26. The Cruel Conspiracy of the Viet Cong

Precursor to the Mỹ Lai Massacre: 1968 Phong Nhị, Phong Nhất_26: From Chae Myung-shin to Westmoreland

Click to read in korean( 덕장의 위장술)

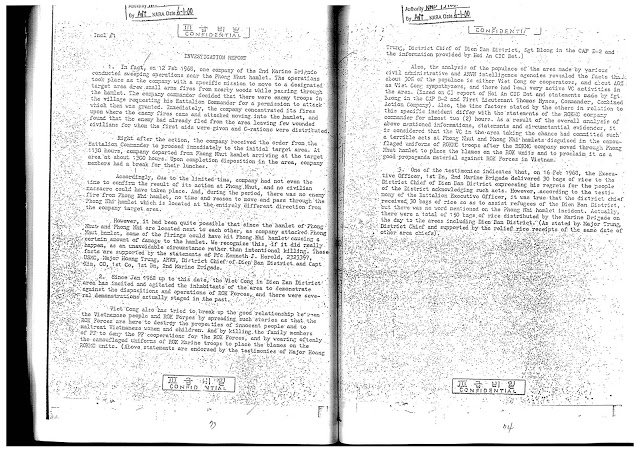

Since Jan 1968 also has tried to break up the good relationship between the Vietnamese people and ROK Forces by spreading such stories as that the ROK Forces are here to destroy the properties of innocent people and to maltreat Vietnamese women and children. And by killing the family members of PF to deny the PF cooperations for the ROK Forces, and by wearing oftenly the camouflaged uniforms of ROK marine troops to place the blames on the ROKMC units. (Above statements are endorsed by the testimonies of Major Hoang Trung, District Chief of Dien Ban District, Sgt Blong in the CAP D-2 and the information provided by Hoi An CIC Det.) (……) Also, the time factors stated by the others in relation to this specific incident differ with the statement of the ROKMC company commander for almost two (2) hours. As a result of the overall analysis of above mentioned informations, statements and circumstantial evidences, it is considered that the VC in the area taking the chance had committed such a terrible acts at Phong Nhut and Phong Nhi hamlets disguised in the camouflaged uniforms of ROKMC company moved through Phong Nhut hamlet to place the blames on the ROK units and to proclaim it as a good propaganda material against ROK Forces in Vietnam.

In May of 1968, the scorching sun in central Vietnam was unbearable. Sung Baek-woo (31), chief investigator of the 2nd Brigade of the Marine Corps in Hoi an, wiped sweat off his face as he read through the report. It contained the results of an investigation into the alleged atrocities committed by the South Korean troops in the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất villages of Điện Bàn District, Quangnam Province, three months ago on February 12. It was written by the 2nd Brigade of the Marine Corps and was waiting to be reported. Upon orders from Major General Park Young-gil, the head of the military police, Sung had become involved in the process.

Major Park Young-gil called him quietly a month ago and said an order for a fact-finding mission came from the top. From the look of it, the situation seemed anything but simple. According to an earlier U.S. military investigation report, more than 60 civilians were found dead that day after the South Korean troops passed through the area. The U.S. military went to the scene of the incident and provided first aid care to the wounded. The residents who survived the incident petitioned to the Quangnam Provincial Office, asking for the punishment of the soldiers. The U.S. military and the South Vietnamese government were involved, which made it difficult to simply sweep under the rug. Chae Myung-shin, commander of the South Korean military, had no choice but to order an investigation to the 2nd brigade headquarters, as he had received a formal request for action from Commander Westmoreland of the U.S. Army. This eventually led to an overseas investigation by the military police sergeant Sung.

The only two remaining investigators at the brigade headquarters' military police were Lieutenant Colonel Sung and another noncommissioned officer. Originally, there were six, but four were dispatched to the battalion. For the next two weeks or so, the two military police investigators visited officers and soldiers of the first company of the first battalion who were operating in Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất on February 12. They began writing their report based on the testimonies of the 2nd company commander Lee Sang-woo and other members of the company. 1st battalion commander Hong Sung-hwan and 1st company commander Kim Seok-hyun were even called back to Vietnam for the investigation.

The military commanders of the three countries, Chae Myung-shin of the South Korean military, Viên of the South Vietnamese military, and Westmoreland of the U.S. military, holding operational meetings. Photograph from, "The Memoirs of Chae Myung-shin - The Vietnam War and I" (above) In the spring of 1968, the 1st company on an operation using Caliber 30 machine guns near Điện Bàn . (upper right) The 1st company returning to their base after the operation. The civilians made way for them by stepping off to one side of the road (lower right).

