Innovation In The Games Industry: What Role Does It Play?

Hey I thought I'd share my Thesis I wrote at Uni many years back! As its over 64kb, it will be split over 3 posts! It has taken much more time than I thought neccessary to post even this first Chapter! The original file was written in word, and preserving formatting, images etc so it nice to read here, using markdown has been complicated! Its my first shot at it, hope it goes well! Any upvotes and comments are appreciated!

Navigation:

(click the text below to navigate the the document)

++Chapter 1 (Innovation in General)++

++Chapter 2 (Innovation & the Games Industry)++

++Chapter 3 Investigation, Data Analysis and Conclusions, Recommendations and Conclusion++

Innovation In The Games Industry: What Role Does It Play?

Introduction

This essay sets about finding out what role innovation plays in industries and games industry to find methods, variables and limitations associated with innovation. This will eventually lead to empirical research to test the hypothesis:

‘Game ideas with more innovation sell better, than ones with less’.

Throughout the dissertation and in the conclusion, the combination of research into innovation's role in the industry, and the empirical research results will lead to the clarification of the industrial situations required to sell an innovative game more successfully.

Chapter 1

Drucker, (1993) as cited in (Berkun 2007, p.15) “Successful entrepreneurs do not wait until "the Muse kisses them" and gives them a "bright idea"; they go to work. Altogether, they do not look for the "biggie," the innovation that will "revolutionize the industry," create a "billion-dollar business," or "make one rich overnight." Those entrepreneurs who start out with the idea that they'll make it big — and in a hurry — can be guaranteed failure. They are almost bound to do the wrong things. An innovation that looks very big may turn out to be nothing but technical virtuosity, and innovation with modest intellectual pretensions; a McDonald’s, for instance, may turn into gigantic, highly profitable businesses.”

In order to make any educated judgements about innovation, in this chapter, I discuss the meanings, diffusion, processes, cycles, organizational aspects, economy and risks of innovation. This will throw light on the methods, variables and limitations associated with innovation.

Innovation in General

Establishing what innovation actually means will help delineate the boundaries of the meaning of the word. Thompson (1992, p.456) states that innovation is to “…bring in new methods, ideas, etc.; make changes.” This is too broad a definition for this study and describes the process of innovation, whereas, the newer definition from Ask Oxford (2008) reads, “…1 the action or process of innovating. 2 a new method, idea, product, etc.” describes the process and a finished innovation.

Importantly, Fagerberg (2006, P.4) distinguishes between innovation and invention. Innovation is the implementation of an invention, or new idea. Invention requires creative ability, whereas innovation relies on other resources to turn an invention into an innovation. Fagerberg’s (2006, p.4) deeper meaning describes this process from, invention, through production and commercial success, as innovation, which is more appropriate to industry. An innovative game idea is just the beginning of the process of innovation, but creating this idea does require invention.

At the other end of the process, industrial “…examples of innovation[s] [are:] …new products, new methods of production, new sources of supply, the exploitation of new markets, and new ways to organize business…[and]…new combinations of existing resources.” (Box 1.2 The innovation theorist Joseph Schumpeter 1883-1950 cited in Fagerberg 2006, p.6). Therefore, in order to be classed as innovative, the end product must not only be ‘new’, but as important, is the process a product passes through to be termed innovative.

The introduction of new ideas is not as easy as it sounds, but in order for it to be accepted, it has to “diffuse”. Diffusion describes the process whereby, a single innovation starts off in use by a minority, which is then previeved by the majority as an improvement, and therefore, the innovation spreads and develops across the majority, till it has completely diffused (Hall 2006, p.259). Though, before an innovation becomes the norm, “it will be questioned relentlessly.” Innovators believe, by looking back at past innovations and their masters, entrepreneurs assume ‘heroic’ treatment. Until the “innovation is accepted”, the road to acceptance, is not so much a straight line, but filled with resistance (Berkun 2007, p.59).

