$100 Billion Unrealized Revenue in Video Games

Why can't I buy a t-shirt from a video game?

In-Game merchandising could be the revenue model which start-up and indie game companies need to get over the hump as well as a tremendous tool in providing for massive profits for established game development companies.

But it isn’t, and I want to know why. After reading this article, please let me know your thoughts on why this monetization process isn't exploited by the video game industry - I need to know.

George Lucas has a few dollars in his account. Mainly from his success with Star Wars. But it wasn’t the movie, directly, which made Mr. Lucas a billionaire. It was merchandising.

In 1973, George Lucas had just finished directing the cult classic, “American Graffiti.” Set in 1962 and starring Richard Dreyfuss and Ronny Howard, the high-school comedy remains one of the most profitable movies of all time. Made on a budget of $750,000, it has earned over $200 million in revenue. The success of that movie provided Lucas with the leverage and credibility he needed to pitch the idea of a Sci-Fi western called “Star Wars.” In the 70’s nobody in Hollywood took sci-fi movies seriously. The genre had seen too many flops and the studios had collectively lost millions. Every studio Lucas pitched the idea to turned him down, until he spoke with Alan Ladd Jr. at 20th Century Fox. Fox was skeptical, but green-lighted the project. When Lucas said he would take a $500,000 cut on his directing fees in return for keeping the licensing and merchandising rights for himself, the studio jumped. Since the Fox anticipated the movie would bomb anyway, a half-million dollars in hand felt like a better investment than securing merchandising rights to something they assumed would be worthless. Fox's shortsightedness caused them to trade a billions for a half million.

Star Wars “A New Hope” was released on May 25, 1977 in 35 theaters. Immediately, it became part of our cultural fabric and shattered all expectations with a gross of $775.4 million worldwide, changing Hollywood forever. By 1978, more than 40 million Star Wars figures were sold for gross sales of more than $100 million. Lucas successfully turned those rights into a billion-dollar business, teaming with Kenner to launch a line of action figures around the original trilogy that proved so popular the company was literally selling kids “I.O.U.”s for Christmas sets. It also became the first IP to partner with LEGO for branded sets (a market that, in itself, has become a billion-dollar business). You can find Star Wars on just about anything now, and that’s the point. Over the past four decades, the franchise has grown to be one of the biggest merchandising forces in the world, accounting for well over $25 billion in sales to date.

Lucas was not only a visionary with his epic space western, but he was also a visionary in the way he saw the monetization of the cult around movies. He knew the movie would live in the real world and the tangible items that brought the movie into the home was the key in his vision. With full rights to himself, he created partnerships and manufactured action figures, toy light-sabers, the LEGO sets, the T-shirts, bed sheets, play-sets the X-Wing models, the tie-in books, the Yoda Halloween costumes, the Chewbacca pillows, the remote controlled R2D2s, and everything in between — stuff he could sell far beyond the run of the movie in theaters. Keep in mind, in 1977 no one had DVDs or VCRs much less Netflix or Amazon Prime Video – once the movie was out of the theaters, it was out of mind. Lucas knew he was creating a huge, fantastic world of science fiction, and that if people fell in love with the movies, they’d want to live in that world. And they did.

The rights were so valuable that they were a key piece of the negotiations during Disney’s purchase of Lucasfilm Ltd and the Star Wars franchise from Lucas. Lucas told Bob Iger he was considering retirement and planned to sell the company, as well as the Star Wars franchise. On October 30, 2012, Disney announced a deal to acquire Lucasfilm for $4.05 billion, with approximately half in cash and half in shares of Disney stock. Disney wanted to make a new trilogy and spin-off films, but the company needed to control all the other merchandise they’d be producing around it. It’s why the studio coughed up that mind-blowing $4 billion for the franchise. After the purchase, Disney rolled out over 100 new Star Wars toys and revitalized a cultural phenomenon, with a huge bottom line. Toy sales between the purchase and the end of that year reached over $2 billion in retail sales; with Disney's estimated royalty rate of 15 percent, Mickey can afford better cheese.