They were asked how, when and where they carried out their operation on February 12. They were also asked to confirm whether guns were pointed at civilians. Most of the officers said they have no recollection of firing guns at civilians and that if it happened at all, it was the work of the Viet Cong. Sung had them read the report he composed and seal it with their thumbprints. He was now reading the report summarizing the investigation, which concluded the following:

"As a result of the overall analysis of above mentioned informations, statements and circumstantial evidences, it is considered that the VC in the area taking the chance had committed such a terrible acts at Phong Nhut and Phong Nhi hamlets disguised in the camouflaged uniforms of ROKMC company moved through Phong Nhut hamlet to place the blames on the ROK units and to proclaim it as a good propaganda material against ROK Forces in Vietnam."

Sergeant Sung Baek-woo was dismayed. If he were asked whether the investigation report he had helped prepare was true, he would have to shake his head, no. From the get go, an investigation to shed light on the truth wasn’t going to happen. Even Major General Park Young-gil, as he ordered the investigation, instructed Sung to just follow guidelines. And the guidelines were consistent with the testimony of the 1st Company who claimed to have never massacred the people and that it was just the work of the Viet Cong disguised in South Korean military camouflage suits. The investigation was in a sense rigged. He just didn’t know whose idea it was to blame the Viet Cong.

General William C. Westmoreland

Commander

United States Military Assistance Command

Saigon, Vietnam

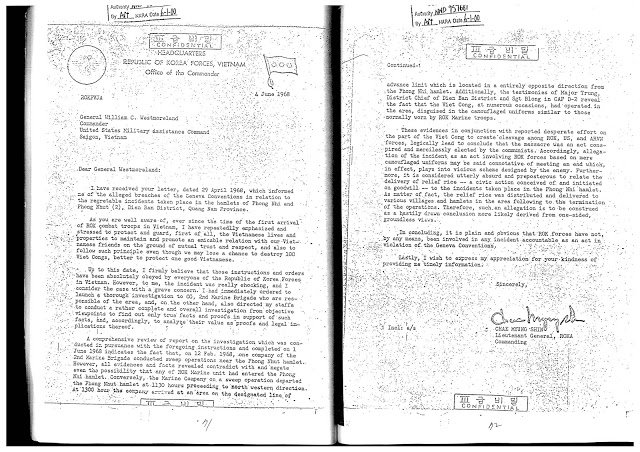

Dear General Westmoreland

I have received your letter, dated 29 April 1968, which informed me of the alleged breaches of the Geneva Conventions in relation to the regrettable incidents taken place in the hamlets of Phong Nhi and Phong Nhut (2), Dien Ban District, Quang Nam Province.

As you are well aware of, ever since the time of the first arrival of ROK combat troops in Vietnam, I have repeatedly emphasized an stressed to protect and guard, first of all, the Vietnamese lives and properties to maintain and promote an emicable(amicable로 정확할 듯) relation with our Vietnamese friends on the ground of mutual trust and respect, and also to follow such principle even though we may lose a chance to destroy 100 Viet Congs, better to protect one good Vietnamese.

Up to this date, I firmly believe that those instructions and orders have been absolutely obeyed by everyone of the Republic of Korea Forces in Vietnam. However, to me, the incident was really shocking, and I consider the case with a grave concern. I had immediately ordered to launch a thorough investigation to CG, 2nd Marine Brigade who are responsible of the area, and, on the other hand, also directed my staffs to conduct a rather complete and overall investigation from objective viewpoints to find out only true facts and proofs in support of such facts, and accordingly, to analyze their value as proofs and legal implications thereof.

A comprehensive review of report on the investigation which was conducted in pursuance with the foregoing instructions and completed on 1 June 1968 indicates the fact that, on 12 Feb 1968, one company of the 2nd Marine Brigade conducted sweep operations near the Phong Nhut hamlet. However, all evidences and facts revealed contradict with and negate even the possibility that any of ROK Marine unit had entered the Phong Nhi hamlet. Conversely, the Marine Company on a sweep operation departed the Phong Nhut hamlet at 1130 hours proceeding to north western direction. At 1300 hour the company arrived at an area on the designated line of advance limit which is located in a entirely opposite direction from the Phong Nhi hamlet. Additionally, the testimonies of Major Trung, District Chief of Dien Ban District and Sgt Blong in CAP D-2 reveal the fact that the Viet Cong, at numerous occasions, had operated in the area, disguised in the camouflaged uniforms similar to those normally worn by ROK Marine troops.

