Of Parades and Riots: a brief history of the commodification of queer liberation.

a/n: this is an essay i wrote when i first started university. i never did anything with it so i thought i'd give it a home and leave it here.

At nearly fifty years since the Stonewall Riots, same sex marriage has been legalized across the United States, however, the movement that set the fight for equal rights in motion is long gone. In this essay I will discuss the transformation from Gay Liberation into Gay Rights, respectability politics, and the commodification of the queer movement by the mainstream.

From its beginnings, transgender women, and particularly transgender women of color have played a fundamental role in the advancement and development of the queer community. Through the second half of the XX century the faces of the queer struggle and the subsequent riots and demonstrations that took place were the impoverished and marginalized. The Gay Liberation movement was tightly bound to other activist groups that surfaced during the late 60’s, such as the Civil Rights, Women’s Liberation and Anti-war movements. Sylvia Rivera, one of the most important queer activists of the time, was also known to be involved with the Black Panthers and the Puerto-Rican movement The Young Lords. She spoke about the influence of the queer community in other counterculture groups during an interview in 1998;

“All of us were working for so many movements at that time. Everyone was involved with the women’s movement, the peace movement, the civil-rights movement. We were all radicals. I believe that’s what brought it around. You get tired of being just pushed around.”

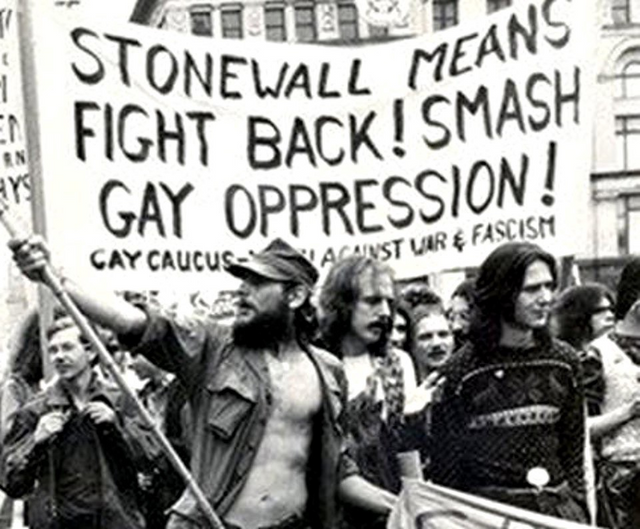

Amidst the rise of these radical groups, solidarity became key to their survival, finding support within each other’s communities and being able to identify with one another’s fight for freedom and equality. The Gay Liberation Movement borrowed many concepts and statements from other radical groups, such as the chants of “Gay Power” during the Stonewall Riots, taken from the Civil Rights Movement’s “Black Power”. It was commonplace for queer protestors to sing “We Shall Overcome”, a well known Civil Rights Anthem. These movements formed an alliance and stood together against the repression of police and the government. Folk singer Dave Van Ronk, who was present during the Stonewall Rots although he was not gay himself, is quoted in David Carter’s Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution as saying: "As far as I was concerned, anybody who'd stand against the cops was all right with me, and that's why I stayed in... Every time you turned around the cops were pulling some outrage or another."

It was people like Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson who sparked the resistance against the unjust violence and discrimination the gay community had been subject to up to that point.

Having run away from home at age 10, Sylvia Rivera was taken in by drag queens who she stayed with until age 18, and so the focus of her activism was directed at those with similar experiences to hers, dealing with homelessness, poverty and addiction, and relying on sex work for their income. Similarly, her close friend Marsha P. Johnson became an icon of queer revolution and one of the most well known drag queen activists in New York City at the time.

Together they founded STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries), an organization aimed at taking in homeless LGBTQ youth. They offered them housing and kept them fed, hustling the streets in order to keep the kids from having to do the same.

“STAR was for the street gay people, the street homeless people and anybody that needed help at that time. Marsha and I had always sneaked people into our hotel rooms. Marsha and I decided to get a building. We were trying to get away from the Mafia's control at the bars.”

Both of them were present the night of the Stonewall Riots, along with other prominent figures of the LGBTQ movement such as Miss Major, an activist who advocates to this day for the rights of transgender people, especially women of color.

The police raided the Stonewall Inn, known for being frequented by poor, usually homeless gay and transgender people, on June 28 in 1969. The reasons behind this raid are not clear, and many rumors about it spread during the following days. There is some evidence that the police and the mafia were blackmailing the wealthier clients of the bar, particularly those who worked in the financial district, which lead to the theory that after this source of income was no longer viable they decided to shut down the bar for good.

