27. Treated Like Insects

Precursor to the Mỹ Lai Massacre: 1968 Phong Nhị, Phong Nhất_27: Treated Like Insects

Click to read in Korean(박정희는 왜 특명을 내렸나)

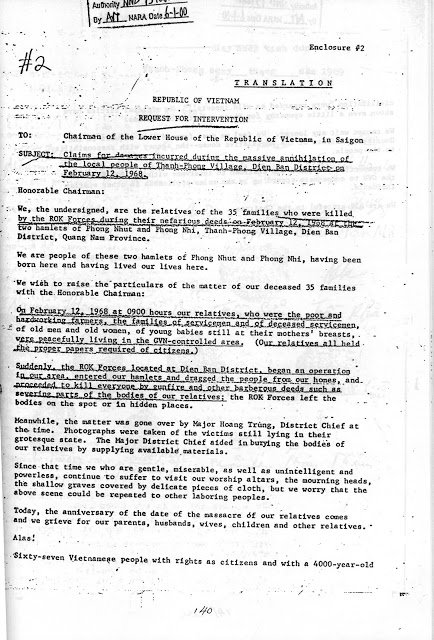

TO : Chairman of the Lower House of the Republic of Vietnam, in Saigon

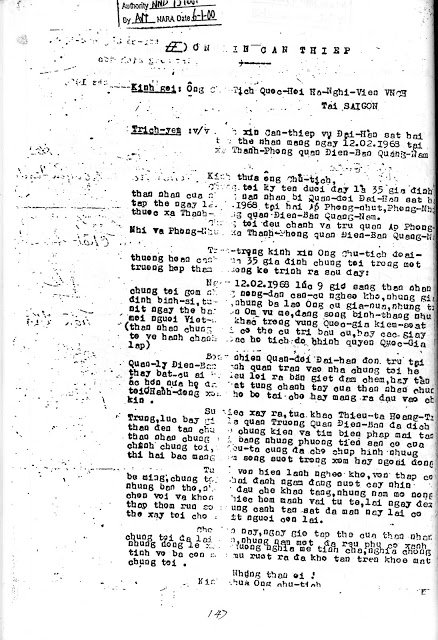

SUBJECT : Claims for damages incurred during the massive annihilation of the local people of Thanh-Phong Village, Điện Bàn District on February 12, 1968.

Honorable Chairman :

We, the undersigned, are the relatives of the 35 families who were killed by the ROK Forces during their nefarious deeds on February 12, 1968 at the two hamlets of Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất , Thanh-Phong Village, Điện Bàn District, Quang Nam Province.

We are people of these two hamlets of Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất , having been born here and having lived our lives here.

We wish to raise the particulars of the matter of our deceased 35 families with the Honorable Chairman :

On February 12, 1968 at 0900 hours our relatives, who were the poor and hardworking farmers, the families of servicemen and of deceased servicemen, of old men and old women, of young babies still at their mother’s breasts, were peacefully living in the GVN-controlled area. (Our relatives all held the proper papers required of citizens.)

Suddenly, the ROK Forces located at Điện Bàn District, began an operation in our area, entered our hamlets and dragged the people from our homes, and proceeded to kill everyone by gunfire and other barbarous deeds such as severing parts of the bodies of our relatives: the ROK Forces left the bodies on the spot or in hidden places.

Meanwhile, the matter was gone over by Major Hoang Trung, District Chief at the time. Photographs were taken of the victims still lying in their grotesque state. The Major District Chief aided in burying the bodies of our relatives by supplying available materials.

Since that time we who are gentle, miserable, as well as unintelligent and powerless, continue to suffer to visit our worship altars, the mourning heads, the shallow graves covered by delicate pieces of cloth, but we worry that the above scene could be repeated to other laboring peoples.

Today, the anniversary of the date of the massacre of our relatives comes and we grieve for our parents, husbands, wives, children and other relatives.

