ABRAHAM LINCOLN LIFE STORY

Jump to navigationJump to search

This article is about the 16th president of the United States. For other uses, see Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

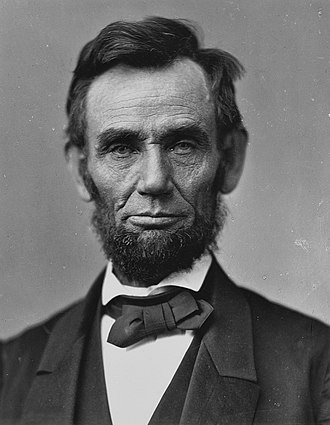

An iconic photograph of a bearded Abraham Lincoln showing his head and shoulders.

Lincoln in November 1863

16th President of the United States

In office

March 4, 1861 – April 15, 1865

Vice President

Hannibal Hamlin (1861–65)

Andrew Johnson (Mar–Apr 1865)

Preceded by James Buchanan

Succeeded by Andrew Johnson

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives

from Illinois's 7th district

In office

March 4, 1847 – March 3, 1849

Preceded by John Henry

Succeeded by Thomas L. Harris

Member of the

Illinois House of Representatives

from Sangamon County

In office

December 1, 1834 – December 4, 1842

Personal details

Born February 12, 1809

Sinking Spring Farm, Kentucky, U.S.

Died April 15, 1865 (aged 56)

Washington, D.C., U.S.

Cause of death Assassination

(gunshot wound to the head)

Resting place Lincoln Tomb

Political party

Whig (before 1854)

Republican (1854–1864)

National Union (1864–1865)

Height 6 ft 4 in (193 cm)[1]

Spouse(s) Mary Todd (m. 1842)

Children

RobertEdwardWillieTad

Mother Nancy Hanks

Father Thomas Lincoln

Signature Cursive signature in ink

Military service

Allegiance

United States

Illinois

Branch/service Illinois Militia

Years of service 1832

Rank

Captain[a]

Private[a]

Battles/wars American Indian Wars

Black Hawk War

Battle of Kellogg's Grove

Battle of Stillman's Run

Abraham Lincoln O-77 matte collodion print.jpg

This article is part of

a series about

Abraham Lincoln

Personal

Early life and careerFamilyHealth

Political

Political career, 1849–1861Lincoln–Douglas debatesCooper Union speechFarewell AddressViews on slaveryViews on religionElectoral history

President of the United States

Presidency

First term

1st inauguration Address

American Civil War The UnionEmancipation ProclamationTen percent planGettysburg Address13th Amendment

Second term

2nd inauguration Address

Reconstruction

Presidential elections

1860 Convention

1864 Convention

Assassination and legacy

AssassinationFuneral

Historical reputationMemorialsDepictions

Bibliography

Topical guide

vte

Abraham Lincoln (/ˈlɪŋkən/;[2] February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American statesman and lawyer who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation through the American Civil War, the country's greatest moral, constitutional, and political crisis. He succeeded in preserving the Union, abolishing slavery, bolstering the federal government, and modernizing the U.S. economy.

Lincoln was born into poverty in a log cabin and was raised on the frontier primarily in Indiana. He was self-educated and became a lawyer, Whig Party leader, Illinois state legislator, and U.S. Congressman from Illinois. In 1849, he returned to his law practice but became vexed by the opening of additional lands to slavery as a result of the Kansas–Nebraska Act. He reentered politics in 1854, becoming a leader in the new Republican Party, and he reached a national audience in the 1858 debates against Stephen Douglas. Lincoln ran for President in 1860, sweeping the North in victory. Pro-slavery elements in the South equated his success with the North's rejection of their right to practice slavery, and southern states began seceding from the union. To secure its independence, the new Confederate States fired on Fort Sumter, a U.S. fort in the South, and Lincoln called up forces to suppress the rebellion and restore the Union.

As the leader of moderate Republicans, Lincoln had to navigate a contentious array of factions with friends and opponents on both sides. War Democrats rallied a large faction of former opponents into his moderate camp, but they were countered by Radical Republicans, who demanded harsh treatment of the Southern traitors. Anti-war Democrats (called "Copperheads") despised him, and irreconcilable pro-Confederate elements plotted his assassination. Lincoln managed the factions by exploiting their mutual enmity, by carefully distributing political patronage, and by appealing to the U.S. people. His Gettysburg Address became a historic clarion call for nationalism, republicanism, equal rights, liberty, and democracy. Lincoln scrutinized the strategy and tactics in the war effort, including the selection of generals and the naval blockade of the South's trade. He suspended habeas corpus, and he averted British intervention by defusing the Trent Affair. He engineered the end to slavery with his Emancipation Proclamation and his order that the Army protect and recruit former slaves. He also encouraged border states to outlaw slavery, and promoted the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which outlawed slavery across the country.

