23. A day at the Central Intelligence Agency

Precursor to the Mỹ Lai Massacre: 1968 Phong Nhị, Phong Nhất_23: Who shot whom and why?

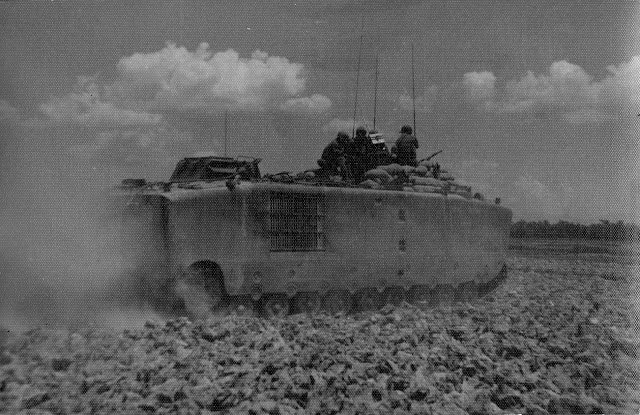

Members of the ROK Marines 2nd Brigade 1st Battalion are traveling in an amphibious armored vehicle (LVT) provided by the U.S. military. Taken in 1968 and owned by 1st platoon commander Choi Young-un.

Click to read in korean( 아무도 쏘지 않았다?)

"You don't have to worry."

The investigator repeatedly reassured him saying not to worry about being put in a disadvantageous position, but to just state the facts based on his experience. The investigator was holding a Vietnam operation map. He opened the map and pointed to an area saying, "So from the number one national highway, you went west, right?"

On a day in November of 1969, Lieutenant Choi Young-un, a 27-year-old marine and assistant to the training officer at the shooting range in the Pohang Landing Post, received a call from a senior Marine Corps officer. "Aboard the Tongil-ho tomorrow, and get off at Seoul Station." In order to get on the Tongil-ho, Choi had to take a bus from Gyeongbuk Pohang and go all the way to Daegu. He showed the station clerk his military stamp for deferred payment and boarded the Gyeongbu Line's northern-bound train. He had no idea why he was being ordered to go to Seoul. When he got off at Seoul Station, ununiformed military police agents who were waiting for him took Choi to the Lions Hotel in Myeong-dong, Seoul. The military police told him that he was going to be investigated but that he shouldn’t worry as it was probably no big deal. Lieutenant Choi stayed overnight at the Lions hotel. As soon as he finished his breakfast the next day, he was guided by the military police to a building across the street. It was the Central Intelligence Agency, which was dubbed “Namsan.”

Lieutenant Choi went into a small room. Across the desk sat two investigators who weren’t overbearing but rather friendly. He felt comforted knowing that they were at least treating him respectfully, as an officer should be treated. The investigators, after asking a few questions, jotted down his answers using a ballpoint pen and paper. Choi couldn’t tell if he was being recorded however.

Investigator: You served as the first platoon commander of the1st company of the Marine Corps 2nd Brigade in Vietnam in February 1968, correct?[1]

Lieutenant Choi: Correct.

Investigator: We are investigating the incident that took place in the operational area of Vietnam on February 12, 1968. (Handing him a map) That morning, the 1st platoon was traveling westward on the number one national highway in Quang Nam, near Hoi An. Can you tell us what happened?

Lieutenant Choi: That day when we were passing the village, the first platoon was at the forefront. We marched in indian file, with myself in the middle. We suddenly heard the sound of the gunshots and fell prostrate. It seemed like an attack from the Viet Cong. One person was shot and injured, so we pulled him to the rear before radio contacting the company leader. He advised us to go into the villages, so we went in with our guns pointed.

Investigator: What was it like when you went into Phong Nhị?

Lieutenant Choi: There were only children, women, and the elderly. We went into their homes and told them all to get out. We sent them to the rear and walked through the entire village.

Investigator: Didn't you hear the sound of gunshots again?

Lieutenant Choi: Yes, we heard the sound of gunfire after we reached the end of the village. It was a loud ruckus that left me with feeling unsettled.

Investigator: What happened?