“Many technologists think that advantageous innovations will sell themselves, that the obvious benefits of a new idea will be widely realized by potential adopters, and that the innovation will therefore diffuse rapidly. Unfortunately, this is very seldom the case. Most innovations in fact diffuse at a surprisingly slow rate” (Rogers, 2003 cited in Berkun, 2007, p.64), a point echoed by Hall (2006, p.479). This may be because an invention may not be realised till it has commercial viability, or it may rely on further improvements or innovations to succeed, which makes for a delay from invention to innovation. “…[W]e think…a single innovation is often the result of a lengthy process involving many interrelated innovations” (Fagerberg 2006, pp.5-6).

Hall (2006, pp.473-475) explains that in the Information and Technology sector the cost of adapting and absorbing new ideas slows down rates of diffusion and profit. This could be due to the non-cooperative attitude to some innovations, which meet resistance in finding aid, as some businesses feel threatened by the innovation Schumpeter (1934, p.87). Therefore, the beginning of the innovative process may be slow, requiring an unrelenting, persuasive attitude when faced with these hurdles of diffusion, making clear the ‘commercial viability’ of a product may speed up the process.

Diffusion of an innovation can lead to the improvement of it, by others. This may explain the claim from Schumpeter, (1939) as cited in Fagerberg (2006, p.6), that innovations tend to “’cluster’ in certain industries and time periods.” Hall (2006, pp.461-473) states that of course, this is encouraged by Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs), which is a catalyst in the process of innovation. Granstrand (2006, p.266) endorses this belief, declaring that “[t]he use of property-like rights to induce innovations of various kinds is perhaps the oldest institutional arrangement that is particular to innovation as a social phenomenon.” But, conversely, Granstrand (2006, pp.284-285) concludes that, “surprisingly little scholarly attention has been devoted to the study of intellectual property rights and innovation.” This highlights how fickle these claims could be, but the truth of the matter is, a direct copy of a product for commercial exploitation is restricted by IPRs, which means the product has to be changed in some way, whether it be for the better or worse, thus some successfully innovate, and others fail.

Technological innovation requires risk takers, “real pioneers take the bulk of the risks related to the introduction of new knowledge and bear most of the costs. In effect, they are living experiments from which their immediate successors vulturously benefit.” Firms often copy and improve upon inventions, where profitable, “[t]hose entrepreneurs who follow up an original invention are able to stake the most comprehensive patent claims and hence corner the lion’s share of the new market. (Fuller 2001, p.xii). Whether or not one decides to improve an already existing project, or create a totally original one, in all cases, IPRs are an important variable in the process of innovation (more on IPRs in Chapter 2).

The industrial processes of innovation is widely written about, here are the popular methodological understandings of the processes. Kline & Rosenberg, (1986) as cited in Fagerberg (2006, pp.8-9) describe a “linear model” which can be used to class innovation, but they also argued it could not describe every innovation. It was based upon the idea that innovation happened in stages, “[r]esearch (science) comes first, then development, and finally production and marketing”, Pavitt (2006, p.88) agrees.

Kline & Rosenberg, (1986) as cited in Fagerberg (2006, pp.8-9) state that not all innovations come from scientific breakthrough, more true for game ideas. “Firms normally innovate because they believe there is a commercial need for it, and they commonly start by reviewing and combining existing knowledge. It is only if this does not work, they argue, that firms consider investing in research (science).” This sounds familiar in the games industry, as each generation of new console fills the shelves to fortify the diversity of innovations available to the market, and there is a tendency to combine existing games to create new ones, or indeed the combination of existing games with new hardware to elicit new gameplay experiences.

Innovative game’s may require new code, or even new hardware to make the game possible, this part of production is best suited to Pavitt’s (2006, pp.89-90) description of the relationship between the first two stages of innovation. Research and development laboratories aid in the production of knowledge, small firms are developed to improve upon this knowledge for “commercial exploitation” and private and public knowledge is developed by universities and “business firms”, who develop and apply knowledge, which means that the second stage of development benefits from innovative knowledge produced in the first stage, because they have the capacity to implement the ideas. The last stage of the process determines if the project was innovative or not, as the consumer’s unpredictable shopping habits decides whether or not it is a success.