Lincoln managed his own successful re-election campaign. He sought to heal the war-torn nation through reconciliation. On April 14, 1865, just days after the war's end at Appomattox, Lincoln was attending a play at Ford's Theatre with his wife Mary when he was assassinated by Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth. His marriage had produced four sons, two of whom preceded him in death, with severe emotional impact upon him and Mary. Lincoln is remembered as the martyr hero of the United States and he is consistently ranked as one of the greatest presidents in American history.

Contents

1 Family and childhood

1.1 Early life

1.2 Mother's death

1.3 First Employment

1.4 Education and move to Illinois

1.5 Marriage and children

2 Early career and militia service

3 Illinois state legislature (1834–1842)

4 U.S. House of Representatives (1847–1849)

4.1 Political views

5 Prairie lawyer

6 Republican politics (1854–1860)

6.1 Emergence as Republican leader

6.2 Lincoln–Douglas debates and Cooper Union speech

6.3 1860 presidential election

7 Presidency (1861–1865)

7.1 Secession and inauguration

7.2 Civil War

7.3 Re-election

7.4 Reconstruction

7.5 Native American policy

7.6 Other enactments

7.7 Judicial appointments

7.8 States admitted to the Union

7.9 Assassination

7.10 Funeral and burial

8 Religious and philosophical beliefs

9 Health

10 Legacy

10.1 Republican values

10.2 Reunification of the states

10.3 Historical reputation

10.4 Memory and memorials

11 See also

12 Explanatory notes

13 Citations

14 General sources

15 External links

15.1 Official

15.2 Organizations

15.3 Media coverage

15.4 Other

Family and childhood

Early life

Main article: Early life and career of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, the second child of Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks Lincoln, in a one-room log cabin on Sinking Spring Farm near Hodgenville, Kentucky.[3] He was a descendant of Samuel Lincoln, an Englishman who migrated from Hingham, Norfolk, to its namesake, Hingham, Massachusetts, in 1638. The family then migrated west, passing through New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Virginia.[4] Lincoln's paternal grandparents, his namesake Captain Abraham Lincoln and wife Bathsheba (née Herring), moved the family from Virginia to Jefferson County, Kentucky. The captain was killed in an Indian raid in 1786.[5] His children, including eight-year-old Thomas, Abraham's father, witnessed the attack.[6][b] Thomas then worked at odd jobs in Kentucky and Tennessee before the family settled in Hardin County, Kentucky in the early 1800s.[6]

The heritage of Lincoln's mother Nancy remains unclear, but it is widely assumed that she was the daughter of Lucy Hanks.[8] Thomas and Nancy married on June 12, 1806, in Washington County, and moved to Elizabethtown, Kentucky.[9] They had three children: Sarah, Abraham, and Thomas, who died an infant.[10]

Thomas Lincoln bought or leased farms in Kentucky before losing all but 200 acres (81 ha) of his land in court disputes over property titles.[11] In 1816, the family moved to Indiana where the land surveys and titles were more reliable.[12] Indiana was a "free" (non-slaveholding) territory, and they settled in an "unbroken forest"[13] in Hurricane Township, Perry County, Indiana.[14][c] In 1860, Lincoln noted that the family's move to Indiana was "partly on account of slavery", but mainly due to land title difficulties.[16]

The farm site where Lincoln grew up in Spencer County, Indiana

In Kentucky and Indiana, Thomas worked as a farmer, cabinetmaker, and carpenter.[17] At various times, he owned farms, livestock and town lots, paid taxes, sat on juries, appraised estates, and served on county patrols. Thomas and Nancy were members of a Separate Baptists church, which forbade alcohol, dancing, and slavery.[18]

Overcoming financial challenges, Thomas in 1827 obtained clear title to 80 acres (32 ha) in Indiana, an area which became the Little Pigeon Creek Community.[19]

Mother's death

On October 5, 1818, Nancy Lincoln succumbed to milk sickness, leaving 11-year-old Sarah in charge of a household including her father, 9-year-old Abraham, and Nancy's 19-year-old orphan cousin, Dennis Hanks.[20] Ten years later, on January 20, 1828, Sarah died while giving birth to a stillborn son, devastating Lincoln.[21]

On December 2, 1819, Thomas married Sarah Bush Johnston, a widow from Elizabethtown, Kentucky, with three children of her own.[22] Abraham became close to his stepmother, and called her "Mother".[23] Lincoln disliked the hard labor associated with farm life. His family even said he was lazy, for all his "reading, scribbling, writing, ciphering, writing Poetry, etc".[24] His stepmother acknowledged he did not enjoy "physical labor", but loved to read.[25]

First Employment

At seventeen, Abraham left the family home for a while to work on a ferry at the junction of Anderson and Ohio.

