28. The Dark Cloud of the Symington Hearing

Precursor to the Mỹ Lai Massacre: 1968 Phong Nhị, Phong Nhất_28: The Dark Cloud of the Symington Hearing

Click to read in Korean(태풍의 냄새, 박정희는 미리 맡았나)

Minister: We called you here today to discuss some of the concerns between the two countries, but first, please tell us what the current situation is with regard to the Symington subcommittee.

Deputy Ambassador: The Symington subcommittee is expected to commence on February 23 (actually on February 24) for about a week, and it will discuss the U.S. defense commitment to Korea, and the 'Brown' memorandum.

Minister: The Symington subcommittee says it will hold a hearing as a secret meeting, but there are also rumors about the Brown memorandum, which should not necessarily be made public.

Deputy Ambassador: I agree, but with the National Assembly, there are cases where individual discussions may be leaked. I know the administration will try to prevent such instances, but even for the sake of the Korean government, matters should most definitely not be openly discussed in the Korean newspapers.

Minister: Of course, the Korean government is trying to keep these issues at bay, but you should also keep in mind that it is difficult to keep the press quiet (…)

Minister: According to the contact we received from the Department of Defense, the military aid during the 70s amounts to $140.5 million; is this fact well-grounded? If so, it would be a serious problem, given that even if we had 160 million dollars, we would barely be able to maintain the status quo. If there is going to be a budget cut of more than $20 million, we couldn’t possibly replace old equipment and handle rising operating costs.

Deputy Ambassador: As far as I know, Ambassador Porter met with the Prime Minister and talked about the issue before leaving for the United States for the Symington subcommittee. I also know that key figures in the Korean government are aware of all this (…)

Minister: Please make sure you report to Washington the Korean government's position that the U.S. should not reduce military aid to Korea at any cost, as well as our keen interest in this matter.[1]

On Friday, February 20, 1970, at 11:30 a.m., Minister of Foreign Affairs, Choi Kyu-ha spoke with L. Wade Lathram, Deputy U.S. Ambassador to South Korea. Something was urgent. It was the Symington hearing. The Symington hearing was an investigative subcommittee on security treaties and foreign defense commitments chaired by the U.S. Senator Stuart Symington. The hearing was four days away. South Korea was last to speak, from February 24-26. The Philippines (Sept. 30, 1969), Laos (Oct. 20-22, 1969), Thailand (Nov. 10-14, 1969), Free China (Taiwan, Nov. 24-26, 1969), and Japan and Okinawa (January 26-29, 1970) had all gone before. They were all Asian allies who had sent troops or provided bases to Vietnam with money from the U.S. government. The hearings were supposed to examine whether the money was spent properly. From the administration side, Winthrop G.Brown, assistant secretary of state for the Asia Pacific region, John H. Micheles, commander of U.S. Forces Korea, and William J. Porter, U.S. Ambassador to South Korea, were scheduled to be at the testimonial table.

A front-page report on the Kyunghyang Shinmun, dated February 24, 1970, announcing the Symington hearing.

With the hearing soon approaching, the South Korean government felt it needed to at least speak to deputy ambassador, Lathram since Porter himself were unavailable as he had returned to the U.S. for the hearings. Minister Choi Kyu-ha conveyed to him the "concerns of South Korea" surrounding the hearing. The point of interest was simple: to make sure there were no unfavorable stories about South Korea's dispatching of troops to Vietnam.

The dispatching of troops to Vietnam was a matter directly linked to economic interests, represented by the Brown Memorandum. The Brown memorandum was the U.S. government's promise of 14-point compensation through Brown, U.S. Ambassador to South Korea, on March 7, 1966, in exchange for Seoul's dispatching of additional troops for the Vietnam War. The U.S. government would not only shoulder the cost of sending troops, but also support the modernization of the South Korean military equipment. It would also enable participation of South Korean vendors in various projects in Vietnam by providing loans and military aid. This memorandum was about to be brought to light at the Symington hearing. The South Korean government was highly alert. The following telegram from the South Korean ambassador to the U.S. that was sent to the South Korean Minister of Foreign Affairs accurately portrays the government's concerns that the release of the Brown memorandum may reduce or cut off U.S. military assistance to South Korea.