These evidences in conjunction with reported desperate effort on the part of the Viet Cong to create cleavage among ROK, US, and ARVN forces, logically lead to conclude that the massacre was an act conspired and mercilessly elected by the communists. Accordingly, allegation of the incident as an act involving ROK forces based on mere camouflaged uniforms may be said connotative of meeting an end which, in effect, plays into Vicious scheme designed by the enemy. Furthermore, it is considered utterly absurd and preposterous to relate the delivery of relief rice—a civic action conceived of and initiated on goodwill—to the incidents taken place in the Phong Nhi hamlet.[1] As matter of fact, the relief rice was distributed and delivered to various villages and hamlets in the area following to the termination of the operations. Therefore, such an allegation is to be construed as a hastily drawn conclusion more likely derived from one-sides, groundless views.

In concluding, it is plain and obvious that ROK forces have not, by any means, been involved in any incident accountable as an act in violation of the Geveva Conventions.

Lastly, I wish to express my appreciation for your kindness of providing me timely information.

Sincerely,

CHAE MYUNG SHIN

Lieutenant General, ROKA

Commanding

A document (above) by Chae Myung-shin, commander of the South Korean Army, responding to the U.S. military commander Westmoreland’s demand to explain the massacre of civilians, and the Korean military's Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất Incident Investigation Report (below).

Lieutenant General Chae Myung-shin, commander of the South Korean military, did a final review of the letter before signing it. It had already been 36 days since he received a letter from General Westmoreland. The document was based on an investigation report that Sung Baek-woo, a sergeant of the 2nd Brigade of the Marine Corps' Military Police Corps, helped compose. He smiled contentedly, now feeling relief from the discomfort he had initially felt since he first received a letter from General Westmoreland demanding action with respect to the South Korean military. He felt he could now fathom how events unfolded in Phong Nhị that day. General Chae Myung-shin imagined the Viet Cong disguised in Korean uniforms and thought this was the essence of guerrilla warfare. At the same time, he felt oddly nostalgic. The Vietnam War, which he was called to as commander of the Korean Army with stars, and the Korean War, which he fought as a field-grade officer, merged into one in his head. As he envisioned a Viet Cong in a Korean military uniform, an image of himself in a North Korean People's Army uniform overlapped with the image.

In late January of 1951, when the Korean War was in full swing, lieutenant colonel Chae Myung-shin led around 300 junior soldiers and infiltrated the mountainous region of Yeongwol, Gangwon Province. It was the "11th Regiment of Diversion attack" that was later expanded and reorganized into the "White Bone Corps." They were all dressed up as the People's Army, carrying Soviet-made AK47s and carrying North Korean currency. It was a large regular guerrilla force tasked with disrupting the Chinese and North Korean forces from behind after the retreat in 1951 caused by the unexpected intervention of Chinese forces. Chae Myung-shin was their commander. Right after the Incheon Landing in September 1950, he went up to Deokcheon, South Pyongan Province, as the first battalion commander of the 21st Regiment, and after the intervention of the Chinese Air Force, he was almost taken as a prisoner of war but he fought tooth and nail to make his way back to the south. However, he volunteered to lead guerrilla forces and was on his way back to the North.

Chae Myung-shin, acting as lieutenant colonel of the North Korean People's Army, unabashedly traveled to the eastern mountainous region on the upper part of Mount Odae, battling through snow piling up more than a meter high and frigid temperatures of -20°C. When he ran into a unit in the People's Army, he would beat them to the punch by asking, "Comrades, which way are you headed?" Chae was born in Goksan, Hwanghae Province in 1926, and spent more than 20 years in North Korea until he escaped from Christian oppression in February of 1947, so his accent was natural. North Korean soldiers completely fell for his confidence when claiming he was from the central party and were immediately disarmed, even saluting Chae with utmost courtesy. When he crossed paths with the 69th Brigade Command liaison officers who were on their way to the 2nd Infantry Division headquarters with classified documents, he took their clothes and went to the headquarters and exterminated their guard posts.

Sung Baek-woo, chief investigator of the 2nd Brigade of the Marine Corps. He took part in writing a report on the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất incident.

The capturing of Kim Won-pal, the commander of the north’s guerrilla forces, was his most brilliant achievement in all of his experience disguising as the enemy in the past. In October of 1949, right before the Korean War, when he was the commander of the 2nd Company of the 1st Battalion of the 25th Regiment, when he would ransack Mount Taebaek for commies, Chae Myung-shin, disguised in guerrilla uniform, led a squad of troops into civilian houses near Yeongdeok-eup, North Gyeongsang Province, and searched for guerrilla collaborators.