At nineteen, he lost his sister Sarah, who died giving birth to her first child. In April 1828, he signed a contract with James Gentry, a neighboring settler, under which he was to bring a boat of agricultural products to New Orleans. [26] The journey lasted three months, during which he travelled with one of Gentry's sons to Ohio then to Mississippi where they had to face strong currents and an attack from their cargo. Back in Indiana, Abraham gave his father the $25 this contract earned him. [27]

In March 1830, when Abraham was 21, Thomas Lincoln decided to move to the fertile lands of Illinois, on the edge of the Sangamon River. His son helped him clear his new land. The following winter was harsh and the family remained stranded for several months by snow and ice.

Education and move to Illinois

A statue of young Lincoln sitting on a stump, holding a book open on his lap

Young Lincoln by Charles Keck at Senn Park, Chicago

Lincoln was mostly self-educated, except for some schooling from itinerant teachers of less than 12 months aggregate.[28] He persisted as an avid reader and retained a lifelong interest in learning.[29] Family, neighbors, and schoolmates recalled that his reading included the King James Bible, Aesop's Fables, John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress, Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe, and The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin.[30]

As a teen, Lincoln took responsibility for chores, and customarily gave his father all earnings from work outside the home until he was 21.[31] Lincoln was tall, strong, and athletic, and became adept at using an ax.[32] He gained a reputation for strength and audacity after winning a wrestling match with the renowned leader of ruffians known as "the Clary's Grove Boys".[33]

In March 1830, fearing another milk sickness outbreak, several members of the extended Lincoln family, including Abraham, moved west to Illinois, a free state, and settled in Macon County.[34][d] Abraham then became increasingly distant from Thomas, in part due to his father's lack of education.[36] In 1831, as Thomas and other family prepared to move to a new homestead in Coles County, Illinois, Abraham struck out on his own.[37] He made his home in New Salem, Illinois for six years.[38] Lincoln and some friends took goods by flatboat to New Orleans, Louisiana, where he was first exposed to slavery.[39]

Marriage and children

Further information: Lincoln family, Health of Abraham Lincoln, and Sexuality of Abraham Lincoln

A seated Lincoln holding a book as his young son looks at it

1864 photo of President Lincoln with youngest son, Tad.

Black and white photo of Mary Todd Lincoln's shoulders and head

Mary Todd Lincoln, wife of Abraham Lincoln, in 1861

Lincoln's first romantic interest was Ann Rutledge, whom he met when he moved to New Salem. By 1835, they were in a relationship but not formally engaged.[40] She died on August 25, 1835, most likely of typhoid fever.[41] In the early 1830s, he met Mary Owens from Kentucky.[42]

Late in 1836, Lincoln agreed to a match with Owens if she returned to New Salem. Owens arrived that November and he courted her for a time; however, they both had second thoughts. On August 16, 1837, he wrote Owens a letter saying he would not blame her if she ended the relationship, and she never replied.[43]

In 1839, Lincoln met Mary Todd in Springfield, Illinois, and the following year they became engaged.[44] She was the daughter of Robert Smith Todd, a wealthy lawyer and businessman in Lexington, Kentucky.[45] A wedding set for January 1, 1841 was canceled at Lincoln's request, but they reconciled and married on November 4, 1842, in the Springfield mansion of Mary's sister.[46] While anxiously preparing for the nuptials, he was asked where he was going and replied, "To hell, I suppose."[47] In 1844, the couple bought a house in Springfield near his law office. Mary kept house with the help of a hired servant and a relative.[48]

Lincoln was an affectionate husband and father of four sons, though his work regularly kept him away from home. The oldest, Robert Todd Lincoln, was born in 1843 and was the only child to live to maturity. Edward Baker Lincoln (Eddie), born in 1846, died February 1, 1850, probably of tuberculosis. Lincoln's third son, "Willie" Lincoln was born on December 21, 1850, and died of a fever at the White House on February 20, 1862. The youngest, Thomas "Tad" Lincoln, was born on April 4, 1853, and survived his father but died of heart failure at age 18 on July 16, 1871.[49][e] Lincoln "was remarkably fond of children"[51] and the Lincolns were not considered to be strict with their own.[52] In fact, Lincoln's law partner William H. Herndon would grow irritated when Lincoln would bring his children to the law office. Their father, it seemed, was often too absorbed in his work to notice his children's behavior. Herndon recounted, "I have felt many and many a time that I wanted to wring their little necks, and yet out of respect for Lincoln I kept my mouth shut. Lincoln did not note what his children were doing or had done."[53]