A successful innovative product may only stay successful for a limited time. Once success is achieved, in a business environment, the path that lead there, gets followed again and again, problematically so; as IBM knows, to stay the top, new paths to success have to be discovered (Farson & Keyes 2003, pp.56-57). This cycle shows that a limitation of innovation is the time it can remain successful, Schumpeter (1934, p.134) outlines an example where the combination of existing factors or means of production may provide profit, by combining the same product, with a cheaper source of supply, even whilst keeping prices the same, but not for long, as “the competition which steams after”, in an entrepreneurial pursuit, will make this source of revenue, short lived.

Kelley & Littman (2004, pp.226-227) give an example of how IDEO (2008a) kept innovation in their grasp by making sure they continually changed their paths to success. The example is that after winning the “Sandhill Challenge” (a car-racing challenge) “two years running”, IDEO remembered after all, a “creative outlet” where, even the production of ‘home-made’ race cars can become routinized, routine being the “enemy of innovation”, they stuck to the “IDEO way” and “entered a beautiful red Chinese dragon mounted on three engineless motorcycles, and won the ‘whimsical’ category.” This suggests that changing routine keeps up with the cycles of innovation, that success is not continuous; a business has to constantly change and adapt to the world around it to stay afloat (Farson & Keyes 2003, pp.72-74).

Kuhn (1996, p.52) states that like the cycles of innovation, there are similar patterns found in the business of science. “Normal science” is described as a “puzzle-solving activity”, effective at achieving its aim, and adding to knowledge. However, it “does not aim at novelties of fact or theory, and when successful, finds none.”, but, scientific research has been shown to discover “new and unsuspected phenomena”. This by-product, or anomaly that normal science spurs, is corroborated by history itself, which confirms its ability to produce “surprise” discoveries. The anomalous results that scientific research creates, contributes to a “paradigm change”, where new, scientifically proven knowledge is incorporated into what was previously known, some of which has to be overwritten, thus is the “destructive-constructive” nature of the “paradigm change” (Kuhn 1996, p.66).

“[E]ven historians of technology have tried to show that innovation adheres to a Kuhnian dynamic”, certainly, the introduction of a new games console with innovative technology would influence the designs of games, and if successful, even change how games are perceived (Fuller 2001, p.66).

“Crises” is labelled to the part of the stage of scientific research, whereby one theory, from few alternatives, has demanded the use of “tools” and whence they become useless in the fortification of that specific theory, an alternative theory is sought. This “retooling” is expensive, and is therefore named “crisis”. (Kuhn 1996, p.76). Here, a link is shown with technology, as for example, the boom of the Nintendo Wii’s motion sensing controls is hypothetically a ‘crises’ for the competing companies, as the re-defining of the way one interacts with the console has not only established a new market, but has overwritten their controls as sub-standard- no wonder it has been rumoured that Microsoft are copying Nintendo by developing a motion sensing device of their own, tantamount to the notion of the paradigm change. The developments on motion sensing from Nintendo would be classed as “sustaining technologies”, which (Christensen 2000, p.xv) describes as products which improve the performance, in favour of the market trend, of confirmed popular products.

Lazonick (2006, pp.30-31) provides a method to help cope with such ‘crises’:

“The optimizing firm takes as given technological capabilities and market prices (for inputs as well as outputs), and seeks to maximize profits on the basis of these technological and market constraints. In sharp contrast, in the attempt to generate higher quality, lower cost products than had previously been available, and thus differentiate itself from competitors in its industry, the innovating firm seeks to transform the technological and market conditions that the optimizing firm takes as ‘given’ constraints. Hence, rather than constrained optimization, the innovating firm engages in what I call ‘historical transformation’, a mode of resource allocation that requires a theoretical perspective on the processes of industrial and organizational change.”

Thus, in the regards to the successful expansion into new markets, Nintendo would be classed as the ‘innovative firm’, with motion sensing devices that have ‘transformed’ the ‘market conditions’, thus initiating the paradigm change and beginning the new cycle.

