A Personal Critique (with ramblings) on C.S. Lewis’ An Experiment in Criticism

(Or, an attempt to summarize a 95-page essay. Or, an attempt to write even when I don’t have to - or something like that…)

Seriously though, why bother when AI can instantly generate a cleaner, smoother summary in seconds, while I’ve spent sleepless nights and weekends grappling Lewis, who isn’t exactly the easiest to read?

Why? Why bother?

Fortunately, Kate Wagner, the architecture critic and essayist, gave the simplest answer: at the end of the day, the only true reward in writing something is having written it.

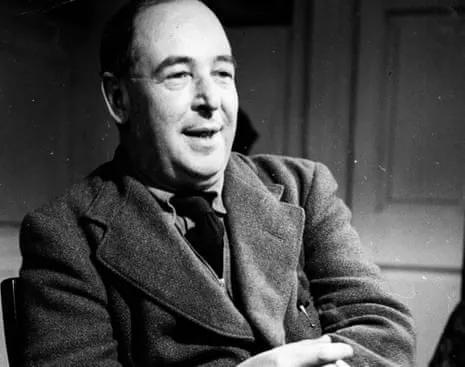

I would have called this a review, but after reading through the whole piece, I realised it was nothing but ramblings - mostly about Lewis himself. Yes, I tried summarizing his ideas, but I couldn’t help the fact that Lewis’ person is constantly emanating from his prose. It makes me not only think about what he’s saying, but who he is - the man behind the words. There’s a sense of integrity so deeply woven into his writing that I feel he’s really connected to every thought he puts down.

In short, he writes what he does, does what he writes.

They say one should not judge a writer by their character when reading their work, and I don’t necessarily disagree. However, I’m coming to realise that I’m far more likely to appreciate the ones who actually embody what they write.

A Bit of Backstory

Part of the reason I wanted to write this piece is because, in my opinion, rating books is often misleading. We’re quick to call a book “bad” simply because it doesn’t resonate with us. But that doesn’t make it bad. A book might seem boring or bad to one person simply because they’re reading it poorly - impatiently, or superficially.

Sometimes we complain that a story meanders. But often, that’s by design. The author wants us to linger in those moments, to slow down and absorb something beyond the plot. Like it or not, most writers write for their own ends: to explore political or social themes, or to work through personal feelings and problems. Sometimes, they choose not to show everything through action or character, but to directly tell or offer their own perspective.

Going back to Lewis.

Literary Criticism, what about it?

According to Lewis, the traditional approach to literary criticism is to judge the book first, and then the reader who enjoys it. It judges readers based on the books they like. Thus, bad taste just means liking bad books.

In this essay, he proposes an experiment by reversing the typical process of judgment. He suggests first examining how readers engage with books and then defining what makes a book 'good' or 'bad’.

What Lewis is essentially saying is: how we read matters more than what we read, and that bad reading habits lead to bad criticism.

I. The Few and the Many

Lewis divides readers into two broad camps: the many (unliterary) and the few (literary).

The unliterary person, he says, never reads anything twice. A finished book is discarded like a burnt-out match. They read often, but rarely with intention. They read to fill time - during commutes or idle moments, and then as soon as something more entertaining appears, they quickly abandon it. Reading, for them, is a mere pastime. Consequently, they rarely reflect or gain anything that might change them.

The literary reader, on the other hand, returns to great works over and over. They read deliberately. The first reading of a book is often transformative - they are not the same person afterward. Favourite lines are revisited, repeated in solitude, and discussed with others in search of deeper understanding.

But please don’t be too quick to categorise yourself. These are only surface traits, and the more you read Lewis, the more you’ll find yourself shifting between categories. (Like I did.)

II. False Characterisation

The real lovers of literature might just be the quiet, devoted re-readers who are changed by what they read.

I guess nothing escapes Lewis, not even the subtlest pretentions. The so-called experts - connoisseurs, critics, or pedants don’t necessarily embody literary depth. Maybe they once loved books, but over time, money or status started to matter more than words. Lewis refers to them, quite plainly, as mere professionals.

I really admire how Lewis insists, implicitly but clearly, that we approach literature, or any form of art, with humility. I believe this comes from his Christian background, which I don’t totally oppose because it’s the most reasonable approach. It’s not about being humble for humility’s sake, that would be foolish, but reverence for the craft and the craftsman.

A devotee of culture

Lewis gives another defining trait of the unliterary - one that, when I first read it, made my blood run cold. He calls it “a devotee of culture.” On the surface, this person may display many literary traits, but with a little more digging, it becomes clear: he belongs with the unliterary.

This devotee of culture treats literature, or any art, as a means to an end - a tool for insight, status, or self-improvement. Lewis argues that the best reading begins with surrender, not analysis: approaching stories openly, without agendas, and letting ourselves get lost in them. You play football for the thrill of scoring goals, not because it's a good workout. As he says, a true reader “will never try to munch whipped cream as if it were venison.”

I’m guilty of this, especially with Dostoyevsky. I often read him through the lens of spiritual existentialism. But in my defence, his work seems to invite exactly that, his novels practically dare you to wrestle with their ideas.

III. How the Few and the Many Use Pictures and Music

I find this chapter especially compelling as it still rings true even to this day. Lewis nails the way people (the 'many') so often approach art. Instead of stepping back and actually experience it for what it is, they rush to make use of it.