Lieutenant Choi: I’m not sure. Behind my platoon, there was the second platoon, and then the third platoon behind them, but we couldn’t tell what was going on behind us from where we were.

Lieutenant Choi closed his eyes and tried to recall the day. The vignettes of the Vietnamese people in the villages appeared against a black screen in his head. Short peasant people dressed in white shirts, short black pants and satgats. It was not different from the landscape of rural villages in Korea.

He remembered that he and his platoon members had yelled, "Lai Lai," waving frantically at the Vietnamese people. “Lai Lai” was the most widely used Vietnamese phrase among Korean soldiers. They thought it meant, "all of you, come out," but that wasn’t an accurate translation. "Lai Lai" was Chinese. Even though “Lai” also meant “come” in Vietnamese, the phrase sounded a bit awkward to the Vietnamese.

They had commanded the villagers to get out of their homes for a search, trying to figure out what kinds of people resided in the villages. They were in fact searching the houses for a young man--a likely suspect. Knowing the danger associated, young Vietnamese men fled in advance from areas where South Korean troops operated. That day was no exception. There were only the elderly, women and children left. The villagers were sent to the back by the 1st platoon to the 2nd platoon, who then sent them further back to the 3rd platoon until they were all gathered in one place.

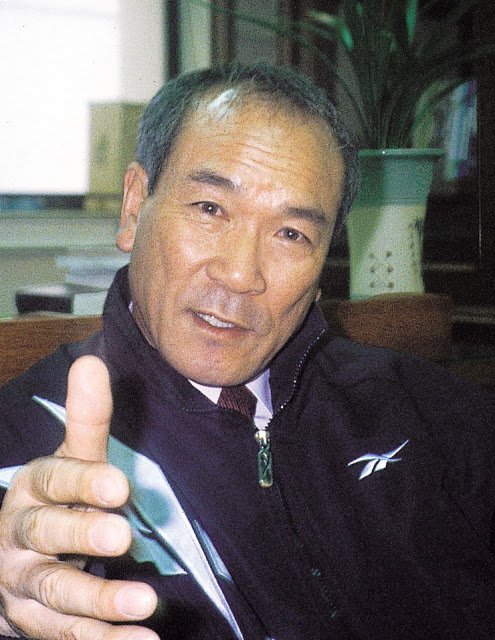

(From above to below) the 1st company, 1st platoon commander, Lieutenant Choi Young-un; 2nd platoon commander, Lieutenant Choi Sang-woo; and 3rd platoon commander, Kim Ki-dong, who entered Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất on February 12, 1968. Photograph taken in April of 2000.

Investigator: Didn't the villagers resist?

Lieutenant Choi: It was only the elderly, the women and the little ones. What power would they have to resist? We couldn't even find any weapons.

Investigator: So then why did you hear the gunshots?

Lieutenant Choi: We sent the villagers to the rear starting from the 1st platoon, so they must have all gathered in the back. Perhaps the villagers who were scared by the troops attempted to run away, leading to somebody being shot.

Investigator: Which platoon was it?

Lieutenant Choi: I didn't see it either. I only heard the sound.

The investigation continued into the afternoon after a short lunch break. The investigators inquired in detail about what Choi had seen and experienced on the day of the incident. Lieutenant Choi Young-un, however, wasn’t the only officer from the 1st company of the 2nd Brigade. Lieutenant Lee Sang-woo, leader of the 2nd platoon, and Lieutenant Kim Ki-dong, leader of the 3rd platoon (who was then serving at the Pohang Special Education Corps for Vietnam) were also being investigated by the Central Intelligence Agency.

Investigator: What did you do after you entered the village of Phong Nhị behind the 1st platoon?

Lieutenant Lee Sang-woo: I hardly saw any of the villagers. Our platoon members searched the houses, throwing grenades into their bomb shelters.

Investigator: Was there anyone in the bomb shelters?

Lieutenant Lee: Yes, a series of injured people came out after we threw the grenades, so we took them to the back. I remember there were about 70 to 80 such people. And then as we proceeded forward, we heard a gunshot from behind.