The deaths of their sons, Eddie and Willie, had profound effects on both parents. Lincoln suffered from "melancholy", a condition now thought to be clinical depression.[54] Later in life, Mary struggled with the stresses of losing her husband and sons, and Robert committed her for a time to an asylum in 1875.[55]

Early career and militia service

Further information: Early life and career of Abraham Lincoln and Abraham Lincoln in the Black Hawk War

In 1832, Lincoln joined with a partner, Denton Offutt, in the purchase of a general store on credit in New Salem.[56] Although the economy was booming, the business struggled and Lincoln eventually sold his share. That March he entered politics, running for the Illinois General Assembly, advocating navigational improvements on the Sangamon River. He could draw crowds as a raconteur, but he lacked the requisite formal education, powerful friends, and money, and lost the election.[57]

Lincoln briefly interrupted his campaign to serve as a captain in the Illinois Militia during the Black Hawk War.[58] In his first campaign speech after returning, he observed a supporter in the crowd under attack, grabbed the assailant by his "neck and the seat of his trousers", and tossed him.[34] Lincoln finished eighth out of 13 candidates (the top four were elected), though he received 277 of the 300 votes cast in the New Salem precinct.[59]

Lincoln served as New Salem's postmaster and later as county surveyor, but continued his voracious reading, and decided to become a lawyer. He taught himself the law, with Blackstone's Commentaries, saying later of the effort, "I studied with nobody."[60]

Illinois state legislature (1834–1842)

Lincoln's home in Springfield, Illinois

Lincoln's second state house campaign in 1834, this time as a Whig, was a success over a powerful Whig opponent.[61] Then followed his four terms in the Illinois House of Representatives for Sangamon County.[62] He championed construction of the Illinois and Michigan Canal, and later was a Canal Commissioner.[63] He voted to expand suffrage beyond white landowners to all white males, but adopted a "free soil" stance opposing both slavery and abolition.[64] In 1837 he declared, "[The] Institution of slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy, but the promulgation of abolition doctrines tends rather to increase than abate its evils."[65] He echoed Henry Clay's support for the American Colonization Society which advocated a program of abolition in conjunction with settling freed slaves in Liberia.[66]

Admitted to the Illinois bar in 1836,[67] he moved to Springfield and began to practice law under John T. Stuart, Mary Todd's cousin.[68] Lincoln emerged as a formidable trial combatant during cross-examinations and closing arguments. He partnered several years with Stephen T. Logan, and in 1844 began his practice with William Herndon, "a studious young man".[69]

U.S. House of Representatives (1847–1849)

Middle aged clean shaven Lincoln from the hips up.

Lincoln in his late 30s as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives. Photo taken by one of Lincoln's law students around 1846.

True to his record, Lincoln professed to friends in 1861 to be "an old line Whig, a disciple of Henry Clay".[70] Their party favored economic modernization in banking, tariffs to fund internal improvements including railroads, and urbanization.[71]

In 1843, Lincoln sought the Whig nomination for Illinois' 7th district seat in the U.S. House of Representatives; he was defeated by John J. Hardin though he prevailed with the party in limiting Hardin to one term. Lincoln not only pulled off his strategy of gaining the nomination in 1846, but also won election. He was the only Whig in the Illinois delegation, but as dutiful as any, participated in almost all votes and made speeches that toed the party line.[72] He was assigned to the Committee on Post Office and Post Roads and the Committee on Expenditures in the War Department.[73] Lincoln teamed with Joshua R. Giddings on a bill to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia with compensation for the owners, enforcement to capture fugitive slaves, and a popular vote on the matter. He dropped the bill when it eluded Whig support.[74]

Political views

On foreign and military policy, Lincoln spoke against the Mexican–American War, which he imputed to President James K. Polk's desire for "military glory—that attractive rainbow, that rises in showers of blood".[75] He supported the Wilmot Proviso, a failed proposal to ban slavery in any U.S. territory won from Mexico.[76]

Lincoln emphasized his opposition to Polk by drafting and introducing his Spot Resolutions. The war had begun with a Mexican slaughter of American soldiers in territory disputed by Mexico, and Polk insisted that Mexican soldiers had "invaded our territory and shed the blood of our fellow-citizens on our soil".[77][verification needed] Lincoln demanded that Polk show Congress the exact spot on which blood had been shed and prove that the spot was on American soil.[78] The resolution was ignored in both Congress and the national papers, and it cost Lincoln political support in his district. One Illinois newspaper derisively nicknamed him "spotty Lincoln".[79] Lincoln later regretted some of his statements, especially his attack on presidential war-making powers.[80]