It is expected that the South Korean military will be criticized by the Symington subcommittee for reaping excessive economic gains by dispatching troops to Vietnam. The U.S. administration plans to deny such allegations and advocate continued financial support to the South Korea to the best of its abilities. (...) (from a telegram in January of 1970, exact date unknown); We made it clear to Ambassador Brown (who served as U.S. ambassador to South Korea in 1966 and was among the main players of the Brown Memorandum. Transferred in 1970 to serve as assistant secretary of state for the Asia Pacific regions) that we don’t want the release of the memorandum to signal that South Korea dispatched mercenary troops to Vietnam. Brown acknowledged such concerns and said he would do his best to prevent any damage to the reputation of both countries. (in a telegram dated January 23, 1970).

There was another variable here: the alleged atrocities by the South Korean military, and the fact that it might be brought up at the Symington hearing. In fact, on February 17, 1970, the Secretary of State sent a telegram inquiring about the mishap of the South Korean military in Vietnam," to the Secretary of Defense, saying “The U.S. State Department expects there to be questions about alleged mishaps, including atrocities by the Korean military in Vietnam, during the upcoming Symington hearing.[2] We have requested the U.S. Embassy in South Vietnam to review the details of our disciplinary actions and, in the event of any disciplinary action, to send us data on such actions. So we ask for your prompt attention to this matter."

It was as predicted. Since December of 1969, letters were exchanged between the U.S. State Department and the Pentagon and the U.S. Embassy in South Vietnam over alleged atrocities by South Korean troops. The names Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất repeatedly appeared in the correspondence.

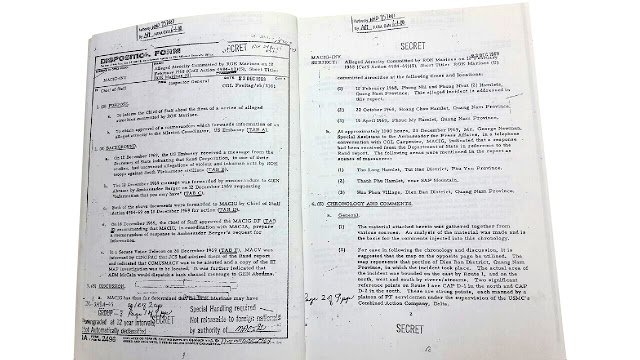

On December 18, 1969. Colonel Sam H. Sharp of the Inspection Department of the U.S. Army Command in Saigon, South Vietnam, submitted a secret report to Major General Ellas C. Townsend, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army Command. It was titled, "Suspicion of atrocities committed by South Korean Marines on February 12, 1968.” This was not the only case. On January 10, 1970, Colonel Robert Cook, another senior officer at the U.S. Army inspection division, handed over a secret report to the chief of staff, titled, "Suspicion of cruelty by South Korean marines on April 15, 1969.” The next day on January 11, Colonel Cook sent another report of a different incident to the same superior. It was titled, "Suspicion of atrocities committed by South Korean Marines on October 22, 1968,” and contained similar information with only a different date."

All three incidents took place in Vietnam's central province of Quang Nam, with Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất in Điện Bàn District on February 12, Phước Mỹ in Duy Xuyên District on April 15, and Hoàng Châu Village on Oct. 22. The report on the investigation into the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất villages shows statements by U.S. soldiers, South Vietnamese militia, residents of the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất villages, and commanders of the South Vietnamese army, as well as correspondences between Westmoreland, Commander of the U.S. forces, and General Chae Myung-shin and the photographs of the victims that a U.S. soldier took. What remains unknown is why the U.S. Army Command collected information on these incidents and reported them to the top.

U.S. military secret report on the atrocities committed by the Korean troops stationed in Vietnam. The U.S. government and the U.S. military command seem to have been worried since December of 1969 that the document might be disclosed during the upcoming Symington hearing.

It all resulted from a report by the RAND Corporation[3], a U.S. think tank. In July 1968, the RAND Corporation published a report titled, "Political Motivation of the Viet Cong" under the service of the U.S. Department of Defense. It said that hundreds of civilians in Vietnam's Phú Yên Province were killed by South Korean troops in mid-1966. On December 12, 1969, the U.S. State Department notified the U.S. Embassy in Saigon of this, and Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker circulated the document to Abrams, commander of the U.S. Army in Vietnam. In the process, the U.S. State Department asked the U.S. military command via the embassy to inform it of whether there is any additional information related to the South Korean military's atrocities. What came out of the process were three investigative reports, including the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất incident of February 12, 1968.

