the same thing, and the point (or the substance in this case) is that he shouldn't skip red lights because it's dangerous. In fact, if I remove the second part of the more impressive-looking sentence --

He should have ceased to press on the gas pedal upon arriving at the red light.

-- it says less than the simpler sentence, since it doesn't state why he shouldn't run red lights, while the second one at least mentions that he shouldn't because it's dangerous. Even so, the simpler sentence doesn't make a convincing case either, as it doesn't explain why it's dangerous.

An argument clearly outlines the topic or subject, the relevance of the argument to the topic, and the argument itself. Breaking down the above example, the topic is the fact that the person skipped a red light, the argument is that he shouldn't have skipped the red light because it's dangerous to run red lights, and the relevance to the subject is that he himself ran a red light.

An effective argument, on the other hand, is also substantiated using evidence and/or reasoning, as it doesn't carry any weight on its own. What seems obvious to you may not seem obvious to whoever you're debating, and if he doesn't understand what you're arguing or why, it's pointless to continue the discussion, as it will be near impossible to address the crucial areas of disagreement, which is why it's important to define and reinforce your arguments.

It is also important to personally understand your beliefs, and why you hold those beliefs. This goes back to public schooling: if the main reason someone believes something is because he was taught it, that's not a very good reason in and of itself, as he can be "taught" anything; it doesn't necessarily make it true. Basing one's beliefs off of a small number of observations and experiences is also a bad reason to have those beliefs, as you most likely won't have the entire picture.

These faulty reasons lead to arguing from a false premise, where the main argument and subsequent related arguments are wrong because the root of the main argument is wrong; another common pitfall. Just recently, when I was debating the nature of government with someone, he mentioned that Hitler was elected by the people, which is an example of a false premise, since he wasn't elected; he was made "Fuhrer" through a law enacted by the German Cabinet.

In conclusion, a good debater uses facts and evidence that are observable in the real world and double-checks those facts.

P.S. I added the voluntaryism tag as well because it's important for us voluntaryists to be able to spread the principles of self-ownership and non-aggression by arguing for them effectively.