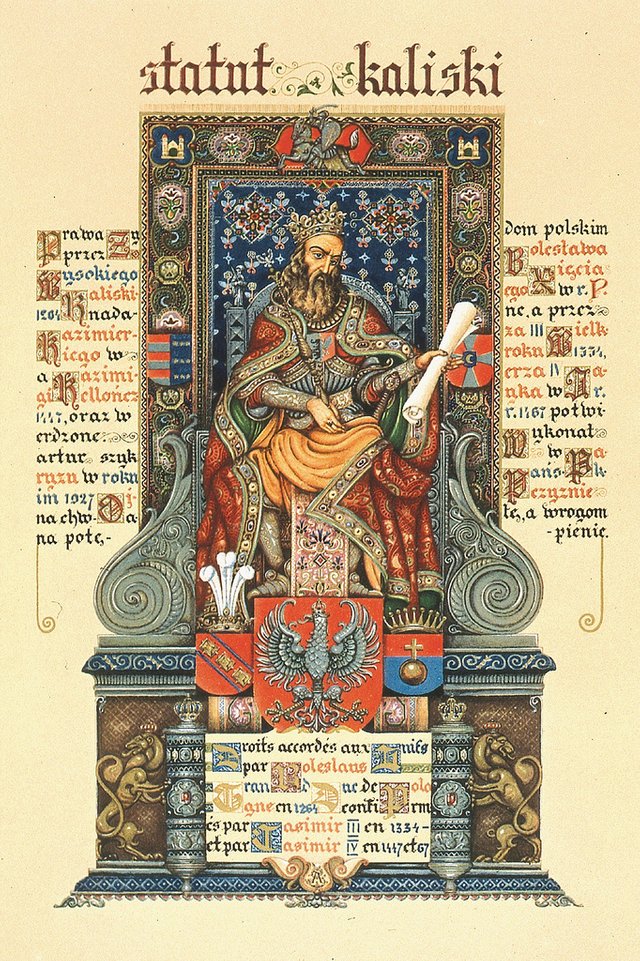

The Statute of Kalisz

During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, Christian rulers across Europe east and west persecuted and expelled Jews. While the papacy had denounced blood libel rumors, Christians from England to Crimea abused their Jewish neighbors, sometimes blaming them for the Black Death. In 1215, the Catholic Church decreed in the Fourth Lateran Council that Jews were to wear special clothing distinguishing them from Gentiles, and were to be segregated in ghettoes. In 1492, Queen Isabella the Catholic of Castile expelled the Jews from Spain. Seven hundred and fifty years ago today, the duke of Greater Poland, Boleslaus the Pious, issued one of the great exceptions to this pattern of persecution: the Statute of Kalisz.

The statute denounced blood libel charges, gave Jewish traders privileges, and made the presence of Jewish witnesses mandatory in the courts when Christians testified against Jews. The charter also proscribed the confiscation of property and “suitable punishment” for killing Jews. Most important, Jews were given their own pseudo-state within Poland in which they could use Yiddish as their official language. Jews were given their own courts in which they had exclusive jurisdiction over intra-Jewish affairs. Kalisz paved the way for a long tradition of tolerance that allowed Jewish life to blossom in Poland.

Later Polish leaders continued Boleslaus’s policies. Throughout the thirteenth century, Mongol invasions devastated Poland economically and demographically. To compensate for the losses in the labor force, King Casimir the Great invited Jews to settle in the country, and in 1334 he reaffirmed the Statute of Kalisz and introduced even more severe penalties for harming Jews.

As a consequence, for over six centuries Jewish civilization flourished in Poland. The Jews had their own Yiddish-language statutes, schools, synagogues, and even courts. Hasidism developed in Poland, while Cracow became a major center of Talmudic scholarship. Jews played a key role in Poland’s economy, making up a significant part of the merchant class and owning most village taverns. Poland was tolerant not only towards Jews, but other persecuted minorities as well. “Polonia mea est,” wrote Erasmus of Rotterdam, impressed by Polish tolerance. “Poland is mine.”

