Blessing for the Bar Mitzvah Boy

This is another post that was also written a while back, enjoy:)

When a bar-miṣwah boy gets his aliyah, in many synagogues his father is instructed to say: baroukh shepeṭarannee me`onsho shel zeh - בָּרוּךְ שֶׁפְּטָרַנִּי מֵעָנְשׁוֹ שֶׁל זֶה, or in a free translation: “I acknowledge the Source of all Blessings who has released me from the responsibility (literally the punishment) for the actions of this one(/child).”

This formulation is included in many prayer-books and that it is often amusing for many fathers to feel a relief of sorts that their son is coming of age.

However where does this custom come from?

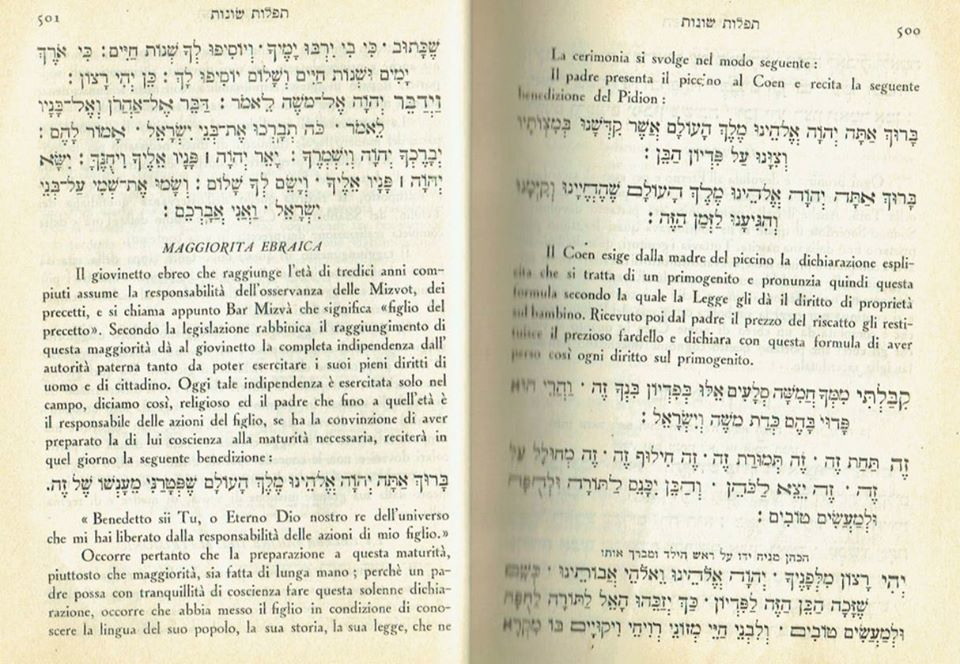

A while back I thought it was mostly an Ashkenazi custom, but recently having looked through a Sepharadee prayer-book from Alexandria, Egypt, I came across not only the formulation mentioned above, but one with God’s name clearly included (p.501 middle of the page):

This turns the formulation into a made-up benediction, without basis in the rabbinic law code, the Babylonian Talmoudh (more about this later).

So where does this formulation come from? Why am I mentioning this now?

In the first aliyah of this week’s portion (Toledoth) we come across this line [1]:

כה,כז וַֽיִּגְדְּלוּ֙ הַנְּעָרִ֔ים וַיְהִ֣י עֵשָׂ֗ו אִ֛ישׁ יֹדֵ֥עַ צַ֖יִד אִ֣ישׁ שָׂדֶ֑ה וְיַֽעֲקֹב֙ אִ֣ישׁ תָּ֔ם יֹשֵׁ֖ב אֹֽהָלִֽים׃

וּרְבִיאוּ, עוּלֵימַיָּא, וַהֲוָה עֵשָׂו גְּבַר נְחַשׁ יִרְכָן, גְּבַר נָפֵיק חֲקַל; וְיַעֲקוֹב גְּבַר שְׁלִים, מְשַׁמֵּישׁ בֵּית אֻלְפָנָא.

27 And the boys grew; and Esau was a cunning hunter, a man of the field; and Jacob was a quiet man, dwelling in tents.

Upon this verse the classical commentaries such as Ibn Ezra/Azra mention that Esau was a deceptive person, and an example of his this behaviour was how he would hunt down animals in a cunning manner. Yaaqobh is presented as the diametric opposite (I add diametric as there are commentaries that mention that Esau originally was considered to have the merit to marry Le’ah, but through his actions and insistence on living a false life, Le’ah was then married to Yaaqobh) for he was a tent dweller and a wise scholar.