On January 10, 1970, U.S. Secretary of State William Rogers said in a full text sent to the embassy. "Were we aware of these suspicions in advance, did we investigate them, if not, why hadn’t we, and did we conclude that these suspicions were true? If so what measures have we taken against the Koreans to rectify the situation, and to what extent can we talk to the press about these facts?" The State Department also said a day later, sending a full text to the U.S. Embassy in Seoul on January 11, "Do not let reports on incidents involving the Korean military be made public."

The part about not letting any of it leak into media reports is due to an article in the New York Times. On January 12, the New York Times introduced a RAND report detailing the fact that a high-ranking general of the U.S. Army Command stopped investigating the South Korean military. As if it had prior knowledge on the report, the U.S. State Department published all the points that concerned the U.S. government on January 10, stating that the joint concern of the State and Defense Department is the U.S. Army Command’s attempted cover-up of the incident. This accusation could be unleashed through the Symington hearing on South Korea, which was to begin on February 24. The U.S. and South Korean governments, amid the dirty revelations of war, had to prevent the aftershocks from the My Lai incident from shifting over to the South Korean military and its atrocities.

Perhaps due to the success of the cover-up efforts, information on the three additionally reported cases, including that of Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất, was no longer disclosed to the U.S. media. Only the Korean media briefly reported control comments about the New York Times article.

Regarding some foreign media reports that the South Korean Marine Corps committed what it called atrocities against civilians in Vietnam in 1966, Defense Ministry spokesman Roh Young-seo said, "We find these reports deeply regrettable, given that they greatly damaged the honor and national prestige of the entire South Korean armed forces, including the South Korean military in Vietnam." In the statement, Roh said, "The account of atrocities committed by the Korean military reported by some foreign news outlets is based simply on statements and rumors by refugees in South Vietnam, and this is of no value except to undermine the joint efforts of the coalition and to benefit the enemy." (Kyunghyang Shinmun, dated January 16, 1970).

They managed to evade any consequence. There was no attack by lawmakers at the Symington hearing that left the South Korean government feeling anxious. Based on what was reported to the prime minister of state affairs and the president after the hearing on March 2, 1970, the hearing proceeded in an amicable manner. There were questions regarding U.S. defense commitments to South Korea--on whether the U.S. policy on Korea was appropriate in terms of its own capabilities. Of course, one of the four items cited from the hearing included the investigation on the atrocities committed by South Korean troops in the Vietnam War per J. W. Fullbright, whose name is widely known in Korea for the "Fullbright Scholarship." However, this was with respect to what had been reported in the January 12th edition of the New York Times, which shed no light on the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất case that was being further investigated by the U.S. Army Command. Either way, the answer would have been obvious--comparable to the aforementioned comment made by the South Korean Defense Ministry in the Kyunghyang Shinmun.

President Park Chung-hee may have known in advance that the U.S. Army Command in Vietnam was asked by the State Department to provide additional information on the Korean military’s atrocities around December 12, 1969. It was a time when official documents were actively being exchanged among the State Department, the Department of Defense and the U.S. Embassy in Vietnam. If so, already by November 1969, about a month before all this, Park was likely to have received information about the matter from behind the scenes through the Korean Military Command in Vietnam or the Central Intelligence Agency.

One could still only surmise, but of the three incidents investigated by the U.S. Army Command, the most potentially destructive was the one of Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất. The number of victims was the highest at around 70, and the U.S. military's investigation report was the most specific. "The Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất case should not be a stumbling block to the hearing in February 1970." The reason that the Marines who entered the town of Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất in November 1969 were investigated at the Central Investigation Agency was probably Park Chung-hee's premonition that it would later become a hindrance.

[1] From "Symington hearing, 1970. Pre- volume 2, and V.1 Basic Documentary," Correspondence between Foreign Minister Choi Kyu-ha and Deputy U.S. Ambassador in South Korea, Lathram (preservation of diplomatic historical records).

[2] Pre-volume 2 and V.1 Basic Documentary' (preservation of diplomatic archives).

[3] RAND(Research and Development) Corporation . The first full-fledged think tank in the U.S., established in 1948 with the support of the U.S. Air Force. It has researchers in a wide range of fields, including engineers, mathematicians, physicists, programmers, meteorologists, economists, historians, psychologists, and sociologists, and others, and is conducting basic research on international, military, and domestic affairs. It also participated in the system development for the first satellite launched in 1958.

- Written by humank (Journalist; Seoul, Korea)

- Translated and revised as necessary by April Kim (Tokyo, Japan)

The numbers in parentheses indicate the respective ages of the people at the time in 1968.