Lies about the Romans, which we all believe

I don't think I exaggerate much when I say that most of the general public's knowledge about Rome and its time comes from film and television. Films such as "Ben Hur","Spartacus" or the most recent "Gladiator", as well as television series such as "Rome" or "Spartacus" have made the collective subconscious understand a series of concepts that, on many occasions, have nothing to do with what really happened. Even the productions that claim to be more faithful to history make mistakes that, to a large extent, are due to make a scene more effective. I don't blame them; after all, whoever goes to the cinema doesn't want to see a history documentary, but to entertain himself for a couple of hours.

Today we will try to dismantle some of the clichés that have been assumed about the Romans, but which are false. There are many, but I have chosen these for several reasons. The first reason is that they are deeply rooted in popular beliefs and almost all of them take them for granted. The second is that from time to time someone repeats them on social networks, helping to spread falsehoods by the force of repetition. The last reason is much more prosaic: because I wanted to write about these specific aspects, since their popularity is enormous and putting a point of sanity and historicity in deep-rooted (although false) beliefs has always been one of my weaknesses. Welcome to this harassment and demolish the myths about Rome.

Caligula named his horse consul

The Roman Emperor Caligula has passed into history as an example of a mad ruler. Of him are told delirious facts, such as that he maintained incestuous relations with his sisters and forced them to prostitution, or that he undertook a military campaign against the god Neptune, forcing his legions to stab the sea water and causing them to collect shells from the beach as spoils of war. But without a doubt, in the popular imagination there has remained an event that is put as an example of madness in a ruler: the appointment of his horse Incitatus for the position of consul. The consulate was the highest dignity of the Roman Republic, and although in the imperial era its authority was rather symbolic, it remained a high honor.

Incitatus was a Hispanic horse for whom Caligula felt a strange love. To begin with, he changed his primitive name from Porcellus (piggy) to the more feisty of Incitatus (impetuous). Such was the admiration for him that he made him build a marble stables with an ivory manger, where the horse ate oatmeal mixed with fine golden flakes. Shortly afterwards, he ordered him to build a villa where he was served by 18 servants. Caligula made him run in the races, where he only lost once, and that time he came face to face with his rival. It is said that the Emperor had him executed by emphasizing that the death must have been very painful. In addition, he ordered complete silence the night before the race (under penalty of death) so that Incitatus could rest properly. And finally, he appointed him consul.

The downside of all these stories is that they are drawn mainly from two historians, Suetonio and Dion Casio, who are much later. In addition, both were fervent Republicans, so they felt a special contempt for the imperial family. Relations between the Emperor and the Senate were not at all good (it is said that he once humiliated a group of senators who wanted an audience with him by having them run after his carriage), so senatorial sources tended to present Caligula as worse than he was. What does seem certain is that he mocked the senators by telling them that Incitatus would be a much better consul than any of them, and always presented him in public dressed in purple and adorned with jewels to mock the Senate. Did you really get to name him consul? Historians are divided on the issue, but there is a tendency to think that everything was an exaggeration. Probably, and according to classical sources, we will never know for sure.

The Romans clutched their testicles when they swore.

One of the most widespread clichés about the Romans is that they held their testicles tightly with the right hand when they took an oath, especially in court. Thus, they came to say that they compromised such a delicate part if they lied. This was repeatedly said to be the way in which it was emphasized that what was said next would be the truth and the whole truth. The question is concluded by saying that it follows from this peculiar form of swearing that the word "testifying" comes from "testicles" (some say it the other way around; that is,"testicles" comes from "testifying"). Every few minutes this story is posted on the Internet without missing whoever believes in it and then repeats it around.

It goes without saying that everything is false. It is true that both words come from "testis" (witnesses), but while testifying would be the result of the union of testis and facere (with what its meaning would be "to act as a witness"), testicle comes from adding to testis the suffix culus, used as diminutive (so its meaning would be "little witness"). But that's where all resemblance ends. They are two words that evolved in a different way, although in Spanish witness and testicle are pronounced in a similar way.

That said, how did the Romans swear? In reality there was no single way to swear, although it is known that they were made before any of their gods and the oath changed depending on the epoch or type of judgment. It is known that men used to swear by Hercules and women by Castor and Pollux. Likewise, in military trials he swore an oath on the sword. There are also testimonies that some women swore on their hair. In short, the oaths were very varied, but we must be clear that they were never made by squeezing the testicles.

Curiously, this hoax had a second version in the bosom of an institution that has reached our days: the Catholic Church. According to urban legend, when someone is elected Pope, a cardinal palpates his testicles to testify that he is a man and not a woman. Once the Pope's masculinity had been verified, the one in charge of carrying out this task (the palpathione) was to say "habet testicles" (he has testicles) or "habet duos t testicles et bene pendentes" (he has two testicles and they hang well). That said, the whole liturgy of the new Supreme Pontiff's coronation began. Of course, it's all fake.

