22. The Currency War

Precursor to the Mỹ Lai Massacre: 1968 Phong Nhị, Phong Nhất_22: The Currency War

Click to read in korean( 전쟁의 뒤안 군표의 장난)

The weather was a mess.

It rained violently in October of 1968. Strong winds blew for an entire week. Central Vietnam was especially vulnerable to heavy rains, as its flooded roads turned into reservoirs. On the number one national highway, all one could see was a lofty telegraph pole that stood tall. There were people who pulled out small emergency boats from the ceiling of their homes and rowed away. Occasionally, a jeep would drive by, half drowned in water, yet its engine still persisting. It was the famous M151A1 jeep. This jeep, which was first developed in the United States in 1959 and incorporated into the Vietnam War in 1965, boasted perfect waterproofing. The clutch and other devices were specially designed to prevent water ingress. The muffler that releases exhaust gas was installed upwardly in the rear to prevent it from being submerged. The U.S. military called it the "Kennedy Jeep." The Kennedy Jeep showed great amphibious capacity in the Vietnamese landscape, which underwent explosive rainfall during the May-October rainy season. For this reason, it was even referred to as " the hero of the Vietnam War." The U.S. military also supplied the Kennedy Jeep to the South Korean military. The Marine Corps 1st battalion, 2nd Brigade was allocated two units. It was for the battalion commander and the battalion staff.

In October 21, 1968, Lieutenant Choi Young-un, the first personnel administration officer, watched the Kennedy Jeep passing to and fro from above. He was en route to an operational area on a U.S. military helicopter. Choi, after serving as the first platoon leader and deputy commander of the 1st company, became the personnel administrator of the first battalion whose duties were far from being combat-related. That day, his duty was collecting military currency certificates from company members located in areas that were difficult to access by land, even on a Kennedy jeep.

Time was running out. The only possible means of transportation were helicopters. The helicopter lowered its altitude as it reached the operational area of the jungle. All the surfaces were flooded, preventing them from landing. They lowered the altitude as much as possible without coming into contact with water. He opened the helicopter door. A company officer who had been waiting below waved. Lieutenant Choi Young-un also waved back. The officer threw a plastic bag from a close distance, and Choi caught it. The door closed, and the helicopter ascended again. Choi opened the plastic bag. There were military currency certificates of various values: five cents, ten cents, twenty-five cents and a dollar. The helicopter headed for another place, again to collect military currency certificates.

The article on the exchange of military currency certificates for the U.S. Army in Vietnam, published in the Kyunghyang Shinmun, October 21, 1968.

They were given twelve hours. At 7:00 a.m. on Oct. 21, the U.S. Army Command made an unexpected announcement that it would void all existing military currency certificates, advising that the old currency certificates be exchanged for new currency certificates within the next twelve hours (the front page of the Seoul-based Kyunghyang Shinmun, "Changing the U.S. Army's military currency certificate in Vietnam" Oct. 21, 1968). Immediately, orders were issued from the brigade headquarters to organize and collect the military currency certificates held by the soldiers and to go to the marine corps resort in Da Nang and exchange them for new ones. The soldiers were flabbergasted. How were they supposed to gather all the military currency certificates of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd squadrons within 12 hours amid the strong winds and heavy rain? Some of the company members were out on operations in the jungles. No one understood why they chose the monsoon season to make a big fuss about exchanging military currency certificates. What was so urgent? Yet no amount of grumbling would change their circumstance. Lieutenant Choi radio contacted each of the companies, ordering that the value of each individual’s currency certificates be calculated, collected, and passed on to him at the respective operational area of each company. A collection operation, perhaps more urgent than any military operation for combat, had commenced.

A military currency certificate is a special currency. In the event of war or military presence in a foreign country, it is issued by the government or military authorities to use to buy necessary goods. In the case of the Vietnam War, troops who had been dispatched at the request of the United States were given military currency certificates issued by U.S. military authorities. Military currency certificates looked completely different from the paper dollar bills that the U.S. Federal Reserve issued. South Korean soldiers in Vietnam received their military currency certificates once a month, just like their monthly salaries. Even while on search and reconnaissance missions in the jungle, the date of the military currency certificate payment was well observed. To be exact, it was a combat allowance, not a salary. An officer like Lieutenant Choi Young-un, for example, received $4.5 a day in combat allowance in Vietnam. The private first class received $1.35, their monthly allowance amounting to $135 and $40.5, respectively (the exchange rate was 282 korean won per U.S. dollar in 1968).