In the nineteenth century, as Poland disappeared from the map of Europe because of its partitions by its three stronger neighbors (Austria, Prussia, and Russia), Jewish and Gentile Poles fought for freedom in solidarity. Tadeusz Kosciuszko—best known to Americans as the father of the American cavalry and the military engineer whose plans were betrayed to the British by Benedict Arnold—also fought for Polish independence, and he formed the first Jewish military division since Biblical times, led by Berek Joselewicz. Adam Mickiewicz, Poland’s national poet, organized Jewish troops fighting Russia in the Crimean War. Meanwhile, such Jews as Cracow’s Rabbi Dow Ber Meisels bravely fought against Poland’s oppressors who sought to extinguish Polish culture by forcing Germanization or Russification on the people and the brutal oppression of the population’s constant restlessness (in 1863 a large anti-Russian uprising led to thousands of Poles’ being killed or deported to Siberia). Poland’s Romantic national poets—Mickiewicz, Juliusz S?owacki, and Cyprian Kamil Norwid—were philo-Semites who drew parallels between Polish suffering and Messianic Jewish theology.

Poland was no Shangri-la. Anti-Jewish violence by Poles occasionally erupted, while in the seventeenh century Ukrainians led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky rebelled against the Polish Crown, massacring countless Poles and Jews. During the Counterreformation, as Calvinism was growing across Poland, Rome sent the Jesuits there to re-Catholicize the population. Having a long history of anti-Semitism (as recently as 1946, men of Jewish ancestry could not become Jesuits), they harassed Jews. Yet pre-Partition Poland was still Paradisus Iudeaorum, a Jewish paradise.

In the twentieth century, the Polish tradition of philo-Semitism was confronted with growing nationalism. From when Poland regained its independence in 1918 until his death in 1935, philo-Semite Marshal Józef Pi?sudski ruled the country. Yet after his death, nationalists took power in Poland, infringing on the civil liberties of Jews and other ethnic and religious minorities. During World War II, hundreds of thousands of Poles risked their families’ lives by hiding Jews, but there were also those who betrayed or killed their Jewish neighbors. In 1968, Communist ruler W?adys?aw Gomu?ka (whose wife, ironically, was Jewish) expelled much of Poland’s Jewish population.

Despite these complications, the Polish philo-Semitic tradition prevailed. It inspired, among others, Jan Karski, the Polish government-in-exile’s courier who begged Churchill and Roosevelt to interfere to stop the Shoah. Karski’s parents raised him in the tradition of pious Catholicism, devotion to Marshal Pi?sudski and respect for the Jews.

Yet the most important exponent of the Polish tradition begun by the Statue of Kalisz was John Paul II. A pioneer of inter-religious dialogue, as his 1986 prayer with leaders of the world’s religions at Assisi shows, he had a love for the Jewish people, a sizeable minority in his hometown Wadowice. The first pope to visit a synagogue and to recognize Israel, John Paul’s oft-quoted statement that the Jews are Christians’ “elder brothers in the faith” came from Mickiewicz.

As we commemorate the Statute of Kalisz, it is worth noting that Poland’s ancient tradition of religious tolerance was not related to religious indifference. Instead, Poland was a bastion of Christendom, an Antemurale Christianitas. In 1683, Polish King John Sobieski saved Europe from a Muslim invasion at Vienna, writing to Pope Innocent XI: “Venimus, vidimus, Deus vincit (‘We came, we saw, God conquered’).” Today, many Polish Catholics want their country to be a bulwark against secularism, yet they engage in ecumenical dialogue. Devout yet tolerant, the sentiments of such Polish Catholics past and present can be similar to those of Polish King Sigismund II Augustus, a champion of the Counterreformation: “I am not the king of your consciences.”

The Polish tradition of religious tolerance, like Friar Bartholome de las Casas’s defense of Native Americans against forceful conversions or Pope St. Gregory the Great’s defense of European Jews against persecution, demonstrates how respect for the individual’s style of worship is a part of the Christian message.