Summary What every body is saying by Joe Navarro-First chapter

A book by Joe Navarro, Ex-FBI agent in to how speed reading people's body.

This is my summary of such an interesting book:

What is it that our body or any other person is saying. Joe, it turns out, has spent his entire professional life studying, refining, and applying the science of nonverbal communications—facial expressions, gestures, physical movements (kinesics), body distance (proxemics), touching (haptics), posture, even clothing—to decipher what people are thinking, how they intend to act, and whether their pronouncements are true or false. This is not good news for criminals, terrorists, and spies, who, under his careful scrutiny, usually give off more than enough nonverbal body signals (“tells”) to make their thoughts and intentions transparent and detectable.

It is, however, very good news for you, the reader, because the very same nonverbal knowledge Joe relied on to become a master “Spycatcher,” “human lie detector,” and instructor at the FBI is what he will be sharing with you so you can better understand the feelings, thoughts, and intentions of those around you. As a renowned author and educator, Joe will teach you how to observe like an expert, detecting and deciphering the nonverbal behaviors of others so you can interact with them more successfully. For business or for pleasure, this knowledge will enrich and magnify your life.

Following the Ten Commandments for Observing and Decoding Nonverbal Communications Successfully

Commandment 1: Be a competent observer of your environment. As Sherlock Holmes, the meticulous English detective, declared to his partner, Dr. Watson, “You see, but you do not observe.”

Commandment 2: Observing in context is key to understanding nonverbal behavior. After an accident, people are suffering the effects of a complete hijacking of the “thinking” brain by a region of the brain known as the limbic system. The result of this hijacking includes behaviors such as trembling, disorientation, nervousness, and discomfort. In context, these actions are to be expected and confirm the stress from the accident. During a job interview, I expect applicants to be nervous initially and for that nervousness to dissipate. If it shows up again when I ask specific questions, then I have to wonder why these nervous behaviors have suddenly presented again.

Commandment 3: Learn to recognize and decode nonverbal behaviors that are universal. Some body behaviors are considered universal because they are exhibited similarly by most people. For instance, when people press their lips together in a manner that seems to make them disappear, it is a clear and common sign that they are troubled and something is wrong.

Commandment 4: Learn to recognize and decode idiosyncratic nonverbal behaviors. In attempting to identify idiosyncratic signals, you’ll want to be on the lookout for behavioral patterns in people you interact with on a regular basis (friends, family, coworkers, persons who provide goods or services to you on a consistent basis). The better you know an individual, or the longer you interact with him or her, the easier it will be to discover this information because you will have a larger database upon which to make your judgments. The best predictor of future behavior is past behavior.

Commandment 5: When you interact with others, try to establish their baseline behaviors. In order to get a handle on the baseline behaviors of the people with whom you regularly interact, you need to note how they look normally, how they typically sit, where they place their hands, the usual position of their feet, their posture and common facial expressions, the tilt of their heads, and even where they generally place or hold their possessions, such as a purse. You need to be able to differentiate between their “normal” face and their “stressed” face.

Commandment 6: Always try to watch people for multiple tells—behaviors that occur in clusters or in succession. Your accuracy in reading people will be enhanced when you observe multiple tells, or clusters of behavior body signals on which to rely. To illustrate, if I see a business competitor display a pattern of stress behaviors, followed closely by pacifying behaviors, I can be more confident that she is bargaining from a position of weakness.

Commandment 7: It’s important to look for changes in a person’s behavior that can signal changes in thoughts, emotions, interest, or intent. Among the most important nonverbal clues to a person’s thoughts are changes in body language that constitute intention cues. These are behaviors that reveal what a person is about to do and provide the competent observer with extra time to prepare for the anticipated action before it takes place. Sudden changes in behavior can help reveal how a person is processing information or adapting to emotional events. Changes in a person’s behavior can also reveal his or her interest or intentions in certain circumstances. Careful observation of such changes can allow you to predict things before they happen, clearly giving you an advantage—particularly if the impending action could cause harm to you or others.

