Basic Lessons From Economics To Get You Through Life

10 Lessons From Economics - I see many misinformed people talk about economics and what governments should do or should not do with no basic understanding of how things work. I am going to provide a short list on 10 lessons that will help you understand how decisions are made and the principles that underline general economic theory.

This list of principles was developed Nicholas Gregory Mankiw, who is an American macroeconomist and professor at Harvard University. Let us get on with it then

Lesson 1: People face trade-offs

You may have heard the saying: "There is no such thing as a free lunch". To get one thing that we like, we usually have to give up another thing that we like. Making decisions requires trading off one against another. Consider parents when deciding on how to spend their family income. They can buy food or clothing, or have a holiday. When they choose to spend an extra dollar on one of these goods, they have one less dollar to spend on some other goods. The same applies to government policies; there is always a trade off between equity (equal) and efficiency (productivity).

Acknowledging that not every decision is black and white, people are likely to make good decisions if they realise the options available to them.

Lesson 2: The cost of something is what you give up to get it

We call this opportunity cost. The opportunity cost of an item is what you give up to get that item. When making any decision, decision makers should be aware of the opportunity costs that accompany each possible action. Opportunity costs may be tangible (money) or intangible (time). For example if you give up a night of partying with your friends to study the opportunity cost is the cost of the night out and your enjoyment. Often times when governments are creating policies that must give up something to gain something.

Lesson 3: Rational people think at the margin

Economists normally assume that people are rational. Rational people systematically and purposefully do the best they can do to achieve their objectives given the opportunities they have. Rational people know that decisions in life are rarely black and white but usually involve shades of grey.

At dinnertime, the decision you face is not between fasting or eating like a pig but whether to take that extra spoonful of mashed potatoes. When exams roll around, your decision is not between blowing them off or studying 24 hours a day but whether to spend an extra hour reviewing notes. Economists call this marginal change. People usually make decisions by comparing marginal benefits and marginal cost.

Lesson 4: People respond to incentives

An incentive is something that induces a person to act, such as the prospect of a punishment or a reward. Because rational people make decisions by comparing costs and benefits they respond to incentives. Incentives are crucial for analysing how markets work. For example, when the price of an apple rises, for instance, people decide to eat fewer apples. At the same time, apple orchards decide to hire more workers and harvest more apples. In other words, a higher price in a market provides an incentive for buyers to consume less and an incentive for sellers to produce more.

Lesson 5: Trade can make everyone better off

Trade between one country and another is not like a sports contest, where one side wins and the other side loses. In fact the opposite is true - trade between two countries can make each country better off and, hence, worker (on average) better off.

Trade allows countries to specialise in activities they do best, whether it is farming, sewing or mining. By trading with others, countries can buy a greater variety of goods and services at a lower cost.

Lesson 6: Markets are usually a good way to organise economic activity

The collapse of communism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe in the 1980s may be one of the most important changes in the world. Most countries that once had centrally planned economies have abandoned this system and are instead developing market economies. In a market economy, the decisions of a central planner are replaced by the decisions of millions of firms and households.

This may seem like it could be chaos but the opposite is true. By not having anyone interfere in the market it will create an outcome that allocates goods and services to those people who value them most highly and makes the best use of our scarce resources. This is known as the invisible hand.

Lesson 7: Governments can sometimes improve market outcomes

If the invisible hand of the market is so great, why do we need government? One reason is that some markets only work if property rights are enforced, a farmer won't grow crops if he expects it to be stolen. Governments need to ensure market failure doesn't happen; this is when markets fail to allocate resources effectively. Other externalities and market power are reasons for government to step in. Regulating prices can be essential in certain situations, for example when there are monopolies for products that are essential to living.

Lesson 8: A country's standard of living depends on its ability to produce goods and services

Almost all variation in living standards is attributable to differences in countries' productivity - that is, the amount of goods and services produced from each hour of a workers time. The relationship between productivity and living standards also has profound implications for public policy. When thinking about how any policy will affect living standards, the key question is how it will affect our ability to produce goods and services.

Lesson 9: Prices rise when the government prints too much money

In most cases of large or persistent inflation, the culprit turns out to be the same-growth in the quantity of money. When a government creates large quantities of a nation's money, the value of their money falls. A great example of this was in Germany in 1920 when prices were tripling every month so was the money supply.

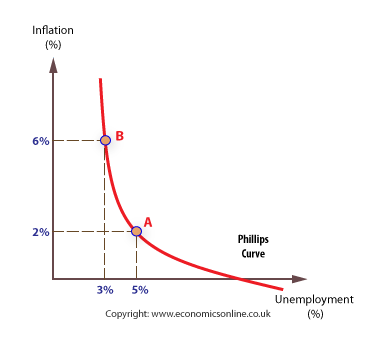

Lesson 10: Society faces a short-term trade-off between inflation and unemployment

Inflation is often thought to cause a temporary rise in unemployment. This trade-off is called the Phillips curve. This trade-off occurs because some prices are slow to adjust. For example, if the government reduces the quantity of money in the economy, in the long term the only result will be a fall in the overall prices. But not all prices will adjust immediately thus causing firms to not charge enough to maintain their costs.

Thanks for reading guys; I hope I was able to educate a few of you on some simple economic lessons to help you be a more informed person.

I might respond to this in more thoughtful form when I have the time - I like your style and appreciate your efforts, but some of what you outline is fairly routine neoclassical economics which is at the very best under some considerable pressure at the moment. The rational consumer model, for example, is increasingly in doubt. The use of markets in certain sectors has been demonstrated to be nonsensical - in healthcare or mass transport, for example. The UK's economic figures for the past 40 years are very interesting, as they cover a period of change from socialist to neoliberal politics. And the economic data, outside the benefits to a small number of wealthy people, is informative. The widening wealth gap, and lack of growth of median pay, indicate an economic model that is ineffective for a whole society, though admittedly, highly effective for the highest earners. And we haven't even mentioned privately owned natural monopolies, which eat up national wealth and convert it to tax-haven hosted corporate profit... I'll stop there, I've got work to do, I'll try to post something as a response to your post in the next few days. Take it easy

Thanks for the response. This was just a very basic guide to some principles, a high school level you could say. If you want something more in depth take a look at my other articles about brexit and South Africas educational system :)

Great stuff, I will do, thanks :)