Guerrilla warfare was something of a fate for him. In March of 1948, he was of the 5th graduating class of the National Defense Military Academy (formerly the Military Academy) and was commissioned as a second lieutenant to the post at the ninth regiment of Jeju Island. The first time he set foot in Jeju was on April 6, 1948, three days after the first shooting of the April 3rd incident. At the time, Chae had 42 platoon members under him, mostly from Jeju Island, but sometimes he had trouble telling whether they were subordinates or actually foes. He survived many shooting attacks, overcoming the gruesome and chilling inhumanity of guerrilla warfare with the power of religion.

Chae, who knew guerrilla warfare better than anyone in South Korea, was appointed the commander of the Korean Armed Forces to deal with guerrillas in Vietnam. President Park Chung-hee knew of Chae’s command skills in combat from his Korean War days. Park encouraged Chae, who in April of 1951, was the chief of staff of the Gangneung 9th Infantry Division, but acted as commander of the White Bone Corps' guerrilla unit and returned back intact three months later, whereby Park exchanged his own field jacket for Chae’s bloody jacket.

General Chae Myung-shin was known as a master commander. He was always praised and respected as a brave, knowledgeable, and virtuous leader to his juniors. He joined the May 16 coup d'etat in 1961, but refused to accept any political post and insisted on fighting only in the field. He was an upright man who did not hesitate to speak out even before the president, as he opposed the Yushin Constitution, which later served as a stepping stone to the life-long system implemented by Park Chung-hee.

Even so, no lie could replace the truth. The letter to Westmoreland implicating the Viet Cong was just a figment of imagination that reflected the wishes of the Korean military. The Viet Cong were not at all like Chae's men who disguised themselves in the people's military uniforms and roamed the mountainous regions of the two Koreas during the Korean War.

The letter was postmarked June 4. With less than five days left in office, Commander Westmoreland was unlikely to read the letter. On May 21, Chae Myung-shin held a farewell ceremony for Commander Westmoreland, who was to leave for the post of U.S. Army chief of staff at the training camp of the White Horse Division in Ninh Hòa, where the Korean Army's field command was located. At the ceremony, Westmoreland praised Chae Myung-shin for leading the South Korean military to victory in every large-scale battle against the communist forces in Vietnam. Commander Westmoreland flew to Seoul on May 29 and also met with President Park Chung-hee. Speaking at a dinner meeting at the presidential office, Westmoreland praised the South Korean military for its role in Vietnam, saying, "We have even sent U.S. officers to learn about the superior combat capabilities and skills of the Korean military in Vietnam. Their effort in helping the South Vietnamese people who seek freedom and self-rule is very much like that of a pastor of a church."* Upon returning to Saigon, he left Vietnam on June 9 for the United States.

Commander Chae Myung-shin had no idea just yet. Neither did Commander Westmoreland. That their letters and survey reports circulating among major institutions in Korea and the United States would a year later pose a threat to the presidential office of South Korea.

[1]The attached statement from Major Hoàng Trung, commander of the South Vietnamese Army in Điện Bàn, refutes the following claim in the Survey Report of the US Marine Corps 3rd Landing Army Command on February 12, 1968. “The Executive Officer of the ROK 1st Battalion 2nd Marine Brigade paid a call on me after the Phong Nhi incident and brought from the Koreans 30 bags of rice for those villagers. He said he was sorry about the women and children and that it would not happen again.”

Reference

- Regarding Sung's testimony: "Covering up the massacre of innocent civilians by the Blue Dragon unit" (Hwang Sang-chul) p. 26-27, of Hankyoreh Issue No. 310; 21st, June 1, 2000.

- Regarding details on the major activities and life of General Chae Myung-shin: "Chae Myung-shin's memoirs, Beyond the line of death" (Maeil Kyungjae Newspapers, 1994), and "Chae Myung-shin's memoirs, the Vietnam War and I" (Palbok Won, 2006)

- Lt. Col. Sung Baek-woo, chief of the investigation team of the 2nd Brigade of the Korean Marine Corps, who investigated the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất case in 1968.

- Written by humank (Journalist; Seoul, Korea)

- Translated and revised as necessary by April Kim (Tokyo, Japan)

The numbers in parentheses indicate the respective ages of the people at the time in 1968.