Commandment 8: Learning to detect false or misleading nonverbal signals is also critical. I will teach you the subtle differences in a person’s actions that reveal whether a behavior is honest or dishonest, increasing your chances of getting an accurate read on the person with whom you are dealing.

Commandment 9: Knowing how to distinguish between comfort and discomfort will help you to focus on the most important behaviors for decoding nonverbal communications. There are two principal things we should look for and focus on: comfort and discomfort. Learning to read comfort and discomfort cues (behaviors) in others accurately will help you to decipher what their bodies and minds are truly saying. If in doubt as to what a behavior means, ask yourself if this looks like a comfort behavior (e.g., contentment, happiness, relaxation) or if it looks like a discomfort behavior (e.g., displeasure, unhappiness, stress, anxiety, tension). Most of the time you will be able to place observed behaviors in one of these two domains (comfort vs. discomfort).

Commandment 10: When observing others, be subtle about it. Using nonverbal behavior requires you to observe people carefully and decode their nonverbal behaviors accurately. However, one thing you don’t want to do when observing others is to make your intentions obvious. Many individuals tend to stare at people when they first try to spot nonverbal cues. Such intrusive observation is not advisable. Your ideal goal is to observe others without their knowing it, in other words, unobtrusively.

COMFORT, DISCOMFORT AND PACIFIERS.

To borrow a phrase from the old Star Trek series, the “prime directive” of the limbic brain is to ensure our survival as a species. It does this by being programmed to make us secure by avoiding danger or discomfort and seeking safety or comfort whenever possible.

When we experience a sense of comfort (well-being), the limbic brain “leaks” this information in the form of body language congruent with our positive feelings. Observe someone resting in a hammock on a breezy day. His body reflects the high comfort being experienced by his brain. On the other hand, when we feel distressed (discomfort), the limbic brain expresses nonverbal behavior that mirrors our negative state of being. Their bodies say it all. Therefore, we want to learn to look more closely at the comfort and discomfort behaviors we see every day and use them to assess for feelings, thoughts, and intentions.

Example of a discomfort verbal cue is “Eye-blocking” is a nonverbal behavior that can occur when we feel threatened and/or don’t like what we see. Squinting (as in the case with my classmates, described above) and closing or shielding our eyes are actions that have evolved to protect the brain from “seeing” undesirable images and to communicate our disdain toward others.

Types of Pacifying Behaviors

Whenever there is a limbic response— especially to a negative or threatening experience—it will be followed by what I call pacifying behaviors. These actions, often referred to in the literature as adapters, serve to calm us down after we experience something unpleasant or downright nasty (Knapp & Hall, 2002, 41–42). In its attempt to restore itself to “normal conditions,” the brain enlists the body to provide comforting (pacifying) behaviors. Since these are outward signals that can be read in real time, we can observe and decode them immediately and in context.

