29. It was stigmatic to be a member of that unit

Precursor to the Mỹ Lai Massacre: 1968 Phong Nhị, Phong Nhất_29: Interview with Choi Young-un, 1st Platoon Leader

Choi Young-un in the interview of summer of 2013. Photograph by Humank

Lieutenant Choi Young-un became a broadcasting producer.

March 31, 1971 was his day of discharge, whereby his five-year service as a marine officer, including the time he was dispatched to Vietnam, would finally come to an end. On April 1, the very next day, he went to work at the Munhwa Broadcasting Corporation (MBC) whose building was in Jeong-dong, central Seoul, and where a career in broadcasting awaited him. At first, he was in the general affairs department, but soon joined the sports department. He was beginning a brand new chapter of his life as a sports producer who plans various sports broadcasting programs.

By the time I met Choi Young-un in April 2000, he had already retired from MBC. He ended his 27-year career, his final position being sports director, in October of 1998. For a year after retiring from MBC, he served as secretary general of the Korea Baseball Organization (KBO), overseeing administration in the professional baseball community. When we met, he had been completely retired.

That day, he provided me with a very instrumental testimony, a story he had never uttered while working in broadcasting or sports for 28 years: In February 1968, South Korean marines caused a mishap in the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất areas, where firing was restricted, and the company officers were later investigated by the Korean Central Intelligence Agency. He was the commander of the first platoon which was the first to enter the villages. All I had said over the phone was, "You fought in Vietnam, correct?" yet he said he felt jolted, thinking, "Something that has been concealed for more than 30 years is finally making its way into the light." Thanks to his testimony, my coverage of other platoon commanders was able to gain momentum. Lee Sang-woo and Kim Ki-dong, former 2nd and 3rd platoon commanders whom I got to interview thereafter, also admitted that they were investigated by the CIA, a fact that was reported as a cover story in the Hankyoreh 21, a weekly current events magazine. Later, Sung Baek-woo, a former head of the investigation team of the 2nd Brigade of the Marine Corps, made a conscious declaration after hearing this article being introduced on a radio station.

Thirteen more years had passed since then, and on March 23, 2013, I met Choi Young-un again. After deciding to publish a book on the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất incident, I tried again to meet with all the former commanders of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd platoons, but it wasn’t as easy as I had thought. Lee Sang-woo, who served as the 2nd platoon commander, could not be reached, and though I was able to reach Kim Ki-dong, who served as the 3rd platoon commander, by phone, he refused to meet me. Choi Young-un, with whom I met on a Saturday afternoon at a cafe in Ilsan, Goyang, had become an elderly man in his early 70s, but his resolve remained intact from 13 years ago, when he was still in his late 50s. His memory also remained clear. We made small talk, sharing our past life stories before we dove into a full-fledged interview. I asked him to meet with me frequently going forward and tell me stories about the old days. He didn't refuse.

Choi Young-un (left) enjoying playing in the water with his subordinate at Da Nang's beach in 1968. Photograph provided by Choi Young-un.

Since then, I met Choi Young-un more than 10 times. I was planning on asking for details of the day of the incident as well as the time he was being investigated by the Central Intelligence Agency, but the story extended beyond my expectation. His life was an exciting drama series. The story of the Marine Corps' attack on the Gimhae Air Force School that Choi incited before leaving for Vietnam (August 8) and the story of exchanging military currency certificates were my biggest gains. The commotion surrounding the U.S. military's PX in Da Nang also aroused my curiosity. There were other smaller yet interesting episodes from before and after his dispatch to Vietnam. I was also quite impressed by his stories from his days in elementary school, not to mention the fact that he had become a sports producer after being discharged from military service.

If one looks into the Vietnam War with Choi as the main character, one could find a mixture of the two novels, The White War, and The Shadows of Weapons. Ahn Jung-hyo's The White War approaches the violence and wounds of war through the lens of humanism, while Hwang Seok-young's The Shadows of Weapons reveals the political and economic side of war: the gambling of the powerful. Having lived in military prison for 45 days for leading the Marine Corps in a raid on the Gimhae Air Force School, Choi was sent to Vietnam later than his other marine colleagues. Consequently, his experience in Vietnam was far more varied and colorful. After five months of fighting in the forefront as a platoon leader, he took over as deputy chief of staff and the personnel administrator of the battalion because his rank was higher than other marines who joined the same year. Choi Young-un witnessed both a white war from the front line of gunfire and the shadow of weapons from the rear, a little way from the front, as Deputy Chief of Staff or Personnel Administrator.