The Romans vomited so they could keep eating.

One of the images that have drawn with more force when we imagine the world of the Romans is that of their bacchanal. If we ask someone to describe them to us as he thinks they were, he will talk to us about huge tables full of the most exotic dishes, of diners lying down eating and drinking without ceasing, and of insinuating dancers dancing lightweight clothes to the rhythm of the flutes. In addition, he is likely to tell us that, by virtue of the large amount of food, the Romans vomited so that they could continue to eat more. The bad news is that at least this last part is fake. The confusion comes from a writing by Cicero, who narrated that on one occasion Julius Caesar had been rid of an assassination attempt when, feeling sick at dinner, instead of going to the latrines (as his killers expected) he went to the vomitorium.

%20anton%20von%20werner.jpg)

This gave rise to the idea that the Romans had a special room where they vomited the excess food. However, vomiting was really something else: large corridors under the stands of theatres, amphitheaters and circuses to allow a large number of people to leave quickly. Even now we can still find the term in some countries referring to the corridors leading out of modern stadiums or some theatres. The confusion was helped by texts by Suetonio and Dion Casio, who told us that Emperor Claudius vomited the excess of supper before going to bed or that Vitelio (see my article "The Year of the Four Emperors") gave four feasts a day and between them vomited with the help of a bird's feather inserted into his throat. But these were isolated cases and not a common practice.

In conclusion, it is true that the wealthy classes gave (and did) lavish banquets. For example, Emperor Maximino is said to have eaten up to 16 kg in one meal. meat and 32 liters of wine, or that Emperor Albino was able to eat 500 figs, 10 melons, 100 peaches, 48 oysters and 2 kg for breakfast. of grapes. They are undoubtedly exaggerated figures, but they give an idea of how much some emperors ate. It is also said that the feasts that Luculo gave to his friends and guests were famous. But without a doubt, the banquet that Julius Caesar gave to celebrate his conquests in the East, considered the greatest in history, is the banquet that is said to have lasted several days, and that 260,000 people ate the food that was distributed on 22,000 tables.

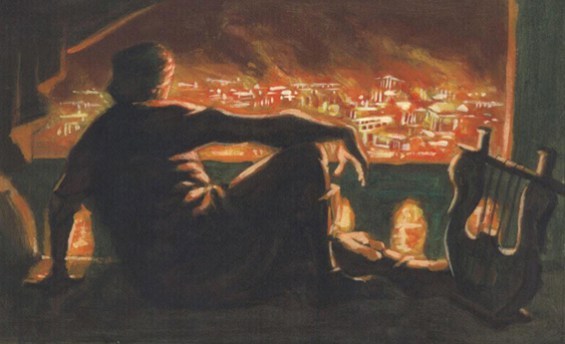

Nero touched the lyre while Rome burned

On July 19,64 Rome burned on all four sides. According to Tacitus, the fire lasted at least five days and four of the city's fourteen districts were burned to the ground. In addition, seven others were severely affected. Some of the city's most representative monuments were totally destroyed by the flames. Christians were blamed for this and subjected to intense persecution, although the popular imagination has rooted the idea that the real culprit was Nero. He is even depicted playing the lyre (other sources say the zither) as he watches the city burn. The fact that the emperor ordered the construction of his palace (called Domus Aurea, the golden house) and a large statue of him (called Colossus of Nero) on the land devastated by the flames contributed to this explanation. Curiously, in the place where this statue was, Vespasian ordered the erection of a large amphitheatre years later, which was named Colosseum in honor of the Colossus of Nero.

The truth is that today there is still no agreement among historians about the causes of the fire, although the general consensus is that it began accidentally in one of the food stores that swept around the Circus Maximus. However, Nero was accused almost immediately of being the perpetrator, although these accusations came from aristocratic and senatorial circles, which detested the emperor (instead, the plebs worshipped him, according to Tacitus). In addition, it appears that at the time of starting the fire Nero was in Anzio, 50 km away. of Rome, and that as soon as he heard the news he came to the city to take charge of the situation. Thus, he ordered his praetorian guard to collaborate in extinguishing the fire, opened the Mecenas and Lúculo gardens for those affected and ordered the distribution of food.

The popular belief that Nero watched the fire from his palace as he touched the lyre came again from later historians Suetonio and Dion Casio, who were very close to the senatorial nobility and therefore detested imperial power. However, it must be said that Nero wanted to shake off the suspicions that began to befall him in search of a scapegoat, and found him in a group that was beginning to be thriving in the city: the Christians. The later Christian historiography contributed to the depraved image of Nero and mythified the Christians who were martyred by the emperor, although this was not the first persecution they suffered (about eight years before Nero, the Christians were expelled from Rome by their predecessor Claudius). However, Tacitus, the only important contemporary historian of the events from which his version has come to us, completely discards Nero's involvement in the facts. But I fear that this belief is so deeply rooted that it will be impossible to eradicate it.

So, that was it.

See you later alligator. =)