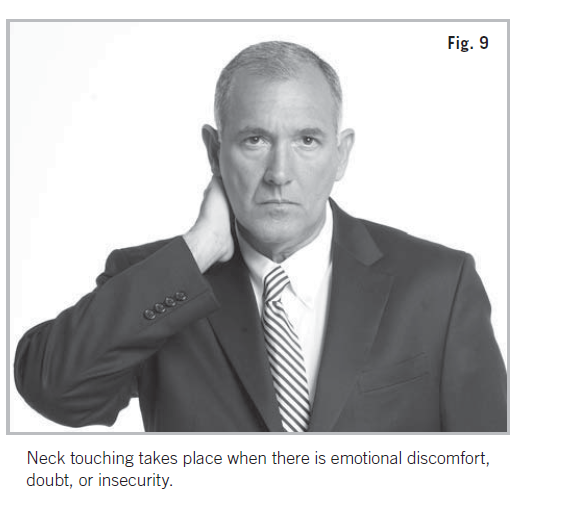

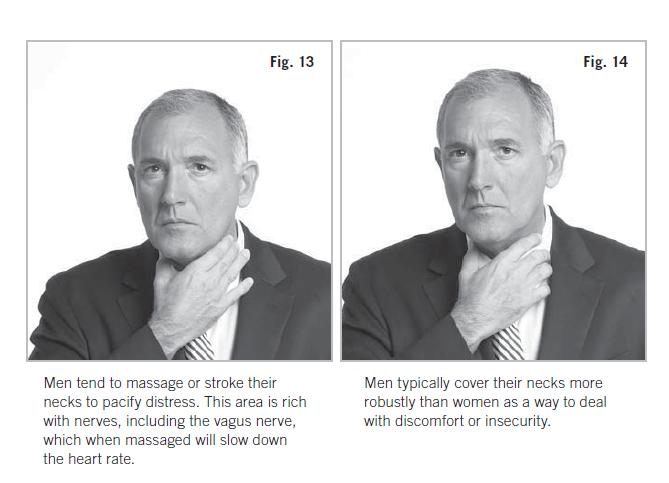

Neck touching and/or stroking is one of the most significant and frequent pacifying behaviors we use in responding to stress. When a person touches this part of her neck and/or covers it with her hand, it is typically because she feels distressed, threatened, uncomfortable, insecure, or fearful. This is a relatively significant behavioral clue that can be used to detect, among other things, the discomfort experienced when a person is lying or concealing important information.

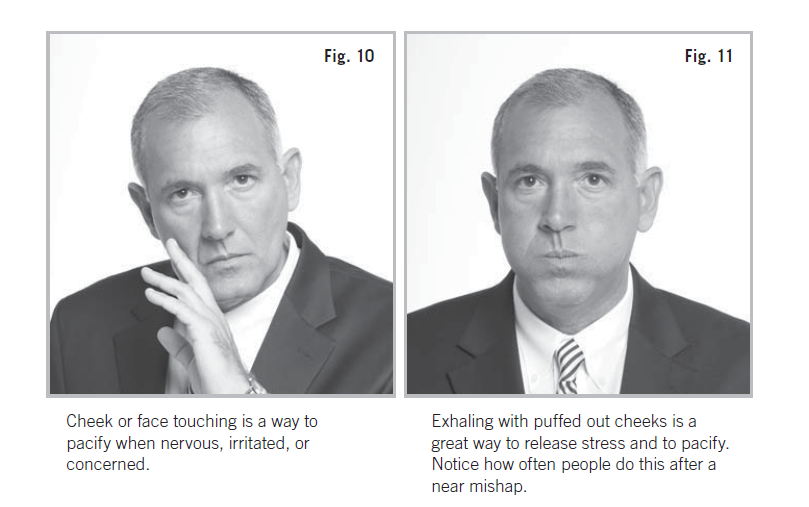

Pacifying behaviors take many forms. When stressed, we might soothe our necks with a gentle massage, stroke our faces, or play with our hair.

If a stressed person is a smoker, he or she will smoke more; if the person chews gum, he or she will chew faster. All these pacifying behaviors satisfy the same requirement of the brain; that is, the brain requires the body to do something that will stimulate nerve endings, releasing calming endorphins in the brain, so that the brain can be soothed.