Alas!

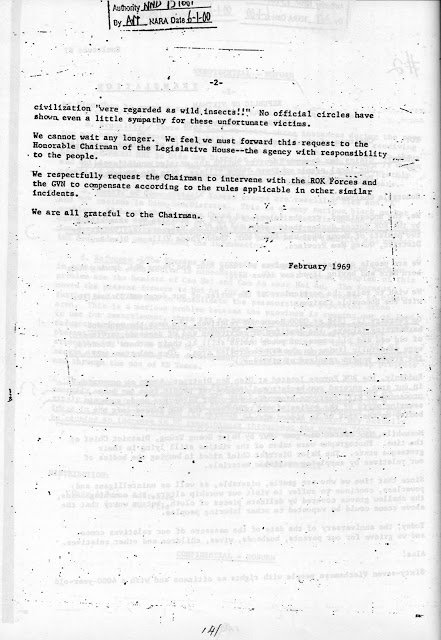

Sixty-seven Vietnamese people with rights as citizens and with a 4000-year-old civilization “were regarded as wild insects!!” No official circles have shown even a little sympathy for these unfortunate victims.

We cannot wait any longer. We feel we must forward this request to the Honorable Chairman of the Legislative House—the agency with responsibility to the people.

We respectfully request the Chairman to intervene with the ROK Forces and the GVN to compensate according to the rules applicable in other similar incidents.

We are all grateful to the Chairman.

February 1969

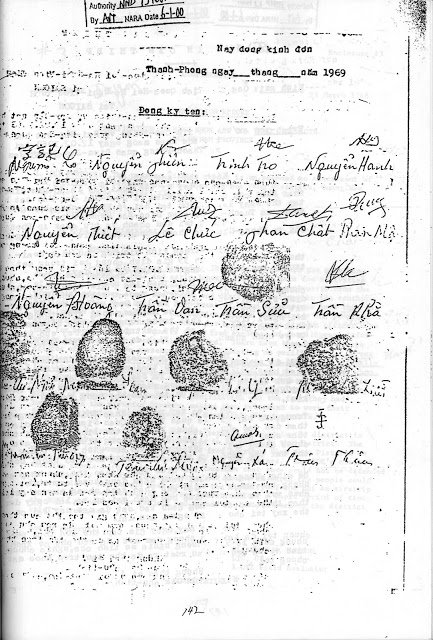

February 12, 1969 marked the first anniversary of the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất incident. Thirty-five bereaved families whose family members were killed in the massacre sent a petition demanding compensation to the chairman of the South Vietnamese House of Commons in Saigon. More than 20 people wrote down their names and sealed it with their thumbprints. The bereaved families expressed their anger and sadness, saying 67 Vietnamese human beings were treated like insects by the South Korean soldiers.[1] The petition, attached to an internal U.S. military document that was declassified in 2000, was originally written in Vietnamese, but the U.S. military also translated it into English. There is no way to know, however, who led the creation of the petition or whether it was actually delivered to the chairman of the House of Commons in Saigon. The same is true of what category of "damage compensation" was demanded by the victims' families. According to an investigation by the U.S. military authorities, a senior staff member of the 1st Battalion of the 2nd Brigade of the Marine Corps called in Major Hoang Truong, the commander in charge of the South Vietnamese military in the Điện Bàn District, and provided him with 30 sacks of rice shortly after the February 12 incident in 1968.[2]

Memorial Monument for the victims of February 12, 1968 at the entrance of Phong Nhị. The names, ages and addresses of 74 people are inscribed. This photograph was taken in February of 2018. One could see the names of the youngest victims who were born in 1967 and 1968 on the lower part of the monument. The dolls with the names of the victims in front were made by members of a Korean youth organization called Vietnam Friends. Photograph by Koh Kyoung-tae

