I materiali dell'Architettura: I materiali metallici - Quarta Parte// Materials of Architecture: Metallic materials - Fourth Part [ITA - ENG]

CCO Creative Commons Torre Eiffel, Parigi

l’altro giorno ci siamo salutati parlando del profondo dualismo tra la figura dell’architetto e quella dell’ingegnere, di come il progresso in ambito tecnico abbia fatto prevalere quest’ultima figura sulla scena internazionale. Ma se l’ultima volta ci siamo concentrati sul ruolo dell’ingegneria, oggi vediamo, invece, quali sono stati gli sviluppi della disciplina dell’architettura che, inevitabilmente, si trova a fare i conti con l’inarrestabile progresso tecnico a fronte della profonda natura estetica ed artistica che l’ha sempre contraddistinta.

Ebbene, soprattutto il XIX e i XX secolo rappresentano anni di grande mutazione per l’architettura, che continua a modellare e modificare la propria immagine a seconda delle esigenze culturali, estetiche ma anche tecnologiche di quel periodo e, ovviamente, in tal senso ebbero un ruolo fondamentale i metalli ferrosi… ma non voglio anticipare altro perciò, amici, buon proseguimento di lettura!

I MUTAMENTI DELL’ARCHITETTURA NEL CONTESTO EUROPEO TRA XVIII E XIX SECOLO

Come abbiamo detto precedentemente, il continuo progresso tecnologico e la conseguente affermazione dell’ingegneria ha portato l’architettura a rivedere le proprie concezioni artistiche, strutturali ed estetiche grazie alle nuove forme e tecniche che i materiali ferrosi potevano offrire alle opere di quegli anni.

Già dal XVIII secolo, in realtà, con la Rivoluzione Industriale, si fa strada un nuovo modo di concepire l’architettura, e uno dei primi aspetti che vengono messi in discussione sono le decorazioni e dunque le caratteristiche riguardanti l’estetica che la nuova architettura debba avere: in questo clima, grazie anche al progresso nel settore archeologico che permette, per la prima volta, di conoscere dettagliatamente i monumenti delle antiche civiltà mediterranee, si cerca di rinnovare profondamente il modo di progettare ricorrendo ad una reinterpretazione proprio delle forme classiche della tradizione greca e romana, dando origine al cosiddetto neoclassicismo.

Le nuove tecnologie a disposizione si sposano perfettamente allo scopo, infatti travi e pilastri in ferro sono visti come i naturali e moderni eredi di quelle che erano colonna e architrave degli antichi ordini architettonici. Questa rilettura del periodo classico perde interesse fra i progettisti nella prima metà dell’800, che spostano l’attenzione anche sugli atri importanti stili del passato dando vita, in maniera analoga, al neogotico, neo-romanico, neo-bizantino, e così via.

Su questo tema delle innovazioni delle forme e delle strutture, in effetti, esistono due differenti correnti di pensiero in contrapposizione fra loro: da una parte c’è chi considera che le maggiori evoluzioni stilistiche siano diretta conseguenza dell’innovazione di nuovi materiali o dei metodi di costruzione, dall’altra, invece, c’è chi sostiene che le innovazioni tecnologiche siano il frutto dell’adeguamento alle nuove intenzioni estetiche e alla nuova visione del mondo.

Chiaramente, lo sviluppo dell’architettura moderna è figlio di una verità che si trova in entrambi i modi di pensare pocanzi descritti. A livello mondiale, date le diverse condizioni sociali, economiche e culturali, non permisero un comune percorso di sviluppo: le fasi pionieristiche di questo movimento presero, infatti, diverse strade ma con il comune allontanamento dalle forme del passato ormai superate.