The salary given by the Ministry of National Defense was paid once for the entire year just before dispatch. In essence, officers or enlisted soldiers who were dispatched to Vietnam earned more than twice their original monthly salary. It was a tradeoff for putting their lives on the line.

The exchange of military currency certificates was a kind of currency reform. The moment the exchange of military currency certificates was announced, the existing currency certificates were rendered void. They would become but scraps of paper unless they were exchanged for new currency certificates within a set amount of time. The exchange of military currency certificates wasn’t necessarily such a serious issue for the soldiers. All they had to do was submit their currency certificates to the military authorities and exchange them for new ones. They didn’t even have that many currency certificates to begin with because at the time, the Korean government forced the troops to remit 80 percent of their combat allowance from the U.S. military to their homeland.

In South Korea, economic development was in full swing. The remitted military currency certificates boosted the country's foreign exchange reserves. The war allowance remitted in 1968 alone was $29.4 million (The total amount of money transferred between 1965 and 1967 was $195 million)[1]. Since the soldiers got to keep only 20 percent of their combat allowances in Vietnam, in reality, a lieutenant received only $27 a month and a private, only $8.1 a month, a negligible amount, especially for the latter.

Unlike in Da Nang, where there was a huge U.S. military presence, there was no U.S. PX in Hoi An, where the 2nd Brigade of the Korean Marine Corps was stationed. Soldiers used these military currency certificates to buy cigarettes, alcohol, coke and fruit in small shops in residential areas. The Vietnamese owners of these shops took the currency certificates and later exchanged it for U.S dollars or Vietnamese currency. The exchange rate for military currency certificates to actual U.S. dollars was originally 1:1, but in the underground markets, the rate was about 1.2:1. It was technically illegal for civilians to trade goods using military currency certificates. The reality, however, was different: military currency certificates held by U.S. and South Korean troops were widely accepted as real currency even outside the military bases.

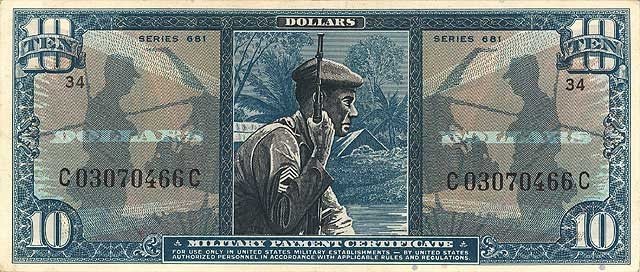

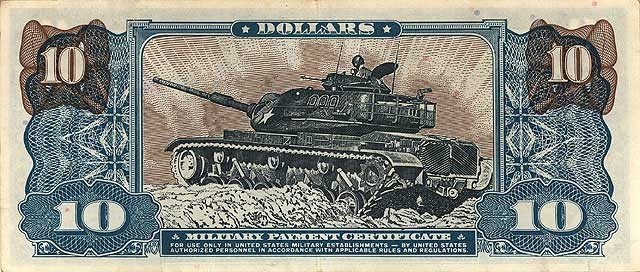

The U.S. military authorities declared at 7 a.m. on October 21, 1968, that the current currency certificates, the 661 series(above), will be exchanged for new currency certificates, the 681 series (below). Any currency certificate that wasn’t exchanged within the next 12 hours became meaningless scraps of paper.

The helicopter carrying Lieutenant Choi Young-un headed to Da Nang before sunset. Within 12 hours, all of the battalion's military currency certificates were collected. Personnel administrators from each battalion were supposed to assemble by evening at the Marine Corps resort in Da Nang. The brigade headquarters officials greeted the officers from each battalion. Choi submitted bundles of military currency certificates along with a report stating each individual’s amount from each company. A dispatched U.S. accounting officer reviewed the documents. Lieutenant Choi looked around keenly. He had with him another bundle of currency certificates, each worth $100. He debated whether or not to ask the U.S. military officer to exchange theses military currency certificates.

The $100 bundle was from two South Korean businessmen who came rushing to him at the break of dawn. They stated that they were referred to Choi, the battalion's personnel administrator, by their acquaintance who happened to be a senior government official. One of them introduced himself as the owner of the Arirang Restaurant. There were two Korean-run restaurants and a cabaret in Da Nang. Korean officers would stop by when they went on vacation or business trips to Da Nang. The alcohol, food and singing soothed the nostalgia of the South Korean military officers and soldiers. At the restaurant, they could enjoy kimchi stew and soju. At the cabaret, they danced to Lee Mi-ja's popular song, "Dongbaek lady.” Their main patrons were Koreans, mostly soldiers, who, of course, paid in military currency certificates.