Lazonick’s (2006, pp.30-31) idea of ‘historical transformation’ and ‘organizational change’ being central to cultivating an innovative business environment that is responsible for successes like the ones seen at Nintendo’s, requires the study of organization in the innovative firm. Nelson & Winter’s, (1982) as cited in Fagerberg (2006, p.17) emphasizes that a “firms’ actions are guided by routines, which are reproduced through practice, as parts of the firms’ ‘organizational memory’…[S]ome firms may be more inclined towards innovation, while others may prefer the less demanding (but also less rewarding) imitative route.”

Kelley & Littman (2004, pp.44-45) exemplify how IDEO was more inclined towards innovation; when they were commissioned to design a new toothpaste tube, with a cleaner, less mess-making cap, they prototyped designs, and watched or “observed” the way in which people interacted and received the product. What they found was their original prototype, though looking like a good solution on paper, in practice, the testing groups found it non ergonomic. This spurred change, or innovation in the design, addressing the resulting issues, and once the design was prototyped, it excelled. (Kelley & Littman 2004, p.45) “[T]he public immediately embraced the Crest Neat Squeeze tube, buying up over $50 million worth of the product in the first year alone. Nine years and more than 1 billion units later, the package – with its on-twist cap – is still selling well with the same design.” “Astute observation is one way to shorten” the cycle of “widespread adoption” or diffusion.

Another method of organizational innovation shown “[a]t Royal Dutch/Shell…” is where employees were asked to circulate their innovative ideas by email, of which, the winners would be selected by taking into account what Shell stood to lose if the idea was ignored, and subsequent to that, “…[s]everal significant innovations at Shell began” as a result of these initiatives (Farson & Keyes 2003, pp.101-102).

However, the process is not so simple, managers usually try to nurture innovation, without taking too much risk; to truly innovate, risks must be taken and central change must be carried out at the core of business conduct, as common managerial tactics, such as ‘performance reviews’, focus on something altogether, different (Farson & Keyes 2003, p.65).

Christensen (2000, p.xii) stresses that results of studies investigated into “well-managed firms” highlight how existing business management practices falter:

“Precisely because these firms listened to their customers, invested aggressively in new technologies that would provide their customers more and better products of the sort they wanted, and because they carefully studied market trends and systematically allocated investment capital to innovations that promised the best returns, they lost their positions of leadership.”

Christensen upholds that it is important to take the “situation” into account, when applying such practices. “There are times at which it is right not to listen to customers, right to invest in developing lower-performance products that promise lower margins, and right to aggressively pursue small, rather than substantial, markets.” But how is one meant to know when to listen or not to listen to their customers?

Below, Kelley & Littman (2004, pp.27-28) provide an example of exactly how one manager took the ‘situation’ into account:

“[F]ormer 3Com CEO Bob Metcalfe” came up against a terrific force of persuasion, where “his customers and sales people practically demanded that he dedicate their R&D efforts to making a new version of its networking card for multibus-compatible computers. Metcalfe balked, and some of his salespeople quit in protest, disgusted that the company seemed to be ignoring the requests of its own customers. Instead, 3Com chose to develop an EtherLink card that worked with the new IBM PC. Today there are no multibus computers left in the world, but 3Com ships more than 20 million EtherLink cards a year.”

How this answers when to listen to the customers, is simply that organizational change into new areas, rather than the exhaustion of the previous will, if not listen to current consumer needs, will answer the needs of the consumer in the future, keeping the business current, and able to ride the winds of change.