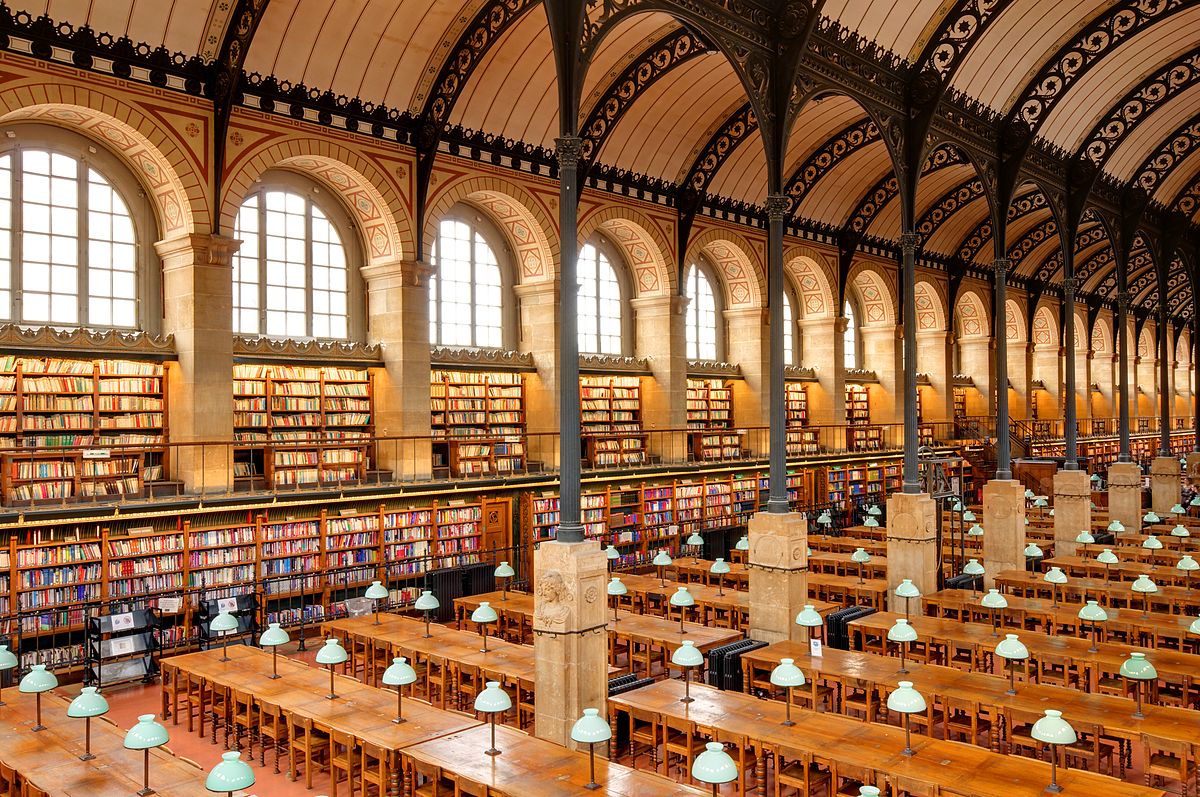

Intorno alla metà dell’800 il celebre architetto francese Henri Labrouste, che contribuì fortemente a questa tendenza innovatrice dell’architettura, progettò due opere di grande interesse: la Biblioteca di St. Genevieve e la Biblioteca imperiale. Entrambe le strutture sono realizzate in ghisa, ottenendo spazi notevolmente ampi e funzionali, ma sono anche caratterizzate dall’avere gli spazi interni racchiusi da un imponente ed estremamente decorato involucro in pietra.

Ed è sull’onda di questa voglia di cambiamento che, attorno alla fine del XIX secolo, in Europa, si sviluppa il fenomeno artistico denominato Art Nouveau. Il Paese in cui ebbe origine questo movimento è il Belgio e uno dei suoi protagonisti più importanti fu l’architetto belga Victor Horta.

Una celebre opera del suddetto architetto, emblema del ricercato connubio tra struttura e decorazione, è la Casa del Popolo, costruita a Bruxelles nel 1986. Quell’obiettivo viene raggiunto grazie al fatto che gli elementi strutturali divennero essi stessi elementi decorativi dell’edificio.

L’art nouveau riuscì a reinterpretare i materiali ferrosi anche dal punto di vista meramente decorativo e un esempio lampante di ciò è dato da Hector Guimard, il quale riuscì a lavorare la ghisa ottenendo forme sinuose che richiamavano gigantesche forme vegetali, e li ritroviamo negli accessi alle metropolitane parigine.

L’Art Nouveau, che continuò a silupparsi fino agli anni a cavallo tra il XIX e il XX secolo, non si limita solo ai materiali ferrosi o alle costruzioni in generale, bensì, trova consenso anche nella grafica, nel disegno industriale, nell’artigianato del vetro, nel disegno di mobili, nel disegno di gioielli e nella moda.

Se in Europa, con l’Art Nouveau, uno degli elementi predominanti è l’aspetto decorativo, in America, invece, c’è una volontà di eliminare gran parte di questa veste decorativa di carattere storico ed è in questo contesto che architetti ed ingegneri lavorano fianco a fianco per la ricostruzione del centro di Chicago… ma questa, miei cari lettori, è un’altra storia.

E così anche per oggi siamo giunti al termine del nostro viaggio e a me non resta che, al solito, darvi appuntamento al prossimo articolo per conoscere, laddove lo vogliate, gli sviluppi della nostra avventura nel mondo dei materiali da costruzione. Ma prima, e concludo, come sempre vi ringrazio per avermi letto e, come ormai ben sapete, mi auguro abbiate gradito la lettura… alla prossima, vi abbraccio tutti!

L'Ego dice: "Quando ogni cosa andrà a posto troverò la pace".

Lo Spirito dice: "Trova la pace e ogni cosa andrà a posto".

