Hey Dad… What’s a Whippoorwill?

What’s a Whippoorwill?

There was a night not long ago when I sat out in the yard and realized something was missing. Something I hadn’t noticed was gone until the silence told me. The whippoorwill’s song was gone. So were the bobwhite quail.

Even the crickets seemed more reserved, like they, too, knew something had passed.

I could still hear the wind, but even that seemed confused, rushing past LED-lit warehouse walls instead of rustling through pines and mountain laurels.

The soundscape of my younger days—nightingales, hoot owls, the soft echo of a distant train—was now just the hum of interstate traffic, warehouse construction, and lights that never blink.

We used to play baseball all day in the summer in a field between my best friend’s house and mine. It was small, but the pitcher’s mound was regulation, and a home run meant clearing the telephone wires—only about 100 feet away. Even if the ball cleared the wires, the yellow line in the street was still center field. We could sit on it and wait for a pop fly to come down—because there were hardly any cars, and the few that did come by knew center field belonged to baseball first.

Now, you can’t stand there for five seconds without getting run down by someone who looks like they got their license from a Cracker Jack box.

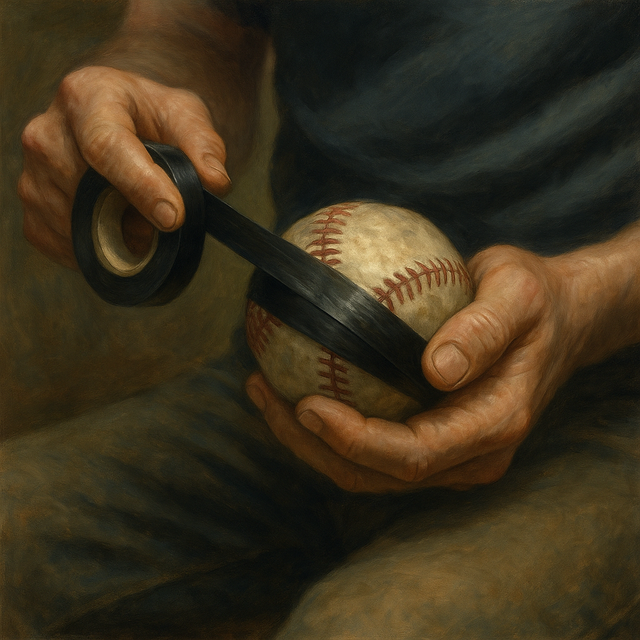

A baseball was a treasure then. There weren’t many places close by to buy one. If we had one, it mattered. When the cover tore off, I’d go into my dad’s toolbox, dig out the black electrical tape, and wrap it tight—Just like he showed me, round and round until the whole thing looked like a lump of coal.

That ball was waterproof. Indestructible. Ugly. Beautiful. It didn’t bounce right, and it sure didn’t fly straight. But it worked. The game must go on!

Have you ever tried to catch a baseball the color of coal when it was thrown straight at you? After the sun went down behind all the trees a half hour before dark?

We had no helmets,

We loved baseball.

We’d toss it high into the air at dusk and try to catch it against a sky still holding onto the last light.

Until the whippoorwill started singing…

That was baseball. That was summer. That was before.

We walked to the lake to fish for pickerel, or catfish, and sometimes sunnies. Got our feet muddy in creeks stained amber from the tannic acid in the leaves. I took my daughters once, years later, out to that same stream way out behind where we played ball—a meandering branch of the Metedeconk River, I believe. Still clear. Still beautiful. Still guarded by skunk cabbage and ghosts of cranberry bogs long since forgotten by the township planners.

The woods were everything. Hundreds of acres behind the houses. They weren’t marked by signs or split rail fences. They just were. They surrounded us, hid deer and secrets, cooled the summer air. They were a playground, a refuge, a cathedral.

And now, they’re going. And in some places… already gone.

You want to see what replaced them?

Look here:

What you’re seeing isn’t just a development. It’s a displacement.

Not development, but colonization—the new gospel of progress. Coming Soon

18,000–95,000 square feet of silence, flickering lights, and trucks—trucks all night long.

And the zoning boards and city commissioners and invaders all seem to agree.

The whippoorwills didn’t leave.

They were evicted.

Do you remember the Lorax?

And I know the people building it didn’t grow up here. They couldn’t have. They can’t smell honeysuckle before they see it. They don’t know the difference between a skunk cabbage and a lily. They never fished for pickerel barefoot or picked huckleberries along a deer trail. They wouldn’t know that the mountain laurels bloom white and pink right before the whippoorwills call.

No, they don’t know it. And worse—they don’t miss it.

There was a trail or road here called Fish Road. It sort of ran east and west along what is now Commodore Highway, which also runs parallel to the interstate and the warehouses. But it was dirt back then, and it wound through the woods, surrounded by mountain laurels. My father told me it was once a Lenni Lenape trail—in fact, one of the last in the area. The township gave it to the developers. They put up a gate and started the bulldozers to help "progress."

When I get the mail now, it’s not letters from neighbors. It’s offers. Slick paper, fake names, LLCs with friendly fonts. Front organizations for developers who want my land— just like they got many of my neighbors’.

But not me. The Family has been here too long. Longer than my memory can reach. To sell would be to betray six or seven generations who fished here, planted here, hunted here, and remembered.

The land I look at—my garden, my patch of high grass— is worth more than anyone can imagine. And not because of money. Because of memory.

I walk in what’s left of those woods still and listen…

And behind that patch of grass now looms something that looks like the invasion of the Borg from Star Trek. It crouches at the edge of the field like an alien machine that swallowed the woods and spit out cinder blocks.

And as I sit in the dusk, thinking all this, my youngest daughter walks up beside me. She leans over, reading something I’ve scribbled on a notepad. A rough draft of a memory. A requiem hymn for a way of life.

She says,

“Uh… hey Dad?”

I turn and smile. “Hey, little one. What’s up?”

She hesitates.

“… What’s a whippoorwill?”

And that—

that is when I feel it:

the sound of something ancient slipping past,

and the ache of knowing

it won’t be heard again.

Whip Poor Will

whipper will

BobWhite

Bob White

“You kind of have to wonder if that’s how the Lenape felt.”