The more allegorical Midrash Rabbah discusses this verse, and this is the source for this formulation [2 (emendations in text are mine)]:

י וַיִּגְדְּלוּ הַנְּעָרִים (בראשית כה, כז), רִבִּי לֵוִי אָמַר מָשָׁל לַהֲדַס וְעִצְבוֹנִית שֶׁהָיוּ גְּדֵלִים זֶה עַל גַּבֵּי זֶה, וְכֵיוָן שֶׁהִגְדִּילוּ וְהִפְרִיחוּ זֶה נוֹתֵן רֵיחוֹ וְזֶה חוֹחוֹ, כָּךְ כָּל י"ג שָׁנָה שְׁנֵיהֶם הוֹלְכִים לְבֵית הַסֵּפֶר וּשְׁנֵיהֶם בָּאִים מִבֵּית הַסֵּפֶר, לְאַחַר י"ג שָׁנָה זֶה הָיָה הוֹלֵךְ לְבָתֵּי מִדְרָשׁוֹת וְזֶה הָיָה הוֹלֵךְ לְבָתֵּי עֲבוֹדַת כּוֹכָבִים. אָמַר רִבִּי אֶלְעָזָר צָרִיךְ אָדָם לְהִטָּפֵל בִּבְנוֹ עַד י"ג שָׁנָה, מִכָּן וָאֵילָךְ צָרִיךְ שֶׁיֹּאמַר בָּרוּךְ שֶׁפְּטָרַנִּי מֵעָנְשׁוֹ שֶׁל זֶה....

And the youths (‘Esau and Yaaqobh) matured, Ribbi Lewee said that this is a metaphor for a Myrtle and a Ruscus bush that were growing on top of each other, and as they matured and blossomed one produced its aroma and one produced its thorns, such that for 13 years they would both go to school and both would return from school, after 13 years one would go to the halls of study (Yaaqobh) and one would go to the houses of idol worship (Esau). Said Ribbi ‘Elazar a man needs to accompany/supervise his son until 13 years of age, from here on in he should say “I acknowledge The Source of all Blessings who has released me from the responsibility (literally the punishment) for the actions of this one(/child).”

Now that we know the when and where, we can agree (I hope) with the midrash here that clearly it indicates that it should be the hope of every father that his son grow up to be a wise man, rather than a deceptive one, and that he should acknowledge and be thankful that his son has made it to adulthood.

Interestingly, the text of this midrash is from the sixth century of the common era, or by our reckoning from around 4350 [3], long before any Jews would have self-identified as Sepharadee or ‘Ashkenazee.

However, the midrashic statement there is not a formalised instruction as to when exactly to mention this, but rather a general piece of advice. Now let’s look at some other sources dealing with this matter, starting with the most commonly used restatement of law, R Yoseph Karo’s [4] Shulḥan Aroukh [5] (I mention this later source as I have not yet located a source for this custom in Maimonides’ restatement, the Mishneh Torah) [6][7]:

מִי שֶׁלֹּא רָאָה אֶת חֲבֵרוֹ מֵעוֹלָם, וְשָׁלַח לוֹ כְּתָבִים, אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁהוּא נֶהֱנֶה בִּרְאִיָּתוֹ אֵינוֹ מְבָרֵךְ עַל רְאִיָּתוֹ. הַגָּה: יֵשׁ אוֹמְרִים מִי שֶׁנַּעֲשֶׂה בְּנוֹ בַּר מִצְוָה, יְבָרֵךְ: בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה' אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם שֶׁפְּטָרַנִי מֵעָנְשׁוֹ שֶׁל זֶה (מַהֲרִי''ל בְּשֵׁם מָרְדְּכַי וּבְר''ר פ' תּוֹלְדוֹת), וְטוֹב לְבָרֵךְ בְּלֹא שֵׁם וּמַלְכוּת (דַּעַת עַצְמוֹ).

One who has not ever seen his friend, and has had correspondence with him, even when s/he does see her/him, s/he does not recite the benediction with regards to seeing her/him.