CCO Creative Commons Biblioteca di St Geneviev

the other day we said goodbye talking about the profound dualism between the figure of the architect and that of the engineer, of how progress in the technical field has made this latter figure prevail on the international scene. But if the last time we focused on the role of engineering, today we see, instead, what were the developments of the discipline of architecture that, inevitably, is to deal with the unstoppable technical progress in the face of deep aesthetic and artistic nature that has always distinguished it.

Well, especially the nineteenth and twentieth century are years of great change for architecture, which continues to shape and modify its image according to the cultural, aesthetic and technological needs of that period and, of course, in this sense played a role fundamental ferrous metals... but I do not want to anticipate any more, therefore, my friends, a good continuation of reading!

THE CHANGES OF ARCHITECTURE IN THE EUROPEAN CONTEXT BETWEEN THE XVIII AND XIX CENTURIES

As we said previously, the continuous technological progress and the consequent affirmation of engineering has led the architecture to review its artistic, structural and aesthetic concepts thanks to the new forms and techniques that ferrous materials could offer to the works of those years.

Already in the eighteenth century, in reality, with the Industrial Revolution, a new way of conceiving architecture is making its way, and one of the first aspects that are put into question are the decorations and therefore the characteristics concerning the aesthetics that the new architecture should have: in this climate, thanks also to the progress in the archaeological sector that allows, for the first time, to know in detail the monuments of the ancient Mediterranean civilizations, we try to deeply renew the way to design using a reinterpretation of the classical forms of the Greek and Roman tradition, giving rise to the so-called neoclassicism.

The new technologies available are perfectly matched to the purpose, in fact beams and iron pillars are seen as the natural and modern heirs of those who were the column and architrave of the ancient architectural orders. This reinterpretation of the classical period loses interest among the designers in the first half of the nineteenth century, which shift the attention also on the other important styles of the past giving life, in a similar way, to the neo-Gothic, neo-Romanic, neo-Byzantine, and so on.

On this theme of the innovations of forms and structures, in fact, there are two different currents of thought in opposition to each other: on the one hand there are those who consider that the major stylistic evolutions are a direct consequence of the innovation of new materials or methods on the other hand, on the other hand, there are those who maintain that technological innovations are the fruit of the adaptation to new aesthetic intentions and to the new vision of the world.

Clearly, the development of modern architecture is the son of a truth that is found in both the ways of thinking described above. At the global level, given the different social, economic and cultural conditions, they did not allow a common development path: the pioneering phases of this movement took, in fact, different paths but with the common removal from the past outdated forms of the past.

Around the mid 800's the famous French architect Henri Labrouste, who contributed strongly to this innovative trend of architecture, designed two works of great interest: the Library of St. Genevieve and the Imperial Library. Both structures are made of cast iron, obtaining considerably large and functional spaces, but they are also characterized by having the internal spaces enclosed by an imposing and extremely decorated stone casing.

And it is on the wave of this desire for change that, around the end of the nineteenth century, in Europe, the artistic phenomenon developed called Art Nouveau. The country in which this movement originated is Belgium and one of its most important protagonists was the Belgian architect Victor Horta.

A famous work by the aforementioned architect, emblem of the refined combination of structure and decoration, is the House of the People, built in Brussels in 1986. That goal is achieved thanks to the fact that the structural elements themselves became decorative elements of the building.

The art nouveau succeeded in reinterpreting the ferrous materials also from the merely decorative point of view and a striking example of this is given by Hector Guimard, who managed to work the cast iron obtaining sinuous shapes that recalled gigantic vegetal forms , and we find them in the accesses to the subways in Paris.

The Art Nouveau, which continued to flourish until the years between the nineteenth and twentieth century, is not limited only to ferrous materials or constructions in general, but also finds consensus in graphics, industrial design, craftsmanship of glass, furniture design, jewelry design and fashion.

If in Europe, with the Art Nouveau, one of the predominant elements is the decorative aspect, in America, however, there is a desire to eliminate much of this decorative garment of historical character and it is in this context that architects and engineers they work side by side for the reconstruction of downtown Chicago... but this, my dear readers, is another story.

And so for today we have come to the end of our journey and I just have to give you an appointment to the next article to know, where you want it, the developments of our adventure in the world of building materials. But first, and I conclude, as always, I thank you for reading and, as you well know, I wish you enjoyed reading... see you next time, I embrace you all!

The ego says: "When everything goes right I will find peace"

The Spirit says: "Find peace and everything will fall into place"

CCO Creative Commons Accesso alla metropolitana, Parigi

Le mie fonti...

-Appunti delle lezioni e dei seminari universitari

-William J. R. Curtis, L'architettura moderna dal 1900, Phaidon

-La collana di libri di G.K.Koening-F.Brunetti, Corso di Tecnologia delle Costruzioni , Le Monnier

Amazing post! I love it. Hey UPVOTE my post: https://steemit.com/life/@cryptopaparazzi/chapter-one-let-there-be-the-man-and-there-was-a-man-let-there-be-a-woman-and-there-was-sex and FOLLOW ME and I ll do the same :)