During these raids, police officers would “verify” the sex of any person dressed in women’s clothes to arrest those considered to be men dressed as women. Male officers often assaulted the lesbian customers, feeling them up as they frisked them. As they waited for patrols to arrive, a crowd started forming outside the bar. Those in custody began to resist arrest and refuse to follow police’s orders, and violence finally broke out. Sylvia Rivera recalls the police being scared of the Stonewall customers, as they had not expected any resistance.

"People started throwing pennies, nickels, and quarters at the cops. And then the bottles started. And then we finally had the morals squad barricaded in the Stonewall building, because they were actually afraid of us at that time. They didn't know we were going to react that way."

"We were not taking any more of this shit. We had done so much for other movements. It was time."

Ten police officers barricaded themselves in the inn as bricks, rocks and bottles were thrown at the building. A parkimeter was used to keep the door of the bar shut. Marsha P. Johnson is said to have climbed a lamp post to drop a bag onto a police car, breaking the windshield in the process.

"Finally the Tactical Police Force showed up after 45 minutes. A lot of people forget that for 45 minutes we had them trapped in there."

The events of that night were unprecedented; it was the first time the gay community, and particularly this marginalized section of it, responded to violence with violence, and the first time the police had been forced to step back. It was a humiliation to the police force, especially coming from the gay community, which fueled the hostility between the two bands. The main gay organizations of the time, such as the Mattachine Society, that advocated almost exclusively for the rights of gay men, attempted to get accepted and ingrained into society by presenting themselves as equal to heterosexuals in behavior and practices, as “normal” citizens, rejecting performances of femininity and radical ideology. Their demonstrations were usually pacific, a prime example being their annual picketing at Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. During these demonstrations, men wore suits and women wore skirts, marching quietly, and so the night of the Stonewall Riots marked a turning point in gay history.

That first display of defensive violence detonated a series of riots that extended throughout the following week, which were joined by other groups who often had confrontations with police.

This resulted in an array of meetings and gay organizations, including the Gay Liberation Front, which was the first organization to include ‘Gay’ on its name and the Gay Activists Alliance, as well as the publishing of a local gay newspaper, mainly due to other paper’s refusal to print the word ‘gay’.

A year later to commemorate the anniversary of the Stonewall riots the first Gay Pride March, then called Christopher Street Liberation day, was celebrated in New York City.

The concept of Gay Pride was, at its roots, an act of rebellion against a hierarchy that retaliated LGBTQ people’s existence with hatred and violence, as well as a reaffirmation of identity outside of the norm of what was deemed acceptable in a heteronormative society. Gay Pride was unapologetic and defiant.

Throughout the coming decades, however, commemorations of the Christopher Street Liberation Day started to lose its revolutionary character to appease the more conservative members of the Gay Community, leaving behind the radicalism that served as a catalyst for the queer struggle to come to light the night of Stonewall. This is when words like “Liberation” and “Freedom” began to be dropped from the names of organizations and the parades themselves, being replaced by simply “Gay Pride”. “The movement was no longer about the freedom to be different, but the chance to be the same.”

During this process, the original ideas of this liberation movement were pushed to the back of the parade along with those who held them. The contributions of poor trans women of color were, and still often are, erased and their legacy became co-opted by the rest of the gay community. This was also encouraged by the rise of trans exclusionary radical lesbian feminists during the early 70’s, notably activist Jean O’Leary, who considered drag and transgenderism as a mockery of women and their struggle.

In spite of this, the Stonewall Riots had a major impact of the way homosexuality and gender non-conformity were viewed by the rest of the population in that era. Many people who lived through this time of change recall that homosexuality was starting to become accepted, they were beginning to gain visibility and the shame that used to rule over the LGBTQ community prior to the Riots was replaced for a general feeling of empowerment and hope. Sodomy laws and anti-gay laws started being repealed in many states. Harvey Milk, the first openly gay official in California, was elected in the late 70’s, and when he was murdered, the Gay Community came out to the streets again during the White Night Riots in what is cited as the second most violent gay demonstration after Stonewall. The movement was growing and demanding respect. People were finally standing up for themselves.

Then the first cases of the AIDS epidemic started to show up. In the early 80’s it was estimated that up to two cases were being reported daily, however numbers escalated quickly as the so-called “gay plague” spread throughout the country. People were dying by thousands, and yet the government remained unconcerned about the issue, ignoring the calls for action from those affected. Ronald Reagan’s press secretary, Larry Speakes was first asked about it during an interview in October, 1982, and, in between laughs, claimed not he nor the president knew anything about the disease, saying “there has been no personal experience here.” When pressed on the issue, he joked and evaded the questions. He was asked about it again in June, ‘83, and again in ‘84, both times with the same results.