Gloss (of R Mosheh Isserles [8]): There are those who say that when his son has reached the age of bar-miṣwah, one should recite the benediction: “I acknowledge The Source of all Blessings, Lord of the Universe, who has released me from the responsibility for the actions of this one” (The Maharil (Yaaqobh ben Mosheh Lewee Moelin Segal [9]) in the name of the Mordokhay, and in Beresheeth Rabbah Perashath Toledhoth), and it is best to recite this benediction without mentioning God’s name (i.e. Lord of the Universe - “אַתָּה ה' אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם”).

The reasoning behind R Mosheh Isserles’ recommendation to not recite the benediction relates to it not being a benediction that is mentioned in the Babylonian Talmoudh; this is similar to the commonly said post-Talmoudhic benediction: hannothen layyaeph kowaḥ (הנותן ליעף כח) who gives strength to the weary. The latter becomes an issue for people who care about fulfilling both the written and oral (Rabbinic) law, as reciting a benediction not authorised by the rabbis, is considered as a berakhah lebhaṭalah (ברכה לבטלה) a wasted benediction, and is a transgression of the commandment to not take the Lord’s name in vain [10].

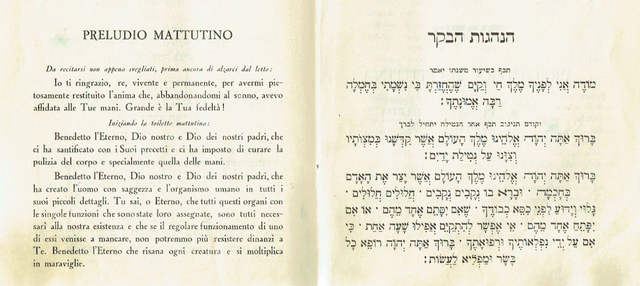

All said and done, why had the Sepharadee siddour of Alexandria included the benediction in this format. At first I thought perhaps it may have been R Prato’s Italian background that may have had an influence in including this benediction; there is an Italian influence in the rather unique wording used in the benediction that one says after a successful visit to the lavatory, see scan of page below:

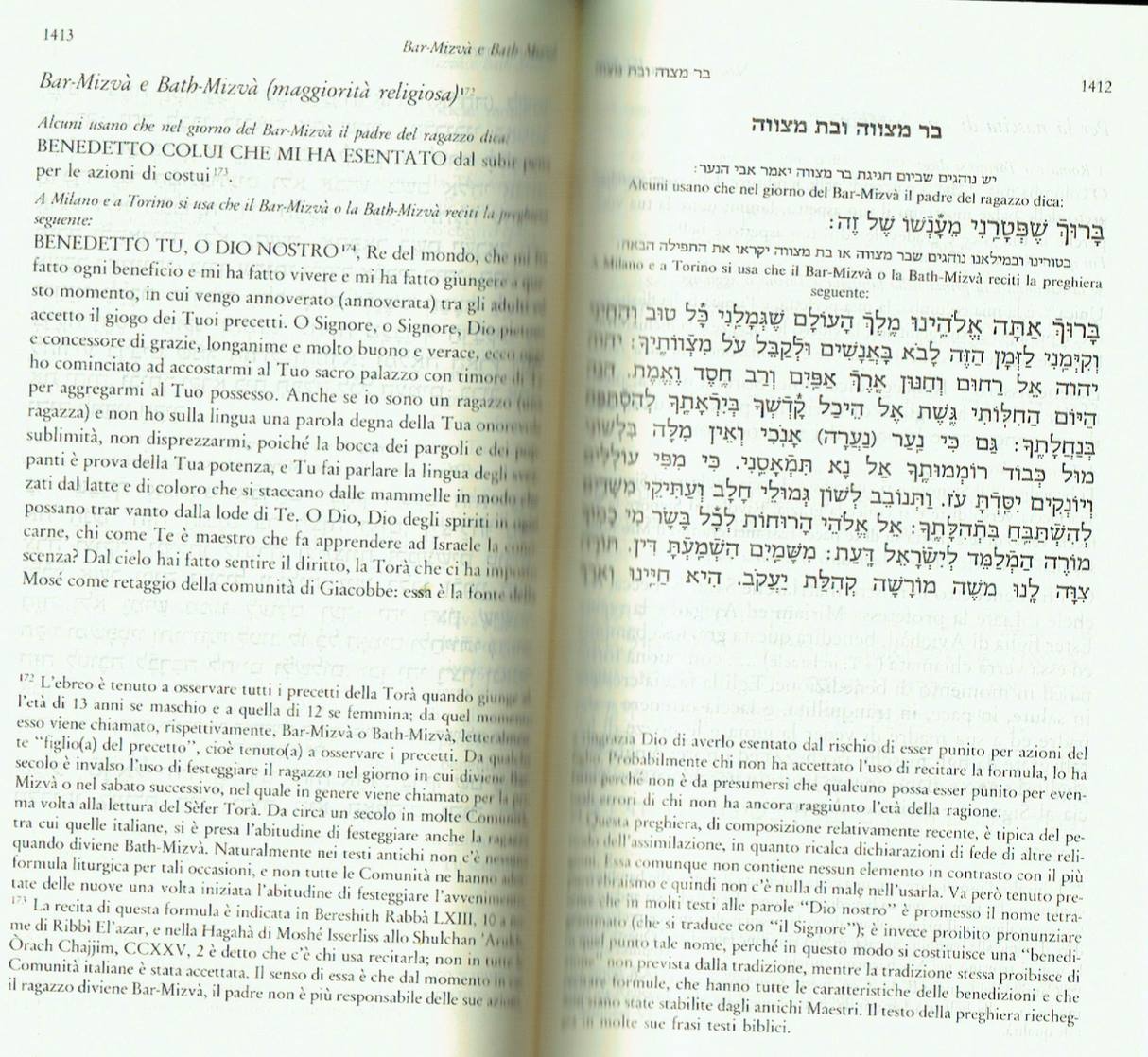

However upon checking the most comprehensive Italian Rite prayer book by Menachem Emanuelle Artom [11], which deals with the customs of the bigger communities of Rome/Roma, Milan/Milano, Turin/Torino and Jerusalem/Gerusalemme, one sees that the Italian communities accepted R Mosheh Isserles’ advice, to say the benediction without the Lord’s name in it. That said, quite amusingly, the communities of Milan and Turin complicated their lives by inventing a different made-up benediction to follow the recital of baroukh shepeṭarannee, see scan of page below:

It is still possible to mention that there is an Italian influence, in terms of saying the full baroukh shepeṭarannee with the Lord’s name included, as perhaps the Italian communities only agreed to follow R Mosheh Isserles’ advice at a later stage, and at the time of publication (5695 or 1935 CE) of the Alexandrian prayer book, R Prato was still of the opinion to say the blessing in full, but this would require further investigation.

Thus far, we can conclude that the baroukh shepeṭarannee formulation is ancient and not peculiar to any specific prayer rite, and that saying it in full is most likely of ‘Ashkenazee origin. Why the Alexandrian community adopted the full-form benediction could possibly be explained by changes in attitude to how the law was to be followed; for a while the communities of Egypt followed Maimonides’ approach to law, later they followed R Dawidh ibn Zimra’ and his student R Castro [12], so that later they started following other rabbinic figures, again this would require further investigation. There is perhaps also the possibility that what was printed in the prayer book was not necessarily strictly followed by anyone (e.g. Artscroll publications).

Another opinion on the matter is that of R `Obhadiyah Yoseph [13], who agrees with R Mosheh Isserles’ reasoning to not say the full benediction, but quotes the Ben ‘Ish Ḥai’s opinion, that one should have in mind/heart to have said the benediction in full, but to not actually utter it [14].

In R Isaac d’ Gillette's extensive article [15] he mentions other opinions on the matter:

- The young man be saying baroukh shepeṭarannee acknowledging that he is not liable for the punishment due to his father

- Both the father and young man be saying it to absolve each other

- A father should be saying it for his daughter who has come of age (R `Obhadiyah Yoseph agrees with the original source to follow this practice).

As can be seen there is more than meets the eye with regards to this custom.

I will end by saying that a more amusing usage of this formulation is to say it with regards to the people which one is annoyed by or does not get along.

Wishing all a Shabbath Shalom and a belated Ḥodhesh Ṭobh (a good month, both Hebrew and secular, Kislew and December, which started yesterday) in which we all merit to walk in the ways of Jacob.

=======

Footnotes

=======

[1] http://www.mechon-mamre.org/c/ct/cu0106.htm and

http://www.mechon-mamre.org/p/pt/pt0125.htm

.