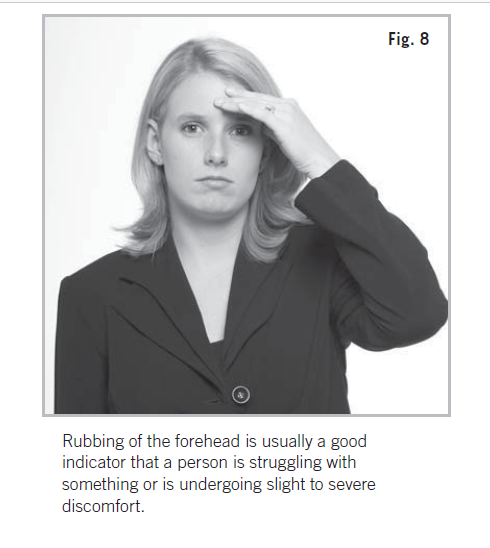

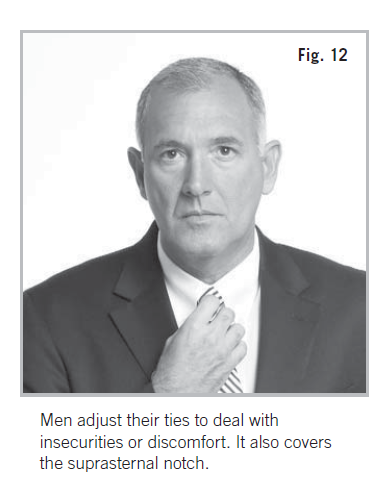

For our purposes, any touching of the face, head, neck, shoulder, arm, hand, or leg in response to a negative stimulus (e.g., a difficult question, an embarrassing situation, or stress as a result of something heard, seen, or thought) is a pacifying behavior. These stroking behaviors don’t help us to solve problems; rather, they help us to remain calm while we do. In other words, they soothe us. Men prefer to touch their faces. Women prefer to touch their necks, clothing, jewelry, arms, and hair. When it comes to pacifiers, people have personal favorites, some choose to chew gum, smoke cigarettes, eat more food, lick their lips, rub their chins, stroke their faces, play with objects (pens, pencils, lipstick, or watches), pull their hair, or scratch their forearms. Sometimes pacification is even more subtle, like a person brushing the front of his shirt or adjusting his tie. He appears simply to be preening himself, but in reality he is calming his nervousness by drawing his arm across his body and giving his hands something to do. These, too, are pacifying behaviors ultimately governed by the limbic system and exhibited in response to stress.

Pacifying Behaviors Involving Sounds

Whistling can be a pacifying behavior. Some people whistle to calm themselves when they are walking in a strange area of a city or down a dark, deserted corridor or road. Some people even talk to themselves in an attempt to pacify during times of stress. I have a friend (as I am sure we all do) who can talk a mile a minute when nervous or upset. Some behaviors combine tactile and auditory pacification, such as the tapping of a pencil or the drumming of fingers.

Excessive Yawning

Sometimes we see individuals under stress yawning excessively. Yawning not only is a form of “taking a deep breath,” but during stress, as the mouth gets dry, a yawn can put pressure on the salivary glands. The stretch of various structures in and around the mouth causes the glands to release moisture into a dry mouth during times of anxiety. In these cases it’s not lack of sleep, but rather stress, that causes the yawning.

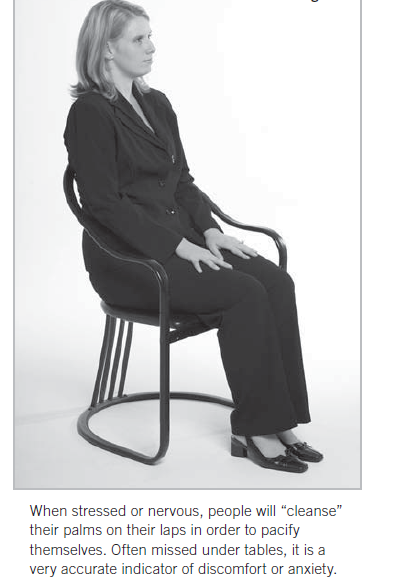

The Leg Cleanser

Leg cleansing is one pacification behavior that often goes unnoticed because it frequently occurs under a desk or table. In this calming or pacifying activity, a person places the hand (or hands) palm down on top of the leg (or legs), and then slides them down the thighs toward the knee. Some individuals will do the “leg cleanser” only once, but often it is done repeatedly or the leg merely is massaged. It may also be done to dry off sweaty palms associated with anxiety, but principally it is to get rid of tension. This nonverbal behavior is worth looking for, because it is a good indication that someone is under stress.

In my experience, I find the leg cleanser to be very significant because it occurs so quickly in reaction to a negative event. I have observed this action for years in cases when suspects are presented with damning evidence, such as pictures of a crime scene with which they are already familiar (guilty knowledge). This cleansing/pacifying behavior accomplishes two things at once. It dries sweaty palms and pacifies through tactile stroking. You can also see it when a seated couple is bothered or interrupted by an unwelcome intruder, or when someone is struggling to remember a name.