What made me most curious was the mystery behind the incident of Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất. Choi Young-un, the first platoon commander who entered the villages, drove the residents out and then exited west. The moment he found a dead snake in front of a small pool of water, he heard guns being fired in succession. It was likely true that the 1st platoon was not responsible in any of this, given the statements of several Marine officers, including the 2nd platoon commander. Then who had fired the gunshots? Who shot and killed the residents and mutilated them with knives? During an interview in April 2000, Choi had denied knowing anything. Whenever I met him, however, I would ask him again until one day he finally opened his mouth, admitting that word has it that it began among the third platoon. But Choi didn’t know why either. He just said he thought they were crazy since there were only unarmed women and children, and that unless the platoon members were suffering from some kind of mental illness, they had absolutely no reason to have done so.

Choi Young-un's view of the Vietnam War was neither radical or forward-looking. For him, the Vietnam War is not a war of insanity. Rather, it was an opportunity to enhance the national prestige of the Republic of Korea. He never denied the positive significance of the war, to which since the dictatorship of Park Chung-hee there was only a single motive. For Choi Young-un, the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất incident was just an accident. He and I had different ideas, but we didn't argue about this. As the number of encounters grew, I concluded that he was a "cool-headed conservative."

By conservative, I mean that he supports South Korea's anti-communism and sincerely respects Park Chung-hee. He had never voted for a non-conservative party in the elections so far. Nevertheless, I call him “cool-headed" because he still understood the nature of war. Why does the U.S. go to war? For bread and butter. He knew how vicious the U.S. military was in the Vietnam War for the sake of bread and butter. His view of the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất incident is likewise very level-headed for a conservative. He admits that the Korean troops were acting out of insanity that day.

I also got to know Choi apart from his political views. He was born in December of 1942 in Yangjeong-dong, Jin-gu, Busan. His father was a railroad official. Choi Young-un was the first of three sons and one daughter. Because of his father’s job, which required relocating back and forth between Seoul and Busan, the Choi siblings also had to move back and forth frequently. In 1950, when Choi was in the 2nd grade at Yongsan Elementary School in Seoul, he transferred to Busan Jin Elementary School, and the Korean War broke out a week later. After the cease-fire in 1953, he returned to Seoul where he attended Sam-gwang Elementary School in Yongsan and continued on to Yongsan Middle School. He later transferred to Busan Middle School and then graduated from Busan High School.

"It must have been 1959. I marched to Masan in a demonstration when I was a sophomore at Busan High School. At that time, Park Chung-hee was the commander of Busan's military base. I don't remember much, but I recall walking with a slogan about democratization. It was a long distance to Masan, so everybody was exhausted. They couldn’t possibly walk back to Busan from Masan. Parents were worried and upset. They sent buses for us to return home in."

He entered the department of physics at Hanyang University in 1961. He eventually graduated with a degree in mathematics instead, but was not interested in academics. When he was a sophomore, he tried out for the school football team.

"In college, I only played football. I became captain of the team my junior year, and we won seven collegiate games in Seoul. At that time, Kim Yeon-joon, the chancellor of Hanyang University asked the football team to help stop students from demonstrating for democracy. Park Kyung-hwan, my late professor and advisor frequently blocked such requests to the team. I was always working out for football, so even when I was taking the physical exam for the Marine Corps, it was almost a joke."

In December 2014, the last time I interviewed Choi Young-un and took a photograph with him. Photograph by Humank

After graduating from college, he volunteered at the Marine Academy, which selects a marine officer. He decided he wanted to become a Marine officer when he saw his upperclassman friend from Hanyang University wearing a Marine officer's uniform and thought he looked so cool. Choi asked him, “How can I do what you’re doing?” He was just about to get his army conscript order. At the time, the service period was three years for the Army and three years and three months for a Marine officer. The latter was longer by a measly three months. But when Choi enlisted, the service period was extended to five years due to a shortage of officers during the Vietnam War.