Lincoln had pledged in 1846 to serve only one term in the House. Realizing Clay was unlikely to win the presidency, he supported General Zachary Taylor for the Whig nomination in the 1848 presidential election.[81] Taylor won and Lincoln hoped in vain to be appointed Commissioner of the General Land Office.[82] The administration offered to appoint him secretary or governor of the Oregon Territory as consolation.[83] This distant territory was a Democratic stronghold, and acceptance of the post would have disrupted his legal and political career in Illinois, so he declined and resumed his law practice.[84]

Prairie lawyer

See also: List of cases involving Abraham Lincoln

Lincoln in 1857

In his Springfield practice Lincoln handled "every kind of business that could come before a prairie lawyer".[85] Twice a year he appeared for 10 consecutive weeks in county seats in the midstate county courts; this continued for 16 years.[86] Lincoln handled transportation cases in the midst of the nation's western expansion, particularly river barge conflicts under the many new railroad bridges. As a riverboat man, Lincoln initially favored those interests, but ultimately represented whoever hired him.[87] He later represented a bridge company against a riverboat company in a landmark case involving a canal boat that sank after hitting a bridge.[88] In 1849, he received a patent for a flotation device for the movement of boats in shallow water. The idea was never commercialized, but it made Lincoln the only president to hold a patent.[89]

Lincoln appeared before the Illinois Supreme Court in 175 cases; he was sole counsel in 51 cases, of which 31 were decided in his favor.[90] From 1853 to 1860, one of his largest clients was the Illinois Central Railroad.[91] His legal reputation gave rise to the nickname "Honest Abe".[92]

Lincoln argued in an 1858 criminal trial, defending William "Duff" Armstrong, who was on trial for the murder of James Preston Metzker.[93] The case is famous for Lincoln's use of a fact established by judicial notice to challenge the credibility of an eyewitness. After an opposing witness testified to seeing the crime in the moonlight, Lincoln produced a Farmers' Almanac showing the moon was at a low angle, drastically reducing visibility. Armstrong was acquitted.[93]

Leading up to his presidential campaign, Lincoln elevated his profile in an 1859 murder case, with his defense of Simeon Quinn "Peachy" Harrison who was a third cousin; Harrison was also the grandson of Lincoln's political opponent, Rev. Peter Cartwright.[94] Harrison was charged with the murder of Greek Crafton who, as he lay dying of his wounds, confessed to Cartwright that he had provoked Harrison.[95] Lincoln angrily protested the judge's initial decision to exclude Cartwright's testimony about the confession as inadmissible hearsay. Lincoln argued that the testimony involved a dying declaration and was not subject to the hearsay rule. Instead of holding Lincoln in contempt of court as expected, the judge, a Democrat, reversed his ruling and admitted the testimony into evidence, resulting in Harrison's acquittal.[93]

Republican politics (1854–1860)

Main article: Abraham Lincoln in politics, 1849–1861

Emergence as Republican leader

Further information: Slave states and free states and Abraham Lincoln and slavery

Lincoln in 1858, the year of his debates with Stephen Douglas over slavery.

The debate over the status of slavery in the territories failed to alleviate tensions between the slave-holding South and the free North, with the failure of the Compromise of 1850, a legislative package designed to address the issue.[96] In his 1852 eulogy for Clay, Lincoln highlighted the latter's support for gradual emancipation and opposition to "both extremes" on the slavery issue.[97] As the slavery debate in the Nebraska and Kansas territories became particularly acrimonious, Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas proposed popular sovereignty as a compromise; the measure would allow the electorate of each territory to decide the status of slavery. The legislation alarmed many Northerners, who sought to prevent the resulting spread of slavery, but Douglas's Kansas–Nebraska Act narrowly passed Congress in May 1854.[98]

Lincoln did not comment on the act until months later in his "Peoria Speech" in October 1854. Lincoln then declared his opposition to slavery which he repeated en route to the presidency.[99] He said the Kansas Act had a "declared indifference, but as I must think, a covert real zeal for the spread of slavery. I cannot but hate it. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world ..."[100] Lincoln's attacks on the Kansas–Nebraska Act marked his return to political life.[101]

Nationally, the Whigs were irreparably split by the Kansas–Nebraska Act and other efforts to compromise on the slavery issue. Reflecting on the demise of his party, Lincoln wrote in 1855, "I think I am a Whig, but others say there are no Whigs, and that I am an abolitionist...I do no more than oppose the extension of slavery."[102] The new Republican Party was formed as a northern party dedicated to antislavery, drawing from the antislavery wing of the Whig Party, and combining Free Soil, Liberty, and antislavery Democratic Party members,[103] Lincoln resisted early Republican entreaties, fearing that the new party would become a platform for extreme abolitionists.[104] Lincoln held out hope for rejuvenating the Whigs, though he lamented his party's growing closeness with the nativist Know Nothing movement.[105]