An increase in either the number or vigor of leg cleansers is a very good indicator that a question has caused some sort of discomfort for the person, either because he has guilty knowledge, is lying, or because you are getting close to something he does not want to discuss.

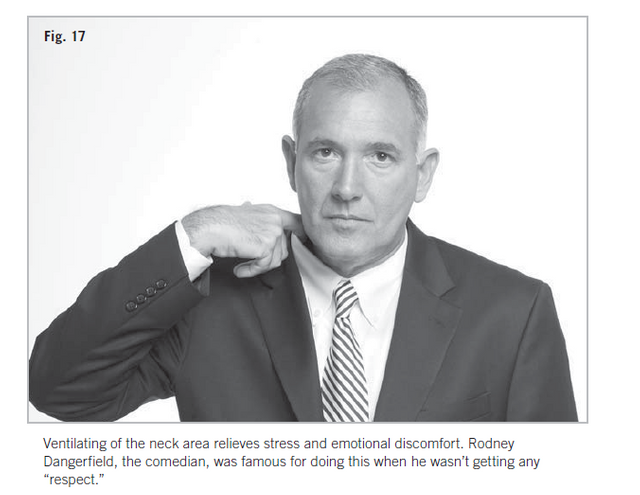

The Ventilator

This behavior involves a person (usually a male) putting his fingers between his shirt collar and neck and pulling the fabric away from his skin. This ventilating action is often a reaction to stress and is a good indicator that the person is unhappy with something he is thinking about or experiencing in his environment. A woman may perform this nonverbal activity more subtly by merely ventilating the front of her blouse or by tossing the back of her hair up in the air to ventilate her neck.

The Self-Administered Body-Hug

When facing stressful circumstances, some individuals will pacify by crossing their arms and rubbing their hands against their shoulders, as if experiencing a chill. Watching a person employ this pacifying behavior is reminiscent of the way a mother hugs a young child. It is a protective and calming action we adopt to pacify ourselves when we want to feel safe. However, if you see a person with his arms crossed in front, leaning forward, and giving you a defiant look, this is not a pacifying behavior!

USING PACIFIERS TO READ PEOPLE MORE EFFECTIVELY

In order to gain knowledge about a person through nonverbal pacifiers, there are a few guidelines you need to follow:

(1) Recognize pacifying behaviors when they occur. I have provided you with all of the major pacifiers. As you make a concerted effort to spot these body signals, they will become increasingly easy to recognize in interactions with other people.

(2) Establish a pacifying baseline for an individual. That way you can note any increase and/or intensity in that person’s pacifying behaviors and react accordingly.

(3) When you see a person make a pacifying gesture, stop and ask yourself, “What caused him to do that?” You know the individual feels uneasy about something. Your job, as a collector of nonverbal intelligence, is to find out what that something is.

(4) Understand that pacifying behaviors almost always are used to calm a person after a stressful event occurs. Thus, as a general principle, you can assume that if an individual is engaged in pacifying behavior, some stressful event or stimulus has preceded it and caused it to happen.

(5) The ability to link a pacifying behavior with the specific stressor that caused it can help you better understand the person with whom you are interacting.

(6) In certain circumstances you can actually say or do something to see if it stresses an individual (as reflected in an increase in pacifying behaviors) to better understand his thoughts and intentions.

(7) Note what part of the body a person pacifies. This is significant, because the higher the stress, the greater the amount of facial or neck stroking is involved.

(8) Remember, the greater the stress or discomfort, the greater the likelihood of pacifying behaviors to follow.

Pacifiers are a great way to assess for comfort and discomfort. In a sense, pacifying behaviors are “supporting players” in our limbic reactions. Yet they reveal much about our emotional state and how we are truly feeling.

The end of the 1st chapter, second chapter THE MOST HONEST PART OF OUR BODY.