Lieutenant Choi Young-un, the commander of the 1st platoon of the 1st company who first entered the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất villages on the morning of February 12, 1968, was in Pohang, South Korea, a year later in February of 1969. The deployment period to Vietnam was usually one year. He and most other members of the 1st company had returned to Korea. The day Choi returned to the port of Busan aboard a transport ship from Danang was Christmas Eve, December 24, 1968. His hometown Busan was where he was born and raised. He took a taxi to meet a friend who ran a bookstore in Gwangbok-dong. His friend who was organizing a bookshelf greeted him with surprise. It was sub-zero weather, but Choi’s battle uniform, with its sleeves cut off with scissors, was nothing short of summer attire. Only the white of his eyes and his teeth glowed against the tanned skin of the Marine officer who had just returned from the tropics. Choi drank soju with his friend at a bar in Nampo-dong. Those sitting in nearby tables poured shots for Choi in celebration of his safe return to his home country. Choi’s friend seemed to be proud to have such a friend.

His homecoming did not mean immediate discharge, however. The Marine Corps command extended the service period of its officers from three to five years, citing a lack of Marine officers due to the dispatch of troops to Vietnam. Since Choi joined in March 1966, there still remained two years until he would be discharged in March 1971. He headed for Busan station the next morning. He had to take a military train to the headquarters of the Marine Corps' Pohang Landing Post. On the day that he reported his return, Kim Yeon-sang, commander of the landing post, learned that Lieutenant Choi had lived in a confinement facility for 45 days for a misdemeanor before going to Vietnam.[3]

Choi led the marine cadets in the attack on the Gimhae aviation school on Aug. 7, 1966. He nonetheless considered it an honor. "You’re back from Vietnam, so go get some rest," the commander said to Choi. Lieutenant Choi was then ordered as deputy principal of the field sanitation school. It was a bit of a leisurely post. He remained there in February of 1969 as well.

President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu of South Vietnam landed at Gimpo Airport at 3:00 p.m. on Thursday by special plane with his wife to make an official four-day visit to Korea at the invitation of President Park Chung-hee and his wife. Thiệu, who was the second Vietnamese president to visit South Korea after former President Ngo Dinh Diem, attended the welcoming ceremony soon after being greeted at the airport by Park Chung-hee and his wife, as well as key figures and foreign diplomats, who held a tri service honor guard ceremony with 21 gunshot salutations to welcome him.

President Park's welcoming speech included the following points: South Korea and South Vietnam share a special friendship in that they are both divided, yet free-for-all nations fighting their respective communist counterparts, and this is why South Korea has dispatched troops to fight for South Vietnam’s cause. As South Vietnam is coming into a new phase of seeking honorable peace amid the whirlwind of repeated battles and negotiations, its concern is shared by the Korean people, who feel its pain as if it were their own and directly link the future freedom of South Vietnam with the anti-communist future of South Korea. As such, it is more imperative than ever that in a time like this, that the two countries further strengthen their bond of solidarity and cooperation, and further forge the resolve of joint efforts toward the same goal (Dong-A Ilbo, May 27, 1969).

President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu had come to Korea. He was one of the main forces in the military coup that assassinated President Ngo Dinh Diem and seized power on November 11, 1963. Thiệu, who was elected president of the Constitutional Council for the Advancement of Civil Affairs on September 3, 1967, visited Korea for the first time since he took office on May 27, 1969. After wrapping up his four-day trip, he issued a joint statement with South Korean President Park Chung-hee on his way to Taiwan. Until peace was secured in the South, the two countries agreed that they would join military and diplomatic efforts without unilateral withdrawal and work toward strengthening cooperation between the two nations. The biggest topic between Park Chung-hee and Thiệu was the "honorable end of the war." In Paris, France, peace talks were underway over Vietnam's cease-fire. Nevertheless, the U.S. bombing of Northern Vietnam was still continuing.