So why isn’t this happening in the Video Game Industry? Why can’t I even buy a T-Shirt in my favorite video game?

Video game players are the most passionate and engaged fans in the world and game developers capitalize on this by monetizing their games through digital products. Digital in-app Purchases (IAPs) are valued at $37 Billion. Industry leaders such as Supercell are pulling in over $2.4 billion in revenue through in-game digital purchases alone. But the industry is missing out on providing their fan base a tangible product by not selling the cult of the game to the real-world.

In 2015, the global video games market was worth approximately $71 billion. As we move closer to 2020, its value is expected to exceed $90 billion. While Lucas saw the value of merchandising opportunities in the 1970’s, the video game industry still relies on three basic monetization models to make those profits:

- Players pay for games

- In-game advertising to generate revenue

- Players spending money on micro-transactions

But I still can’t buy my T-Shirt in-game…

Each of those three monetization models can be implemented individually; however, in many cases, gaming companies choose to combine at least two of the three models to boost revenue. The combined models appear mostly in free-to-play (F2P) games, where players are encouraged to pay for enhancements, such as additional lives, currency, personalized avatars, skins, an ad-free experience, or unrestricted playing time. Those playing for free may face in-game advertisements, timers, a lack of customization options, or other hindrances. So much more is possible without penalizing the player… but no one is taking advantage of it.

While a $37 Billion industry of IAPs survives on $1.00 to $5.00 digital items, the boat is empty when it comes to the selling of the $20 to $100 items to fans. Sure, companies such as Rovio generated more than 40% of it’s $200 million revenue through the licensing of official Angry Birds merchandise, but I can’t buy my commemorative T-Shirt for my in-game achievement from in the game in the same way I can buy upgrades and in-game virtual items.

Compounding this frustration, the video game industry isn’t new to providing a physical product from an in-game experience. I’m old…maybe you are too and can remember the Atari 2600. Back then, Activision would send out achievement badges when a player reached a high score or a specific level in some games. The process was tedious as players had to take a picture of the TV screen and mail the photo to an address listed in the papers that came with the game… but they did it.

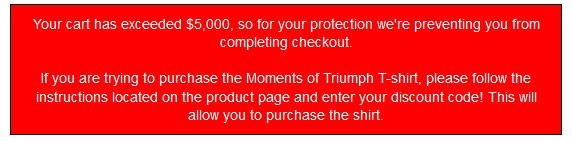

More recently Bungie used merchandising to generate buzz around the release of a new Destiny DLC. A player could go to the Bungie online store where the Destiny shirt was priced at $777,000. Obviously, no one could actually purchase the shirt, but playing the game and unlocking a Guardians Achievement would give the players a promo code which gave them a $776,975 discount on the shirt.

These examples, which span decades, show the continued interest of players for branded merchandise while providing a tangible part of a game in the real world. But the process is fractured. It’s inefficient for a player to look for or even know about an online store selling officially licensed merchandise for a game. However, if that player is shown the merchandise and provided a method of purchasing the items while in the game, the sale success is exponentially higher. The closer the point of purchase is to the point of engagement, the higher the likelihood of a sale.

In our world today, drop shipping and print on demand services allows for low inventory and overhead while maintaining a rapid supply chain of tangible products to players. Game studios have access everywhere to services for creating and shipping shirts, toys, figurines, collectibles – but the opportunity is missing.

Why?

Is this a tech problem? Is it a payment processing problem? Is it an international sales/tax collection problem? Is it a lack of vision problem? Is it that game development studios are excellent at building games, but the framework for the credit card vaults, tokenization, virual device trading, and the standardization across games is out of their wheelhouse? How did Lucas, in the 1970’s see the value of this opportunity, but the video game industry who has an audience of 1.4 billion active players not have a process where the engaged player who just slayed the Orc can purchase a T-Shirt from the game that has their achievement printed on it? Why can’t a player who customizes his character with upgraded skins and abilities purchase a 3D printed figurine of that character while he’s playing the game?

I need to understand.