He believes that the Marines are strong. His pride for having fought in such a strong organization is unbreakable. He stated that the most fearless age for human beings is when they are in high school and college. Human beings are born with energy in their hands and feet, which is why children don’t get frostbitten even if they play outside on a cold winter day. Their hands and feet only get red. But in high school and college, this same energy transfers over to one’s heart. That's why the youth are so fearless, and the Marines so strong. One could volunteer from the age of 18, and volunteers were mostly young kids who have experienced hardships, delivering Chinese food and polishing shoes to make money. Children whose parents were divorced or whose father's business has gone bankrupt, so they learned how to survive in society from a very young age. They are extremely shrewd and reckless, not to mention, fearless. According to Choi, these guys can easily withstand war.

Regardless, Marines were human beings too. With the Vietnam War approaching, Lieutenant Choi Young-un could not exactly shake off the shadow of fear that was looming over him. He remembered a certain article from the magazine, "Arirang" that he saw in Korea before his deployment.

"Arirang was a comprehensive monthly magazine. It was a thick book of about 300 pages, and there was an article written by a Marine lieutenant who was two years ahead of me. It was a shocking article, titled "You retards." It’s about a Marine officer who was injured in Vietnam and was admitted to the Dapsimni Naval Hospital. Even at restaurants, he gets the stink eye, and the woman he was dating comes to the hospital once, never to return, and gets engaged to another man a month later. He mentions the name of a bar hostess, whom despite her marigold teeth, he liked best. Reading the article made me so sad that I vowed that I would die if I have to in Vietnam but not get injured. I cut out the article and hung it on the wall of the platoon room to read every day."

His brother, Choi Jeong-un, who was three years younger, was also a former Vietnam veteran. He changed his path after suffering from long-term effects of exposure to defoliants 10 years ago. He had graduated from Yonsei University with a major in economics and worked at the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, garnering high expectations from his family.

"We had to wear long sleeves and bulletproof vests in the jungle. Even when we were sweating as if it were raining, we still had to arm ourselves to survive. In the rear, you roamed about topless, wearing shorts, which increases your exposure to defoliants. My brother was in the human resources department of the Capital Mechanized Infantry Division, also known as Tiger Division. He was in Vietnam at about the same time as I was."

His six-year-younger brother, Choi Soo-un was a marine soldier. Therefore, two of the three brothers, Young-un, Jeong-un and Soo-un, had ties to the Marine Corps or the Vietnam War in some way or another. The youngest, Soo-un, went as a recruit when Young-un was at the Landing Post Command in Pohang. Soo-un actually wanted to go to Vietnam, but his older brother, Young-un, made a special request to the commander, asking for an indirect way for his younger brother to evade being dispatched to Vietnam. He deemed it was bad enough that even one of the brothers had to go to war, and that there was no need for two of them to go. He therefore secretly tried to get his brother into the department of chemistry, since Soo-un had a background in chemistry, and there was no demand for chemists in the Second Brigade of the marines in Vietnam. Soo-un therefore ended up joining the Army instead, which prevented him from going to Vietnam.

What was war to Choi? What significance was there for him? “Our country sent troops to Iraq or Afghanistan, but it was for security and restoration. But in Vietnam, we were completely immersed in battle. Whatever orders the state gave, we had to follow, which led to a great number of victims. I don't have anything to say about those who lost their lives; all I can say is that I am fortunate to be alive, and I'm happy to have contributed to my country. Their destiny could have been mine, and I could have been the one lying in the National Cemetery. But here I am, having a drink with a journalist like you. I’m still suffering from the defoliants, though, which means the country isn’t doing such a good job of looking after us."

I showed him the photographs I took in Vietnam. Choi looked pensively at the photographs of the monument, of the memorial services of the bereaved families of Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất, and of Nguyễn Thị Thanh, a young woman whose breasts were mutilated with a knife by the marines.

"It's so tragic. If I were to meet these people, I wouldn’t have anything to say. It's a sad story. I wasn't entirely human; I was partially a robot, taking orders. If they say, shoot, I would shoot. Even if I get down on my knees and beg for their forgiveness, it won’t change a thing for them. Our paths crossed in the worst way possible, wouldn’t you say? There is no good response to any of this."

The 1st platoon, which he commanded, was spared from the direct responsibility of the killing. But he nonetheless felt heavyhearted.

"It was stigmatic to be a member of that unit. And they shouldn’t group us into one like that."