Choi Young-un's post changed around the time of Thiệu's visit to Seoul. He was the Lieutenant General and Chief of Security Command at the headquarters of the Landing Post Command in Pohang. It was a powerful position in charge of prisons, military police and even PXs in the division. Originally, a senior captain was supposed to assume this position, but they lacked officers at the time. Choi was therefore temporarily assigned the rank of captain. To him, Thiệu's visit to Korea seemed to be nothing more than a passing incident.

The Sơn Mỹ or “My Lai” Massacre incited by the U.S. military in late March of the previous year in Quang Ngai Province was gradually surfacing, stirring public sentiment both within and outside the U.S. In addition, the Pentagon was reported to have launched an investigation after receiving information that another massacre took place near the "Dongtap" village last summer, raising the voices of criticism against the conscience of the United States.

The U.S. military's "Sơn Mỹ" massacre, which was reported by the New York Times on Thursday, came to light as the U.S. military took a 26-year-old lieutenant named William Calley, who appeared to be the leader of the massacre, to military court on Monday for premeditated murder. Lieutenant Calley’s charge was that he killed at least 109 civilians, including women, in the Sơn Mỹ Village, located in South Vietnam on March 16, 1968 (Dong-A Ilbo, November 29, 1969).

The coverage of the My Lai incident by U.S. local media such as the New York Times wasn’t exclusive, as the Dong-A Ilbo had reported on it as well. On November 12, 1969, independent investigative journalist Seymour Hershey first reported it to the world through a small Washington news agency, the Dispatch News Service. Not only AP and The New York Times, but also magazines such as Life, Time, and Newsweek followed suit, and made a big deal of the incident. Shock resonated throughout. On March 16, 1968, 504 elderly people, women and children were killed in central Vietnam by the U.S. military's firing at Sơn Mỹ County, in Quảng Ngãi Province, Sơn Tịnh District.

A petition sent to the chairman of the Vietnamese House of Commons in February of 1969, a year after the incident. The document, written in Vietnamese, was also translated into English, but remained classified in the U.S. National Archives until 2000 when it was declassified and was first reported in November of 2000 through the Korean weekly current events magazine <Hankyoreh 21>.

Charlie Company of the 1st battalion of the U.S. Army's 23rd Infantry Division's 11th Regiment was responsible for the massacre. The person who received the spotlight for his misdeeds was Lieutenant William Calley (1943~ ) who was the first platoon leader of Charlie Company. He shot unconditionally at the civilians in the village, despite that they were not in possession of weapons or even being hostile towards them. The platoon members followed suit. A few days ago, five of their colleagues had been killed by booby traps, and though they were rightfully incited by hostility, it did not justify their actions.

The 23rd U.S. Army Division was called the "Americal Division." Their operational area in Sơn Mỹ, Quảng Ngãi Province was originally the operational area of the 2nd Brigade of the Korean Marine Corps when they were stationed in Chu lai (August 1996-1967). According to one statistic, during the one-year period from September 1966 to September 1967, the 2nd Brigade of the South Korean Marine Corps killed as many as 1,000 civilians in 13 areas, including the villages of Phước Bình and Diên Niên in Sơn Thịnh District, to which My lai belonged as well.[4] The 2nd Brigade of the Marine Corps handed over the area to the Americal Division as it moved to Hoi an, and My lai, which was lucky to have evaded the hands of the South Korean military, ended up becoming a victim of the U.S. military instead.

Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất were often called different names by South Korean marine officers: "the Korean version of My lai" or "Another My lai." The unfolding of the My lai incident was enough to make the South Korean soldiers who have already been to Vietnam feel a sense of dejavu. The My lai incident was extremely similar to that of Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất in that they were both brought to light, failing to remain a perfect crime.