Paintings are no longer seen as the painter's vision, nor do viewers allow themselves to get lost in the artist's imagination. No. Art is barely given time to speak for itself. The art is lost, and worse: it's reduced to a mere tool - a tool to flaunt sophistication or pretend to have a 'refined' taste.

The same happens with music. The majority listen selectively, picking out only the catchy tunes and ignoring the rest of the piece.

In contrast, the few engage in what Lewis calls ‘disciplined reception.’ They surrender to the art, allowing it to shape their response rather than dictating it. They are like those who can sit through an entire orchestral performance quietly, attentively, and patiently, waiting to see how the whole thing unfolds. Of course, this isn’t to say that the few never hum or whistle to the tune. They do, but not while the music is still playing. It’s much like how we recite our favourite verses or lines to ourselves, after the reading is done.

Lewis writes:

“The first demand any work of any art makes upon us is surrender. Look. Listen. Receive. Get yourself out of the way. (there is no good asking first whether the work before you deserves such a surrender, for until you have surrendered you cannot possibly find out.)”

So, I presume you’ve already found yourself switching camps. Lewis reassures us that this is perfectly normal - along the way, people often shift from the ‘many’ to the ‘few’, and sometimes back again. But when a young reader first begins that transition from the “many” to the “few,” a kind of transient error can arise.

Lewis points out how new “serious” readers can slip into a kind of self-important snobbery - dismissing anything accessible as cheap or sentimental. I've definitely caught traces of this in myself at times. But Lewis is generous here, he sees it as a passing phase for true lovers of art, though a lasting trap for those more interested in status than in literature itself.

IV. The Reading of the Unliterary

One thing I’ve noticed while reading Lewis (and what strongly draws me to him) is his talent for explaining abstract concepts in a way that’s easily comprehensible, by comparing them to something tangible or familiar. He can be wordy, but in a helpful, purposeful way. Only after you’ve listened to him will you realise that you needed those nuances after all. The more he offers you those nuances, the clearer the picture becomes. Of course, this process is not without difficulty. It takes getting used to his style of prose.

In this chapter, Lewis offers a long exposition on the shared trait between the unmusical and the unliterary: both engage with art in a very selective and arguably selfish way. Their own interests comes first; only taking in what immediately feels good or useful, while the rest is rejected.

The unmusical person listens only to the catchy tune and ignore all the other sounds in the orchestra. Similarly, the unliterary reads only for the plot; they want something to always be happening and fast. They don’t care about good writing style or bad writing style. Dialogues are an obstruction to them. Anything that slows the pace is a nuisance.

All these judgments, Lewis pointed out, depend on first taking the words seriously. Unless we make a genuine effort to see through the lens of the artist, we can’t truly tell whether the work is good or bad. As he puts it:

“We can never know that a piece of writing is bad unless we have begun by trying to read it as if it was very good and ended by discovering that we were paying the author an undeserved compliment.”

In other words, goodwill must take precedence. Only then can we fairly say whether it lived up to our trust.

Of course, that’s easier said than done. I think it takes a certain maturity, and maybe a bit of unlearning, to truly read this way.

To be continued…

The next chapters are On Myths, the Meanings of Fantasy, Realisms, Poetry, the Misreading of the Literary. But maybe I’ll write about them in another post, and for a good reason. I wanted to read a book on myths and fantasy first so that I can put Lewis’ ideas to test and avoid parroting him.

Sure, I’ve read myths, but only in the sense that they feel mythical like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, or The Princess and the Goblin. But to be honest, I’m mostly reading nonfiction these days. And I don’t count Dostoyevsky as fiction - I’d rather read him for philosophical therapy than pick up a philosophy textbook.

I’m not well-read in the strict sense. I haven’t read widely. I’ve kept a small society of authors: Thoreau, C.S. Lewis, and Dostoyevsky. Of course, I read others - but I always return to these three, both in terms of writing style and world of thought. The first two have contributed most in shaping my values. The third is my therapist.

I'm not surprised to learn that I'm quite an unliteray person.

I don't remember if I have ever surrendered to a book but yeah I do appreciate good words and there are some books which transformed me even if temporarily.

This. I like this statement.

Neither do I, probably because we were never taught to.

I'm still thinking about which category I want to fall into ;-)) Both seem to offer suitable facets... Does it help if I say: no matter how much a book appeals to me or not when I'm reading it, I have to finish it. I can't just leave it halfway through. I can't do that. (Yes, I have compulsive tendencies ;-)) But that probably makes me not literary, but rather bibliomaniacal...

Why not both? Lewis' categorisation need not be rigid. You undeniably have that literary streak whether you admit it or not :-))

But you’ve introduced a really interesting nuance… it got me thinking: just because I keep revisiting my favourite lines and talking about them, it doesn’t make me literary - just an overthinker, which is probably the case most of the time.

You are nominated by True Colours - @ solperez

https://steemit.com/hive-166405/@wakeupkitty/true-colours-report-week-3#@wakeupkitty/t1fn6z

chriddi, moecki and/or the-gorilla

Hui, the team is alive!!

You witnessed some coding tests including an auto-comment that was forgotten to be deleted.

Are you sure? ;-)) May be it's not a bug but a feature... You could play with it.