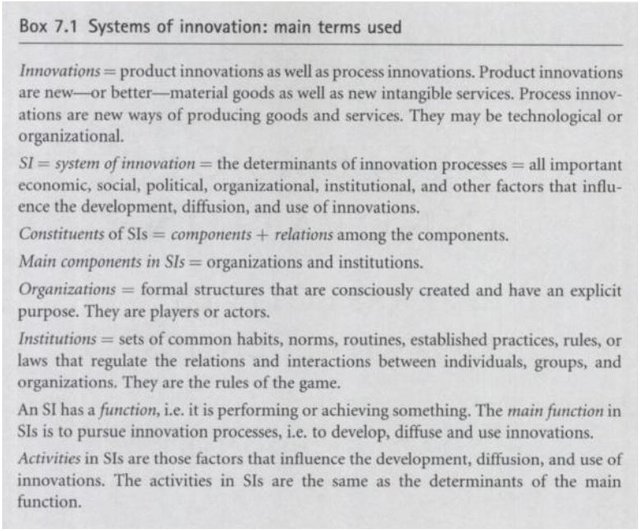

By acquiring information on the different levels of innovations within various sections of the organisation, one can identify which areas need changing. Essentially, by closely measuring and evaluating the company, the flaw can be identified. Keith Smith talks about more than one source of information that will help to measure innovation in firms. He covers; “bibliometric data”, “research and development (R&D) statistics and indicators”, “technometric [/…] synthetic indicators”, “databases on specific topics developed as research tools”, “DISKO surveys”, “patent data”, “innovation surveys”, “The SPRU Innovation Database: The Intersectoral Flow of Innovations” and the “Community Innovation Survey (CIS)” (Smith 2006, pp.148-170). Additionally, there is a systemic approach to this topic, called “the systems of innovation” or “SI approach”, explained below, by Charles Edquist:

(Box 7.1 Systems of innovation: main terms used, cited in Edquist 2006, p.182).

Edquist (2006, p.187) suggests the investigation of “relations between specific variables within SIs (which might be rejected or supported through empirical work)…to make it clearer and more consistent so it can better serve as a basis for generating hypotheses about [these] relations”, a useful method to play plumber to one’s business to find innovation leakage. Though, this method of analysis is significant, as it provides a framework and structure to measure innovation, it is underdeveloped and remains broad in its suppositions (for more information on the SI Approach, see Edquist (2006, pp.179-208).

The question of when to use these methods of organisational change and identification of said areas has not been outlined. If a business is profitable, does it need to adapt to potential future markets, indeed can a company be successful without innovation? Schumpeter (1934, p.xix) argues that innovation provides the blueprint for new “economic development”, such as the application of new business strategies, processes, “method[s] of production” etc.

Conversely, Pavitt (2006, p.87) maintains that “[e]conomists tend to concentrate on the economic incentives for, and the effects of, innovation (largely ignoring what happens in between).” Reverberated by O’Sullivan (2006, p.240), who believes that “contemporary economists of innovation have largely neglected the relationship between finance and innovation.” O’Sullivan (2006, p.261) suggests to source information on the financial demand and supply of businesses, to reveal the relations between finance and innovation, “[h]owever, the current, rather dire, state of empirical research on patterns of financial demand and supply mean that this option is not available.”

What is available however, is the study of growth and innovation across global economies. Schumpeter, (193-) as cited in Fagerberg (2006, p.18), shows how the Schumpeterian model “to explain long run economic change”, was “applied” to examine the “cross-national differences in growth performance”. The model was “(1) that technological competition is the major form of competition under capitalism (and firms not responding to these demands fail) and (2) that innovations, e.g. ‘new combinations’ of existing knowledge and resources, open up possibilities for new business opportunities and future innovations, … [thus] set[ting] the stage for continuing change.” Thus, even companies that experience profitability are unstable till they begin organizational change to adapt to future markets, consequently; this should occur before the cycles of innovation restart otherwise the business may fail. This argument insists that innovation is central to wealth creation.

Posner, (1961) as cited in Fagerberg (2006, pp.18-19) furthered this theory with an “influential contribution” to this model explaining “the difference in economic growth between two countries, at different levels of economic and technological development, as resulting from two sources: innovation, which enhanced the difference, and imitation, which tended to reduce it.” Fagerberg (1987), Fagerberg & Verspagen, (2002) as cited in Fagerberg (2006, p.19) draw the conclusion “that, while imitation has become more demanding over time (and hence more difficult and/or costly to undertake), innovation has gradually become a more powerful factor in explaining differences across countries in economic growth.”