Of course there were also differences. The firing from My lai was carried out systematically from the cavalry platoon (1st platoon) that arrived in the area. Meanwhile, there are strong suspicions that in the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất incident, the shootings happened accidentally among the 3rd platoon, after the 1st and 2nd platoons had already entered earlier. When pictures of Lieutenant William Calley on military trial for the My lai case were being reported by local media, Lieutenant Choi, among other sergeants and soldiers who had entered the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất villages, was being questioned by the Central Intelligence Agency. The Central Intelligence Agency investigator had indicated that the president is inquiring to know the truth. Perhaps President Park Chung-hee, after seeing the Nixon administration on the defensive due to the My lai incident, decided to investigate the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất incident in order to preemptively block a similar crisis.

Perhaps he sensed that My lai may be more pertinent than meets the eye. There was another incident that indicated as much, namely, the statement by the representative of North Vietnam at the Paris peace talks for the Vietnam War in November 1969. It was the first time that bilateral talks between the U.S. and North Vietnam were expanded to four-way talks involving the South Vietnamese government and the South Vietnamese Provisional Revolutionary Government formed by the Viet Cong. Various foreign media's attention was honed in on this event. Referring to the U.S. military's My lai incident on November 26, the North Vietnamese representative claimed that the South Korean military also massacred more than 700 civilians in the Northern region (now in the central region), a statement that made its way into foreign media reports. As a rebuttal for its defense ministry, the South Korean media reported that it was a malicious false propaganda aimed at alienating the South Korean people from the Vietnamese people, and that it was not even worth a thought (The Dong-A Ilbo newspaper, front page of November 26, 1969 , “The mass killing by the South Korean soldiers, false propaganda on the communist side”). The significant point here is that when the North Vietnamese representative pointed out in what areas that civilians were killed, he mentioned Dien An, to which both Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất belong. This would have been enough to put President Park Chung-hee on edge.[5]

By the time he was going to the Central Intelligence Agency to be questioned, Lieutenant Choi Young-un's post had been changed again. He was no longer commander of the headquarters and commander of the company guards, but instead the assistant training officer at the shooting range. Upon hearing from the Central Intelligence Agency that this was a special investigation directed by the president, Lieutenant Choi belatedly recalled President Thiệu’s visit to Seoul six months ago, as there was a particular rumor floating around among the Marine officers. It was that President Thiệu, who visited Seoul and held summit talks with President Park Chung-hee, made an unofficial protest over the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất incident, turning it into a diplomatic issue between South Korea and Vietnam. It all seemed like a plausible scenario given the My lai incident, the remarks of the North Vietnamese representative at the Paris Peace Conference, and the Central Intelligence Agency's investigation. Perhaps the fundamental force behind the president’s special investigation was simply a petition sent to the House of Commons by the bereaved families of the victims of the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất villages in February 1969, though there is no evidence to confirm whether this is true or not .

In addition to the petition by the families of the victims of the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất villages, President Thiệu's visit to Korea, and the My lai incident, there was one more event. It was highly likely that President Park Chung-hee, who even ordered a special investigation, foresaw the signs of something. A month later, the signs began to come true.

[1] The total number from the 2004 death toll by the People's Committee of the Điện An was 74 .

[2] General Chae Myung-shin, commander of the South Korean military, dismissed the report saying it doesn’t make sense to link the delivery of relief supplies to the Phong Nhị incident.

[3] Kim Yeon-sang was the commander of the 2nd Brigade of the South Korean Marine Corps stationed in Hoi An at the time of the Feb. 12, 1968.

[4] * 'Statistics of the massacre of civilians by Korean soldiers during the Vietnam War' (released by Koo Su-jeong's Jeju Conference on Human Rights, February 2000).

[5] Although it was called Thanh-Phong at the time, it is possible its old name, Dien, which was given before the establishment of South Vietnam was used. The Ministry of Defense lied saying "Dien An" is not within the Blue Dragon unit's tactical area.

- Written by humank (Journalist; Seoul, Korea)

- Translated and revised as necessary by April Kim (Tokyo, Japan)

The numbers in parentheses indicate the respective ages of the people at the time in 1968.