In 1854 Lincoln was elected to the Illinois legislature but declined to take his seat. The year's elections showed the strong opposition to the Kansas–Nebraska Act, and in the aftermath, Lincoln sought election to the United States Senate.[101] At that time, senators were elected by the state legislature.[106] After leading in the first six rounds of voting, he was unable to obtain a majority. Lincoln instructed his backers to vote for Lyman Trumbull. Trumbull was an antislavery Democrat, and had received few votes in the earlier ballots; his supporters, also antislavery Democrats, had vowed not to support any Whig. Lincoln's decision to withdraw enabled his Whig supporters and Trumbull's antislavery Democrats to combine and defeat the mainstream Democratic candidate, Joel Aldrich Matteson.[107]

1856 campaign

Violent political confrontations in Kansas continued, and opposition to the Kansas–Nebraska Act remained strong throughout the North. As the 1856 elections approached, Lincoln joined the Republicans and attended the Bloomington Convention, which formally established the Illinois Republican Party. The convention platform endorsed Congress's right to regulate slavery in the territories and backed the admission of Kansas as a free state. Lincoln gave the final speech of the convention supporting the party platform and called for the preservation of the Union.[108] At the June 1856 Republican National Convention, though Lincoln received support to run as vice president, John C. Frémont and William Dayton comprised the ticket, which Lincoln supported throughout Illinois. The Democrats nominated former Secretary of State James Buchanan and the Know-Nothings nominated former Whig President Millard Fillmore.[109] Buchanan prevailed, while Republican William Henry Bissell won election as Governor of Illinois, and Lincoln became a leading Republican in Illinois.[110][f]

Painting

A portrait of Dred Scott, petitioner in Dred Scott v. Sandford

Dred Scott v. Sandford

Dred Scott was a slave whose master took him from a slave state to a free territory under the Missouri Compromise. After Scott was returned to the slave state he petitioned a federal court for his freedom. His petition was denied in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857).[g] Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney in the decision wrote that blacks were not citizens and derived no rights from the Constitution. While many Democrats hoped that Dred Scott would end the dispute over slavery in the territories, the decision sparked further outrage in the North.[113] Lincoln denounced it as the product of a conspiracy of Democrats to support the Slave Power.[114] He argued the decision was at variance with the Declaration of Independence; he said that while the founding fathers did not believe all men equal in every respect, they believed all men were equal "in certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness".[115]

Lincoln–Douglas debates and Cooper Union speech

Further information: Lincoln–Douglas debates and Cooper Union speech

In 1858 Douglas was up for re-election in the U.S. Senate, and Lincoln hoped to defeat him. Many in the party felt that a former Whig should be nominated in 1858, and Lincoln's 1856 campaigning and support of Trumbull had earned him a favor.[116] Some eastern Republicans supported Douglas from his opposition to the Lecompton Constitution and admission of Kansas as a slave state.[117] Many Illinois Republicans resented this eastern interference. For the first time, Illinois Republicans held a convention to agree upon a Senate candidate, and Lincoln won the nomination with little opposition.[118]

Abraham Lincoln (1860) by Mathew Brady, taken the day of the Cooper Union speech.

Accepting the nomination, Lincoln delivered his House Divided Speech, with the biblical reference Mark 3:25, "A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other."[119] The speech created a stark image of the danger of disunion.[120] The stage was then set for the election of the Illinois legislature which would, in turn, select Lincoln or Douglas.[121] When informed of Lincoln's nomination, Douglas stated, "[Lincoln] is the strong man of the party ... and if I beat him, my victory will be hardly won."[122]

The Senate campaign featured seven debates between the two. These were the most famous political debates in American history; they had an atmosphere akin to a prizefight and drew crowds in the thousands.[123] The principals stood in stark contrast both physically and politically. Lincoln warned that Douglas’ "Slave Power" was threatening the values of republicanism, and accused Douglas of distorting the Founding Fathers' premise that all men are created equal. Douglas emphasized his Freeport Doctrine, that local settlers were free to choose whether to allow slavery, and accused Lincoln of having joined the abolitionists.[124] Lincoln's argument assumed a moral tone, as he claimed Douglas represented a conspiracy to promote slavery. Douglas's argument was more legal, claiming that Lincoln was defying the authority of the U.S. Supreme Court in the Dred Scott decision.[125]