Lieutenant Lee Sang-woo of the 2nd platoon testified that the platoon members threw grenades into the underground bomb shelters.[2] It wasn’t yet clear which platoon was responsible for the full-scale slaughter, but it was evident that the some bloodshed of the residents was initiated by the 2nd platoon. The residents must have been frightened after hearing several hand grenades explode and seeing fellow villagers shedding blood. Deaths may have occurred in the process even. Without being able to communicate properly, the residents likely thought that the South Korean soldiers who were searching their homes, were out to hurt them. They must have been scared as they were taken out of their homes by the 1st and 2nd platoon members and sent to the rear toward the 3rd platoon.

Investigator: Do you see this photograph of the corpses? Have you ever seen it?

Lieutenant Kim Ki-dong: Yes, I did. I was scouting the number one national highway on the morning of February 13, 1968, the day after the incident, and I saw the residents laying down corpses on the road. This looks like a picture from that time.

Lieutenant Kim Ki-dong, the 3rd platoon leader, was wrong. The photograph was not taken the day after the incident. But how would he have known that in the afternoon of February 12, 1968, after the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd platoons of the 1st company left Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất, U.S. soldiers entered immediately after and took photographs of the corpses? Of course, Lieutenant Kim hadn’t intentionally lied; he was just mistaken. It was true that on the morning of February 13, 1968, the residents of Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất laid the corpses of the people who were killed the day before by the South Korean troops, near the number one national highway. At the time, the first company soldiers who were scouting the area witnessed the scene. The troops shivered at the sight of dead bodies with missing heads and limbs. Lieutenant Kim recalled that it was a day of intense tension, during which he kept looking around in fear that a bullet might fly toward him at any given minute. Perhaps the picture of the corpses was secondary, as the following question was what really penetrated the platoon leader.

Investigator: The 1st and 2nd platoon leaders said they sent the villagers back toward the 3rd platoon; what happened when they got to the 3rd platoon?

Lieutenant Kim: ......

Investigator: Did the 3rd platoon fire at the residents?

Lieutenant Kim: ......

There is no way to know what Lieutenant Kim, the 3rd platoon commander, said in response. Did he claim that the 3rd platoon members started shooting because, instead of going in the direction that the soldiers ordered, the villagers ran off on their own? Or had somebody in the 3rd platoon heard the news that somebody in the first platoon was shot and therefore instigated the rest of the platoon to attack the villagers? In fact, he could have just claimed that it wasn’t his platoon’s doing.

The testimonies of the 1st and 2nd platoon leaders as well as those of the 1st and 2nd platoon members were more or less consistent. They claimed that other than those villagers who were injured by the hand grenades, there was nobody who was shot by the platoon members.[3] On the day of the incident, the first company entered the village of Phong Nhị in indian file, the platoons lined up in numerical order. In addition to the commander and a messenger, the headquarters had two U.S. military radio soldiers for gunships and air support. The residents who were sent to the back by the 2nd platoon were unmistakably gathered in one place where the 3rd platoon was. An accidental firing here or there could have been possible without the platoon leader's permission or acquiescence. But if there were more than 70 people, how could the platoon leader have not known when so many were being shot to death? The 3rd platoon members were the most likely suspects within the company.[4]

”There is no way to know what Lieutenant Kim of the 3rd platoon testified in the Central Intelligence Agency's investigation room. However, one day in April of 2000, 31 years after Kim retired from the Marine Corps and became a civilian, he said, "I could hear the sound of gunshot and see the village burning before my eyes. I just remember passing by three or four dead bodies and wounded people holding their children in their arms." [5] Thirteen years later in October of 2013, he testified, "If anything, the platoon in front of us incited it; we had nothing to do with it. When you’re in a line of march, the first platoon alone is 100 meters long. The same goes for the 2nd platoon. We're following right behind them. How are we supposed to fire our guns with the entire company headquarters in front of us? And besides, a gun can be fired at anything--a dog, or even into the air.” [6]