Abandoned by the system and the authorities, the LGBTQ community had to rely on each other to survive the crisis. It was organizations like ACT UP (AIDS Coaliton to Unleash Power), which included prominent queer figures such as Marsha P. Johnson, David Wojnarowicz and Keith Haring, that took the job of spreading awareness and helping those who were infected. AIDS hospice centers were almost exclusively run by queer people, many of whom were ill themselves. The deaths were happening at such a scale that people in the gay community could no longer keep track of which of their friends acquaintances were still alive. The fight for same-sex marriage gained traction during this era; those who managed to get taken in by the hospitals often died alone, as their partners were denied visiting rights. People would do ‘die-ins’ where they would lie down in public spaces, such as the outside of hospitals that refused to assist them, and die there, quite literally using their last breath to protest the government’s neglect.

In the wake of this crisis, the Names Project AIDS Memorial Quilt was born out of an urge to preserve and celebrate the memory of those who were taken by the epidemic. When someone died, their loved ones would sew up a panel for the quilt, roughly the size of a grave. These pieces traveled across the states, and were often displayed in public spaces, while people took turns reading out the names those panels belonged to. The Quilt weighs over 54 tons, bearing the names of around 100,000 people, and only accounts for a small fraction of the population who died due to AIDS related causes.

The AIDS epidemic managed to nearly wipe out an entire generation of gay people, and along with them, all the progress that had been accomplished since Stonewall. It created a new stigma and rebuilt old ones. It destroyed relationships and divided communities, and furthered the marginalization LGBTQ people had been experiencing for decades.

The AIDS crisis could have been contained, but medicine was monopolized, the production of it by generic brands banned, and made unaffordable to the poor, the sector most affected by it. The Government did not only ignore this, but also profited from it; the people who died left behind their apartments, usually in government owned buildings, which would get more and more expensive. Often, the heat would be off in these buildings during the winter to accelerate the deaths of the tenants. This resulted in the gentrification of areas that originally fostered gay communities, including Greenwich Village, home of the Stonewall Riots.

Another common practice was the purchase of the insurance of infected people; AIDS victims would often legally appoint their insurance to people who in turn paid their monthly medical bills. Many people became wealthy through this acquisition, and the quicker the death, the more profit they were able to obtain out of the deal.

A lot of this history tends to be forgotten by the modern LGBTQ movement, the brutality erased and the grief buried though this all took place less than fifty years ago, and though LGBTQ people still experience high rates of violence and abuse. The anger has been replaced by a form of quiet discomfort, and Pride has gone from a celebration of queer revolution to merely a celebration.

Chants of “Gay Power” have changed into “Love is Love”, a phrase that negates the political implications of the gay struggle and simplifies them into a matter of sentimentality rather than a violation of human rights. The same rhetoric has allowed the fight for same sex marriage to become a safe cause to support, and an endgame rather than a milestone. Marriage has turned into the be-all, end-all of equality, and so it has been used to declaw and depoliticize its own movement.

Major corporations have not fallen behind on exploiting the LGBTQ community either, especially during the aftermath of the legalization of same sex marriage. Many companies have come out in “support” of marriage equality, although their support seems to be limited only to adding rainbows to the packaging of their products to appeal to liberal demographics. Alcohol companies claim to endorse the queer community, while at the same time taking advantage of queer people’s high rates of alcoholism and addiction. Queerness has been commodified by large corporations that sponsor Pride Parades and related events, successfully using these demonstrations to promote their brands.

This is how the mainstream media, the government, corporations, have learned to successfully quell any demand of change coming from the queer community; by positioning themselves as allies and turning the movement against each other, getting the most visible members of the community to side with them and turn their backs on those who follow the queer movement’s tradition of challenging the established norms, of radical thinking and radical action, of fighting back against repression. Those who are most vulnerable, who most often are subject to violence and discrimination, have been left behind and forgotten, as has the legacy of Stonewall. And the movement has facilitated that, often centering around the privileged and most accepted. Laverne Cox, a transgender woman of color who has gained visibility in mainstream media since her role in the Netflix show Orange is The New Black, has discussed this, citing Sylvia Rivera:

"She warned us against becoming a movement only for white middle class people, this was 41 years ago, and today, so much of the ways in which LGBT equality has played out has been about white middle class people. "

There are still those who refuse to conform, who refuse to forget their history, the anger and grief and desperation that built this community as it exists today. However, most of the LGBTQ community nowadays seems content to adapt, to take just what they can get, to celebrate rather than protest.

We can only hope that the fire that first sparked the desire for change in Stonewall can one day be reignited.

Sources

Rivera, Sylvia. "I'm Glad I Was In The Stonewall Riot." Interview. 1 Jan. 1998.

Carter, David. Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution. New York: St. Martin's, 2004. 156. Print.

Cohen, Jon. Shots in the Dark: The Wayward Search for an AIDS Vaccine. New York: Norton, 2001. Print.

I am new here and have a Spiritual Lesbian Blog. Nice to meet you. Linda E Cole NZ