Though the Republican legislative candidates won more popular votes, the Democrats won more seats, and the legislature re-elected Douglas. Lincoln's articulation of the issues gave him a national political presence.[126] In May 1859, Lincoln purchased the Illinois Staats-Anzeiger, a German-language newspaper that was consistently supportive; most of the state's 130,000 German Americans voted Democratic but the German-language paper mobilized Republican support.[127] In the aftermath of the 1858 election, newspapers frequently mentioned Lincoln as a potential Republican presidential candidate, rivaled by William H. Seward, Salmon P. Chase, Edward Bates, and Simon Cameron. While Lincoln was popular in the Midwest, he lacked support in the Northeast, and was unsure whether to seek the office.[128] In January 1860, Lincoln told a group of political allies that he would accept the nomination if offered, and in the following months several local papers endorsed his candidacy.[129]

On February 27, 1860, powerful New York Republicans invited Lincoln to give a speech at Cooper Union, in which he argued that the Founding Fathers had little use for popular sovereignty and had repeatedly sought to restrict slavery. He insisted that morality required opposition to slavery, and rejected any "groping for some middle ground between the right and the wrong".[130] Many in the audience thought he appeared awkward and even ugly.[131] But Lincoln demonstrated intellectual leadership that brought him into contention. Journalist Noah Brooks reported, "No man ever before made such an impression on his first appeal to a New York audience."[132]

Historian David Herbert Donald described the speech as a "superb political move for an unannounced candidate, to appear in one rival's (Seward) own state at an event sponsored by the second rival's (Chase) loyalists, while not mentioning either by name during its delivery".[133] In response to an inquiry about his ambitions, Lincoln said, "The taste is in my mouth a little."[134]

1860 presidential election

Main article: 1860 United States presidential election

A Timothy Cole wood engraving taken from a May 20, 1860, ambrotype of Lincoln, two days following his nomination for president

On May 9–10, 1860, the Illinois Republican State Convention was held in Decatur.[135] Lincoln's followers organized a campaign team led by David Davis, Norman Judd, Leonard Swett, and Jesse DuBois, and Lincoln received his first endorsement.[136] Exploiting his embellished frontier legend (clearing land and splitting fence rails), Lincoln's supporters adopted the label of "The Rail Candidate".[137] In 1860, Lincoln described himself: "I am in height, six feet, four inches, nearly; lean in flesh, weighing, on an average, one hundred and eighty pounds; dark complexion, with coarse black hair, and gray eyes."[138] Michael Martinez wrote about the effective imaging of Lincoln by his campaign. At times he was presented as the plain-talking "Rail Splitter" and at other times he was "Honest Abe", unpolished but trustworthy.[139]

On May 18, at the Republican National Convention in Chicago, Lincoln won the nomination on the third ballot, beating candidates such as Seward and Chase. A former Democrat, Hannibal Hamlin of Maine, was nominated for vice president to balance the ticket. Lincoln's success depended on his campaign team, his reputation as a moderate on the slavery issue, and his strong support for internal improvements and the tariff.[140] Pennsylvania put him over the top, led by the state's iron interests who were reassured by his tariff support.[141] Lincoln's managers had focused on this delegation while honoring Lincoln's dictate to "Make no contracts that will bind me".[142]

As the Slave Power tightened its grip on the national government, most Republicans agreed with Lincoln that the North was the aggrieved party. Throughout the 1850s, Lincoln had doubted the prospects of civil war, and his supporters rejected claims that his election would incite secession.[143] When Douglas was selected as the candidate of the Northern Democrats, delegates from eleven slave states walked out of the Democratic convention; they opposed Douglas's position on popular sovereignty, and selected incumbent Vice President John C. Breckinridge as their candidate.[144] A group of former Whigs and Know Nothings formed the Constitutional Union Party and nominated John Bell of Tennessee. Lincoln and Douglas competed for votes in the North, while Bell and Breckinridge primarily found support in the South.[116]

Lincoln being carried by two men on a long board.

The Rail Candidate—Lincoln's 1860 platform, portrayed as being held up by a slave and his party

Map of the U.S. showing Lincoln winning the North-east and West, Breckinridge winning the South, Douglas winning Missouri, and Bell winning Virginia, West Virginia, and Kentucky.

In 1860, northern and western electoral votes (shown in red) put Lincoln into the White House.