At the Central Intelligence Agency in November of 1969, Lieutenant Choi, Lieutenant Lee, and Lieutenant Kim, each of whom was questioned in a different room, convened in front of the restroom. In addition to the three officers, there was captain Kim Seok-hyun, who was the company commander at the time of the incident. Kim returned to his home country immediately after the incident. Officers were usually deployed for one year. Kim, who came to Vietnam on November 20, 1967, had only served in Vietnam for three months and 13 days before returning home on March 2, 1968. There is no way to know what Captain Kim said in his testimony at the Central Intelligence Agency. In April of 2000, when I had a phone interview with him, he said that because they “are all spread out during combat, this could only be construed as individual action, for which no group could be held responsible. Your guess is as good as mine.” Soon after he returned from Vietnam, he emigrated to Brazil.[7]

Captain Kim Seok-hyun was not the only one who returned home in a hurry after the incident. Brigade General Kim Yeon-sang, the second brigade commander of the Marine Corps, also returned to South Korea less than six months after the incident. There is no explicit record that the two were returned as a consequence of their involvement in the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất incident. There is only speculation that such was the case.

Officers weren’t the only ones questioned by the Central Intelligence Agency. Staff sergeants, as well as sergeants who had already been discharged, were also summoned. The investigation ended before sunset. The Marine Corps headquarters in Huam-dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul, sent a small bus to transport about 10 former members of the 1st Company to and from the headquarters. It was time to disband. Choi suggested to Lee and Kim that they have dinner together since it’s been a while. Several sergeants joined them for dinner at a bustling restaurant in Myeong-dong. No one brought up the matter of February 12, 1968 as they repeatedly clinked their soju glasses.

Why had the Central Intelligence Agency suddenly called in the officers and soldiers of the Marine Corps 2nd Brigade, who entered the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất on February 12, 1968, and investigate them a year and nine months later? Lieutenant Choi could not forget the words of the investigator: "Mr. President wants to know the truth." It had been a special investigation ordered by the president. President Park Chung-hee was very curious about the truth behind the incident without any explanation of why.

[1] Reconstructed using the Central Intelligence Agency's investigation transcript of the platoon commanders' memories and testimonies .

[2]《Hankyoreh 21》Cover story "Civilian massacre investigated by the Central Intelligence Agency," dated May 4, 2000, page 21, Ko Kyung-tae and Hwang Sang-chul. Lee Sang-woo, a former 2nd lieutenant general, has retired from being a university professor in Busan. In the fall of 2013, we sent two interview request letters to the address we received from his university, but both were returned saying ‘recipient unknown’.

[3] Ryu Jin-sung, a former private of the 2nd company of the1st battalion of the Marine Corps 2nd Brigade, who met me in June and July of 2018, testified that when he was entering Phong Nhị with Lee Sang-woo, 2nd platoon leader on February 12, 1968, they witnessed a corporal indiscriminately killing a senior citizen with an M16 rifle.

[4] "I heard that it happened in the far back end of the company," Ryu Jin-sung said, referring to the possibility that it was the 3rd platoon that fired. Choi Young-un, a former 1st platoon commander, had already stated that the 3rd platoon is culpable.

[5]《Hankyoreh 21》, May 4, 2000, cover story titled "Civilian massacre investigated by the Central Intelligence Agency"

[6] I was able to get hold of Kim Ki-dong, former commander of the 3rd platoon, in October of 2013 and booked an interview at his home in Myeonmok-dong, Jungnang-gu. I visited at the appointed time, but no one was home. When I contacted him on his cell phone, he said he had completely forgotten, that he was at a Marine Corps gathering, and suggested that we reschedule. The next day he called and claimed that he will be moving to Daegu for the time being. In several subsequent phone calls, he denied that the 3rd platoon had anything to do with the incident of February 12, 1968. He made various excuses for not being able to meet in person to tell me more in detail about his participation in the Vietnam War.

[7] Kim Seok-hyun, a former company commander who was living in Sao Paulo in 2000, rejected a face-to-face interview request through Oh Jin-young, Hankyoreh 21’s Sao Paulo correspondent. As of January 2015, we have not been able to get a hold of him.

- Written by humank (Journalist; Seoul, Korea)

- Translated and revised as necessary by April Kim (Tokyo, Japan)

The numbers in parentheses indicate the respective ages of the people at the time in 1968.

Congratulations @humank! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPTo support your work, I also upvoted your post!

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!