[2] http://www.ateret4u.com/online/f_01633_part_6.html

.

[3] https://he.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D7%9E%D7%93%D7%A8%D7%A9_%D7%A8%D7%91%D7%94

.

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_ben_Ephraim_Karo

.

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shulchan_Aruch

.

[6] http://www.sefaria.org/Shulchan_Arukh,Orach_Chayim.225?lang=en

.

[7] Of parenthetical note, is the rather memorable placement, in terms of topical association, of this instruction and gloss between an instruction to not recite the benediction sheheḥeyanou - שֶׁהֶחֱיָנוּ (acknowledging God for sustaining our life until this moment), with regards to a friend one has not seen but has been corresponding with by mail, and the following instruction to recite a benediction for a seasonal fruit, even if this fruit is sighted in a friend’s hand or on a tree.

.

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moses_Isserles

.

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yaakov_ben_Moshe_Levi_Moelin

.

[10] http://www.mechon-mamre.org/p/pt/pt0220.htm#6

.

[11] http://www.torah.it/artom.pdf

.

[12] http://www.yeshiva.org.il/wiki/index.php?title=%D7%A8%D7%91%D7%99%D7%93%D7%95%D7%93_%D7%91%D7%9F_%D7%96%D7%9E%D7%A8%D7%90

רבי אברהם הלוי (בעל שו"ת גינת ורדים) כותב, כי במצרים נהגו כפי פסקי הרדב"ז ומהר"י קאשטרו תלמידו, אפילו כאשר הם כנגד שיטת הרמב"ם (גינת ורדים חו"מ ג).

.

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ovadia_Yosef

.

[14] http://halachayomit.co.il/he/ReadHalacha.aspx?HalachaID=2202

.

[15]

http://www.daat.ac.il/daat/kitveyet/sinay/baruh-2.htm

אולם מצאנו שר' מרדכי הכהן, מתלמידי ר' ישראל די קוראל )מגורי האר"י( בספרו שפתי כהן

על התורה לפרשת לך לך, וונציה שס"ה, דף יג ע"ב )ווארשא 1881, עמ' טז(, אכן סובר שהבן

מברך ברוך שפטרני. על הכתוב "לך לך מארצך וממולדתך ומבית אביך" )בראשית, יב, א(

נאמר בשפתי כהן: "הוא אחר יג שנה, שהבן מברך: ברוך שפטרני מעונשו של אבא".

===

ובספר "נתיבי עם" לר' עמרם אבורביע )רב העיר פתח תקווה בשנים תשי"א-תשכ"ז( בחלק

המנהגים וההלכות, סימן רכה ס"ק ב', עמ' קל, הוא מוסיף על דברי הרמ"א בשולחן ערוך: מי

שנעשה בנו בר מצווה מברך וכו'. "הבאר היטב כתב שני פרושים. עיין שם. ושעל כן נהגו לברך

גם שניהם האב והבן".

====

אולם כבר ר' יוסף תאומים, בעל פרי מגדים, מגדולי הפוסקים במאה השמונה עשרה, תמה

באו"ח שם ס"ק ה: למה לא יברך בנקבה, הרי הבנים הקטנים, הנענשים בשביל עוונות האב,

ובגלל זה, לדעת הלבוש, מברך האב ברוך שפטרני )עיין לעיל(, לא שנא זכרים ונקבות? כיוצא

בו שואל ר' יעקב צבי שפירא, מחכמי התורה במאה התשע עשרה בספרו טהרת השולחן,

ווילנא תרס"א:

"צריך עיון לפי זה )"דעד עתה נענש האב כשחטא הבן בשביל שלא חנכו"( גם בבתו

יברך, דמחויב לחנך בתו... ומכל שכן לטעם הלבוש, הא גם בנותיו נענשים".

===

וכן דעת הרב עובדיה יוסף הראשון לציון, לשעבר רבה של ארץ ישראל, ביביע אומר, חלק ו

סימן כט, ירושלים תשל"ו, עמ' צח, וזה לשונו:

"ולפי מה שכתבתי אין הכי נמי, שמברך גם על בתו ובפרט שהעיקר לברך ברכה זו בלי

שם ומלכות. אם כן אין כל חדש לאמרה גם לגבי בת שהגיעה למצוות. ולית דין צריך

בשש".