Snowden Designs a Device to Warn If Your iPhone’s Radios Are Snitching

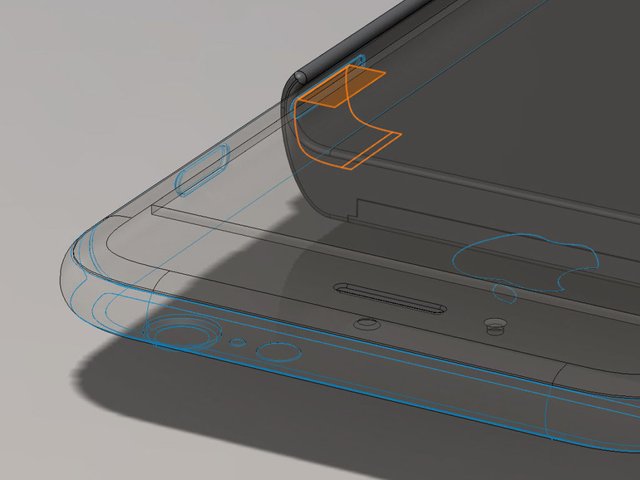

A mockup of Edward Snowden and Bunnie Huang's iPhone modification, showing the SIM card slot through which their hardware add-on would access the phone's antennae to monitor them for errant signals. ANDREW HUANG & EDWARD SNOWDEN

https://www.wired.com/2016/07/snowden-designs-device-warn-iphones-radio-snitches/

WHEN EDWARD SNOWDEN met with reporters in a Hong Kong hotel room to spill the NSA’s secrets, he famously asked them put their phones in the fridge to block any radio signals that might be used to silently activate the devices’ microphones or cameras. So it’s fitting that three years later, he’s returned to that smartphone radio surveillance problem. Now Snowden’s attempting to build a solution that’s far more compact than a hotel mini-bar.

On Thursday at the MIT Media Lab, Snowden and well-known hardware hacker Andrew “Bunnie” Huang plan to present designs for a case-like device that wires into your iPhone’s guts to monitor the electrical signals sent to its internal antennas. The aim of that add-on, Huang and Snowden say, is to offer a constant check on whether your phone’s radios are transmitting. They say it’s an infinitely more trustworthy method of knowing your phone’s radios are off than “airplane mode,” which people have shown can be hacked and spoofed. Snowden and Huang are hoping to offer strong privacy guarantees to smartphone owners who need to shield their phones from government-funded adversaries with advanced hacking and surveillance capabilities—particularly reporters trying to carry their devices into hostile foreign countries without constantly revealing their locations.

“One good journalist in the right place at the right time can change history,” Snowden told the MIT Media Lab crowd via video stream. “This makes them a target, and increasingly tools of their trade are being used against them.”

“They’re overseas, in Syria or Iraq, and those [governments] have exploits that cause their phones to do things they don’t expect them to do,” Huang elaborated to WIRED in an interview ahead of the MIT presentation. “You can think your phone’s radios are off, and not telling your location to anyone, but actually still be at risk.”

A mockup of the design of the “introspection engine” for the iPhone 6 that Huang and Snowden are proposing. ANDREW HUANG & EDWARD SNOWDEN

Huang’s and Snowden’s solution to that radio-snitching problem is to build a modification for the iPhone 6 that they describe as an “introspection engine.” Their add-on would appear to be little more than an external battery case with a small mono-color screen. But it would function as a kind of miniature, form-fitting oscilloscope: Tiny probe wires from that external device would snake into the iPhone’s innards through its SIM-card slot to attach to test points on the phone’s circuit board. (The SIM card itself would be moved to the case to offer that entry point.) Those wires would read the electrical signals to the two antennas in the phone that are used by its radios, including GPS, Bluetooth, Wi-Fi and cellular modem. And by identifying the signals that transmit those different forms of radio information, the modified phone would warn you with alert messages or an audible alarm if its radios transmit anything when they’re meant to be off. Huang says it could possibly even flip a “kill switch” to turn off the phone automatically.