As soon as the certificate exchange was announced, they fell into a panic as their hard-earned money was about to lose value entirely in twelve hours. They even offered to pay half the value of their bundle if Choi managed to get them exchanged for the new certificates. "I will try, but don’t get your hopes up," Choi said frankly. It was as expected. The U.S. accounting officer had a rough estimate of what the amount of the military currency certificates owned by Choi's battalion would be. When he saw the bills whose amount far exceeded the expected total for the battalion, he shook his head and flatly refused to exchange them. He knew that there could be no payment certificates of such amount.

They had already rehearsed this exchange of certificates a month ago, at which point the soldiers were completely unaware that it was a training drill. The officers and soldiers of each unit wrote down their certificate holdings just the same, but they didn’t actually have to submit the certificates. It was only after they sorted out each individual’s sum that they were notified that it was only practice—that it was more of a training. The plan was to secure data on combat allowances, the amount of money transferred from each unit and the average amount held per soldier, ahead of the actual exchange of certificates. They intentionally chose a day of heavy rain and therefore difficult mobility to execute the actual exchange. U.S. military PXs were shut down en masse, and a curfew was imposed on soldiers in the compounds. The surprise announcement was aimed at making it impossible for civilians to come up with countermeasures to the exchange.

The merchants of Hoi An and Da Nang were completely caught off guard. They were utterly devastated as their livelihood depended on selling goods to soldiers on military currency certificates. Any certificate that they hadn’t already exchanged into U.S. or Vietnamese currency was nothing but a useless piece of paper. Now with only 12 hours left in the heavy rain, it was nearly impossible to exchange it for the new certificates, unless one had a secret connection with a top U.S. military officer and cleverly maneuvered the relationship. The two South Korean businessmen clung to Choi as their last resort. The U.S. military authorities, who had heretofore been lax about military currency certificates’ being on the market, had purchased all sorts of items using huge amounts of make-believe money and suddenly wiped their slates clean. Just by changing the design of the currency alone, they managed to completely debilitate their opponents. Lieutenant Choi thought this a truly vicious act of thievery.

The U.S. military authorities stated that the urgent measures to replace military currency certificates was to prevent counterfeiting and black-market transactions. True to form, there was a flow of counterfeit military currency certificates and illegal distribution. But illegal distribution was possible only because the U.S. military abetted and acquiesced it. In addition, counterfeit currency was too meager to be used as an excuse for this abrupt change. The resulting U.S. gain and commensurate loss on part of the underground market was too great not to execute such a change.

Da Nang had a PX run by the U.S. Army Command in Vietnam. The PX, which surpassed the size of most department stores, embodied the material affluence of American society. It sold cigarettes, whiskey and daily necessities, as well as TVs, refrigerators, and even precious metals. It was common for South Korean military officers to buy diamond rings, which cost around $130 from the U.S. military's PX, in preparation for marriage upon returning to their homeland. Lieutenant Choi found it odd that diamond rings were being sold on the battlefield. He recalled the story of the British PX, which came up frequently among his fellow officers. During the Korean War, the British military set up a battalion-sized PX per company, quite accurately depicting the message that business was the essence of the war. Cashflow went unnoticed in the shadow cast by the weapon. The same went for military currency (On page 363 of the same book, the commentary titled, Commentary on page 363 of the same book. The novel, The Vietnam War and the Politics of the Empire (Lim Hong-bae), depicts the exchange of military currency certificates tickets as an important turn of events that hints at the demise of those who dream of making a fortune through currency exchange. [2]

[1] 『Statistical Analysis of the Vietnam War and the ROK Armed Forces』, Yongho Choi, Ministry of Defense Military Compilation Institute, 2007.

[2] "Listen, we can't come all the way here and be backstabbed by the yankees. They're changing the military currency certificates. I think our headquarters announced it today. The U.S. military has been prohibited from leaving premises since last week." (p. 303 Under the shadow of Arms, Hwang Seok-young, Changbi, 1992). The fictional character, Oh Hye-jung gains a kind of foreign exchange advantage by riding on the U.S. military authorities’manipulation of the value of military currency certificates.

- Written by humank (Journalist; Seoul, Korea)

- Translated and revised as necessary by April Kim (Tokyo, Japan)

The numbers in parentheses indicate the respective ages of the people at the time in 1968.

This series will be uploaded on Steemit biweekly.