In the early 2000s, Choi went down to Seogwipo in Jeju Island and worked for five years as the chairman of the operation committee for a resort called, "Jeju Baseball People's Village." It was his last social activity. Having won many championship titles as the captain of his college football team, Choi made a name for himself as a sports producer at the Munhwa Broadcasting Corporation. When professional baseball was launched in Korea in 1982, he led the establishment of a broadcasting system for television as deputy chief of the sports production department, and in the 1990s, he successfully organized big events such as the invitational game of Cameroon's national soccer team (1994). Now he visits the local library on occasion and spends time with his old friends. Choi, who is the same age as Kim Jong-il, former chairman of the National Defense Committee of North Korea, and Lee Kun-hee, Samsung Electronics Chairman, walks well with his healthy pair of legs, unlike the two who either passed away or is in his sickbed.

At 1 p.m. on November 2, 2014, we had our last interview at a restaurant in Ilsan, Goyang City. I asked him all the questions I didn’t get to asking previously. He answered them in detail. At about 4 p.m. we took to the streets. Autumn leaves were flying in the wind. We went into a beer house and had two pints of draft beer each. Some trivial small talk ensued, with his explaining for a long time his secret to maintaining his health.

I thanked him before I left at about seven o'clock. As a veteran who believes that the Vietnam War contributed greatly to the development of Korea, the subject of Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất may have made him uncomfortable. Nevertheless, he answered my many questions to the best of his abilities. There was even a time he threatened to sever ties with me, angrily saying, "Don't write about me and the Marine Corps." What seemed like a crisis in our relationship actually served as an opportunity to better understand each other. I trusted and respected him, but not to the extent of blindly accepting everything he said as facts. He may have experienced all sorts of things because of the war, yet still, his recollection of the war was only but a fragment of the entire picture. With that in mind, I decided to take what I can take from his stories and disregard whatever seemed irrelevant. Just before parting, he stuck out his hand for a handshake and said, “Well, it seems my job is done; you’ve gotten what you wanted out of me. No need to see each other anymore, ey?” He seemed aloof in making this remark, and I did not say anything to him in response.

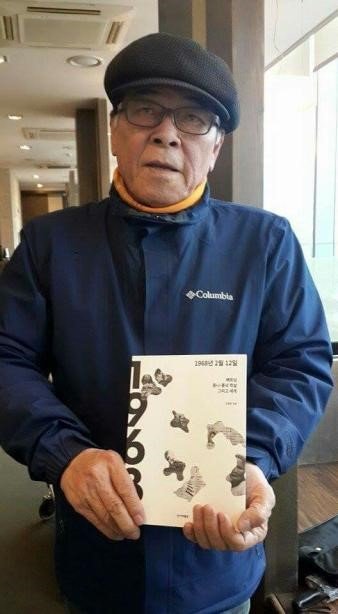

I met Choi Young-un after the publication of February 12, 1968, which contains records of his time in Vietnam. Choi Young-un holding this book . Photograph by Humank

Since then, the stories were interwoven into a book titled February 12,1968, published in February of 2015. Even thereafter, I met with Choi Young-un at least once a year. I would be the first to call, suggesting we grab a meal together. With his meals, he would always order the soju with the red bottle cap, which had high alcohol content, and would easily empty two bottles on his own.

The actual last time that I met him was for lunch on Saturday, December 23, 2017, with 2018 just around the corner. That day, even as he was telling me that he was regularly going to the Veterans' Hospital for checkups, he ordered his usual soju with the red cap. He also said that he had been contacted by several reporters and television producers who wanted to hear his testimony about the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất case. I was the one who had given out his number. He said in an irritated tone that he just hangs up on them without bothering to hear what they have to say. Perhaps because of his deteriorating health, he said he’s exhausted now and does not want to talk about the Vietnam War anymore.

That day, he avoided the topic altogether and talked about other things. He excitedly shared that his former colleague, who was the youngest at the time when Choi was the deputy director of MBC Sports, recently filled Choi’s former spot as director. He also criticized the Moon Jae-in administration for spending too much money on the Sewol Ferry incident. After finishing our meal at a restaurant located in Hwajeong, Goyang City, Gyeonggi Province, I drove him downtown. Before we parted, I handed him a small gift. His voice cracked, as he said, “Thank you.” I had no idea that that would be our last time. Three months later I received a text message with him as the sender. It was an automated obituary announcing that “the late Choi Young-un passed away on March 22nd."

- Written by humank (Journalist; Seoul, Korea)

- Translated and revised as necessary by April Kim (Tokyo, Japan)

The numbers in parentheses indicate the respective ages of the people at the time in 1968.