“Our approach is: state-level adversaries are powerful, assume the phone is compromised,” Huang says. “Let’s look at hardware-related signals that are extremely difficult to fake. We want to give a you-bet-your-life assurance that the phone actually has its radios off when it says it does.”

You might think you can achieve the same effect by simply turning your iPhone off with its power button, or placing it in a Faraday bag designed to block all radio signals. But Faraday bags can still leak radio information, Huang says, and clever malware can make an iPhone appear to be switched off when it’s not, as Snowden warned in an NBC interview in 2014. Regardless, Huang says their intention was to allow reporters to reliably disable a phone’s radio signals while still using the device’s other functions, like taking notes and photographs or recording audio and video.

Snowden, who performed the work in his capacity as a director of the Freedom of the Press Foundation, adds that their goal isn’t merely just protection for journalists. It’s also detection of otherwise stealthy attacks on phones, the better to expose governments’ use of hidden smartphone surveillance techniques. “You need to be able to increase the costs of getting caught,” Snowden said in a video call with WIRED following the presentation. “All we have to do is get one or two or three big cases where we catch someone red-handed, and suddenly the targeting policies at these intelligence agencies will start to change.”2

The problem, for Snowden, is personal. He tells WIRED he hasn’t carried a smartphone since he first began leaking NSA documents, for fear that its cellular signals could be used to locate him. (He notes that he still hasn’t “seen any indication” that the U.S. government has been able to determine his exact location in Russia.)

“Since 2013, I haven’t been able to have a smartphone like normal people,” he says. “Wireless devices are kind of like kryptonite to me.”

Huang and Snowden’s iPhone modification, for now, is little more than a design. The pair has tested their method of picking up the electrical signals sent to an iPhone 6’s antennae to verify that they can spot its different radio messages. But they have yet to even build a prototype, not to mention a product. But on Thursday they released a detailed paper explaining their technique. They say they hope to develop a prototype over the next year and eventually create a supply chain in China of modified iPhones to offer journalists and newsrooms. To head off any potential mistrust of their Chinese manufacturers, Huang says the device’s code and hardware design will be fully open-source.

Huang, who lives in Singapore but travels monthly to meet with hardware manufacturers in Shenzhen, says that the skills to create and install their hardware add-on are commonplace in mainland China’s thriving iPhone repair and modification markets. “This is definitely something where, if you’re the New York Times and you want to have a pool of four or five of these iPhones and you have a few hundred extra dollars to spent on them, we could do that.” says Huang. “The average [DIY enthusiast] in America would think this is pretty fucking crazy. The average guy who does iPhone modifications in China would see this and think it’s not a problem.”

The two collaborators have never met face-to-face. Snowden says he first met Huang after recommending him to television producers at Vice, who were looking for hardware hacking experts. “He’s one of the hardware researchers I respect the most in the world,” Snowden says. In late 2015, they began talking via the encrypted communications app Signal about Snowden’s idea of building an altered phone to protect journalists from advanced attacks that could compromise their location.

Huang insists that Snowden’s focus for the project from the beginning has been protecting that breed of vulnerable reporters, not from the NSA, but from foreign governments that are increasingly able to buy zero-day vulnerability information necessary to compromise even hard-to-hack targets like the iPhone. As a case study, they point in their paper to the story of Marie Colvin, the recently murdered American war correspondent whose family is suing Syria’s government; Colvin’s family claims she was tracked based on her electronic communications and killed in a targeted bombing by the country’s brutal Assad regime for reporting on civilian casualties.

Huang says he’s tried to develop the most no-frills protection possible that still meets Snowden’s rightfully paranoid standards. “If it wasn’t for the fact that Snowden is involved, I think this would seem pretty mundane,” Huang says almost bashfully. “My solution is simple. But it helps an important group of people.”