Prior to the Republican convention, the Lincoln campaign began cultivating a nationwide youth organization, the Wide Awakes, which it used to generate popular support throughout the country to spearhead voter registration drives, thinking that new voters and young voters tended to embrace new parties.[145] People of the Northern states knew the Southern states would vote against Lincoln and rallied supporters for Lincoln.[146]

As Douglas and the other candidates campaigned, Lincoln gave no speeches, relying on the enthusiasm of the Republican Party. The party did the leg work that produced majorities across the North, and produced an abundance of campaign posters, leaflets, and newspaper editorials. Republican speakers focused first on the party platform, and second on Lincoln's life story, emphasizing his childhood poverty. The goal was to demonstrate the power of "free labor", which allowed a common farm boy to work his way to the top by his own efforts.[147] The Republican Party's production of campaign literature dwarfed the combined opposition; a Chicago Tribune writer produced a pamphlet that detailed Lincoln's life, and sold 100,000–200,000 copies.[148] Though he did not give public appearances, many sought to visit him and write him. In the runup to the election he took an office in the Illinois state capitol to deal with the influx of attention. He also hired John George Nicolay as his personal secretary, whom would remain in that role during the presidency.[149]

On November 6, 1860, Lincoln was elected the 16th president. He was the first Republican president and his victory was entirely due to his support in the North and West. No ballots were cast for him in 10 of the 15 Southern slave states, and he won only two of 996 counties in all the Southern states, an omen of the impending Civil War.[150][151] Lincoln received 1,866,452 votes, or 39.8% of the total in a four-way race, carrying the free Northern states, as well as California and Oregon.[152] His victory in the electoral college was decisive: Lincoln had 180 votes to 123 for his opponents.[153]

Presidency (1861–1865)

Main article: Presidency of Abraham Lincoln

Secession and inauguration

Further information: Secession winter and Baltimore Plot

Headlines on the day of Lincoln's inauguration portended hostilities with the Confederacy, Fort Sumter being attacked less than six weeks later.[154]

The South was outraged by Lincoln's election, and in response secessionists implemented plans to leave the Union before he took office in March 1861.[155] On December 20, 1860, South Carolina took the lead by adopting an ordinance of secession; by February 1, 1861, Florida, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas followed.[156] Six of these states declared themselves to be a sovereign nation, the Confederate States of America, and adopted a constitution.[157] The upper South and border states (Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri, and Arkansas) initially rejected the secessionist appeal.[158] President Buchanan and President-elect Lincoln refused to recognize the Confederacy, declaring secession illegal.[159] The Confederacy selected Jefferson Davis as its provisional president on February 9, 1861.[160]

Attempts at compromise followed but Lincoln and the Republicans rejected the proposed Crittenden Compromise as contrary to the Party's platform of free-soil in the territories.[161] Lincoln said, "I will suffer death before I consent ... to any concession or compromise which looks like buying the privilege to take possession of this government to which we have a constitutional right."[162]

Lincoln tacitly supported the Corwin Amendment to the Constitution, which passed Congress and was awaiting ratification by the states when Lincoln took office. That doomed amendment would have protected slavery in states where it already existed.[163] A few weeks before the war, Lincoln sent a letter to every governor informing them Congress had passed a joint resolution to amend the Constitution.[164]

A large crowd in front of a large building with many pillars.

March 1861 inaugural at the Capitol building. The dome above the rotunda was still under construction.

En route to his inauguration, Lincoln addressed crowds and legislatures across the North.[165] He gave a particularly emotional farewell address upon leaving Springfield; he would never again return to Springfield alive.[166][167] The president-elect evaded suspected assassins in Baltimore. On February 23, 1861, he arrived in disguise in Washington, D.C., which was placed under substantial military guard.[168] Lincoln directed his inaugural address to the South, proclaiming once again that he had no inclination to abolish slavery in the Southern states:

Apprehension seems to exist among the people of the Southern States that by the accession of a Republican Administration their property and their peace and personal security are to be endangered. There has never been any reasonable cause for such apprehension. Indeed, the most ample evidence to the contrary has all the while existed and been open to their inspection. It is found in nearly all the published speeches of him who now addresses you. I do but quote from one of those speeches when I declare that "I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so."

— First inaugural address, 4 March 1861[169]

Lincoln cited his plans for banning the expansion of slavery as the key source of conflict between North and South, stating "One section of our country believes slavery is right and ought to be extended, while the other believes it is wrong and ought not to be extended. This is the only substantial dispute." The president ended his address with an appeal to the people of the South: "We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies ... The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature."[170] The failure of the Peace Conference of 1861 signaled that legislative compromise was impossible. By March 1861, no leaders of the insurrection had proposed rejoining the Union on any terms. Meanwhile, Lincoln and the Republican leadership agreed that the dismantling of the Union could not be tolerated.[171] In his second inaugural address, Lincoln looked back on the situation at the time and said: "Both parties deprecated war, but one of them would make war rather than let the Nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish, and the war came.