Although, even this assumption that innovation, rather than imitation, results in economic growth has met scrutiny. Verspagen (2006, p.488) alleges that “[a]lthough the argument that technological and organisational innovation are responsible for…gradually accelerating growth [in the world’s economy]…, in fact economic theories explaining any such relationship are far from straightforward.” Yet, this does not disprove that innovation is highly regarded in the explanation of economic growth, which corroborates my hypothetical argument that ‘game ideas with more innovation sell better, than ones with less’.

What is true of innovation, even if it is a catalyst in economic growth, is its unpredictability. Innovation is an expensive process, needing resources to keep the process going and undertaking innovation may not always yield profit, because of its inherently risky nature (O’Sullivan 2006, p.240).

Innovation it’s practice, presents a few problems. Firstly, with something that has not been done before, there is no example to follow, or no knowledge to learn, though theories and experimentation help construct confidence, there is no hard knowledge to build on. Secondly, it requires going against the flow of contemporary knowledge, sometimes even going against long help beliefs. Thirdly, there are Intellectual Property Rights and patents etc. hurdles to overcome (Schumpeter 1934, p.xxi). Pavitt (2006, p.88) agrees, but adds the process whereby one seeks to forecast sales figures for a particular product by “…(trial and error) or improved understanding (theory). Some (but not all) of this learning is firm-specific. The processes of competition in capitalist markets thus involve purposive experimentation through competition among alternative products, systems, processes, and services and the technical and organizational processes that deliver them.” Again, this limits the creation of the product to suit market needs; what the consumer wants. However, this method, when researching a new product’s reception to the market, provides reputable insight, because “…what needs to be learned about transforming technologies and accessing markets can only become known through the process itself” (Lazonick 2006, p.30).

The error part of trial and error is important. Mistake making, to innovators and inventors are signs of progress, in the search for innovation. By letting go of old successes, creating something new is easier, but more likely to fail; the more mistakes you make, the closer to happening on a success becomes (Farson & Keyes 2003, p.33). Unfortunately, the majority of managers fail to allow innovations to flourish, because they are trained to follow the existing codes of practice (Berkun 2007, p.96), even though “[s]hortcomings and failures that occur at various stages may lead to a reconsideration of earlier steps, and this may eventually lead to totally new innovations” Kline & Rosenberg, (1986) as cited in Fagerberg (2006, pp.8-9).

Farson & Keyes (2003, p.81) demonstrate that innovative firms can benefit, even from the mistakes inherent in the process of invention; Post-It Notes were a spin-off from a scientist’s failed attempt to create a powerful adhesive. The reusability of the resulting weak glue was recognised by a man at 3M who saw its potential as, when applied to yellow paper squares, became a useful re-stick-able reminder.

Though the practice of mistake making or, risk friendliness may sound discouraging, Kelley & Littman (2004, p.13) have confidence that “creativity” sells and that consumers latch onto anything new and exciting. The companies that are willing to expand by creativity, taking on new approaches to situations, preparing for some failures by cultivating an innovative, risk friendly atmosphere, are more likely to succeed. This environment “helped IDEO grow from a two-person office into the leading product design firm in the world” (Kelley & Littman 2004, p.14). IDEO (2008a) is a “global design consultancy”, which “create[s] impact through design.” IDEO (2008b) has won “346 awards won since 1991” and “ranks #5 on Fast Company's list of the World's 50 Most Innovative Companies” IDEO (2008c).

This research has shown that firms who keep up with ever changing consumer needs, are the ones who actually create the needs, by making these new markets attractive to the consumer by their creative ability; another variable in the innovation process.

Hi, I'm wondering if anyone knows how to take a word doc, with images and formatting, then put it into a post, with minimal hassle, while keeping formatting, images, headings, bold, spaces etc. please, it would really help!

Also, let me know if you want more posts like this, as I have a lot of game related topics!