Now gode

In the previous chapter of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, HCE sought asylum from his assailant. In the dreamworld of the novel his hiding place underwent several transformations: it was in turn an English country garden on the southeast bluffs of the stranger stepshore (ie Britain), his tavern in Chapelizod, a conservatory behind famine-built walls, a telephone booth, and finally a prison cell. At one point it also metamorphosed into a coffin:

The coffin, a triumph of the illusionist’s art, at first blench naturally taken for a handharp ... had been removed from the hardware premises of Oetzmann and Nephew, a noted house of the gonemost west which in the natural course of all things continues to supply funeral requisites of every needed description. ―RFW 053.24–29

In Finnegans Wake, HCE’s coffin is another example of the square-shaped siglum F, which represents containers of HCE―literal as well as figurative. As we saw in an earlier article, ALP’s Letter is also included in this siglum. As the Letter is about HCE, it contains him. On more than one occasion, Joyce uses this siglum to modulate from the Letter to the coffin or vice versa. One example of this occurred in the first chapter of the book, when Mutt & Jute’s dialogue about HCE’s burial mound was followed without a break by a discussion about a piece of writing (this claybook). In Chapter I.3 the paragraph about the coffin from which we have just quoted was preceded by a paragraph about a postman delivering the Letter (a huge chain envelope, or h ... c ... e). Now, for the third time, Joyce passes from one of these versions of F to the other: the first paragraph of this chapter included an unmistakeable allusion to the Letter and its siglum (sigilposted what in our brievingbust).

First-Draft Version

As usual, a good place to begin our analysis is with the first draft of this passage, as recorded by David Hayman:

The coffin was to come in handy later & in this way. A number of public bodies presented him a grave which nobody had been able to dig much less to occupy, it being all rock. This he blasted and then lined the result with bricks & mortar, encouraging the public bodies to present him over & above that with a stone slab. ―Hayman 75

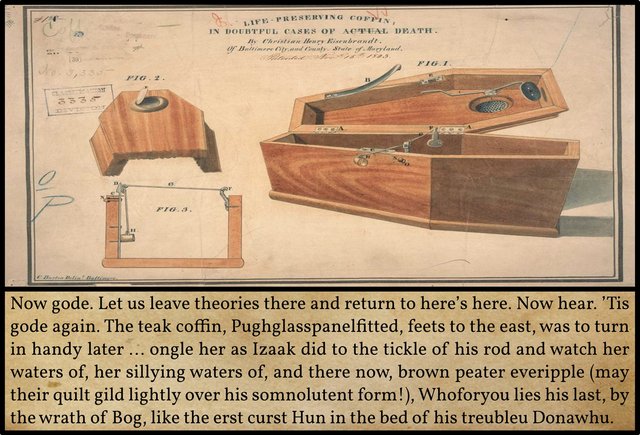

Recall that the description of the coffin in the preceding chapter included the fact that it was mistaken for a handharp. Now we are told that it was to come in handy later. (Note: in the first edition of Finnegans Wake the word handy was omitted.) Elsewhere I have suggested that Joyce’s zinzin motif (which is always associated with HCE’s coffin or burial mound) and comparisons of coffins with musical instruments may be allusions to safety coffins. A safety coffin is a coffin fitted with a bell or similar contrivance that enables the interred person to alert the world of the living that they have inadvertently been buried alive.

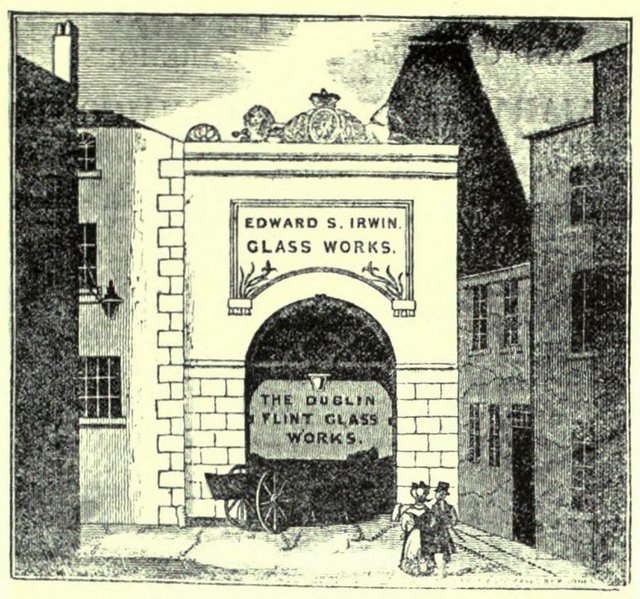

Another type of safety coffin has a glass panel through which the deceased may be monitored. If he is still alive, his breath will cloud the glass―though this only works if the coffin is placed in an accessible vault. Note that HCE’s coffin is Pughglasspanelfitted. Pugh Glassworks was a Dublin firm of glass manufacturers with premises on Potter’s Alley, off Marlborough Street. They were active between 1863 and about 1890.

HCE being an avatar of Tim Finnegan, the Irish navvy who helped build New York, it is hardly surprising that he has the skills of a master builder necessary to construct his own monumental tomb. As it is also a giant’s grave, who better to build it than the giant Finn MacCool? As we shall see, this paragraph contains an explicit allusion to Finn as a giant.

Dutch

The opening pages of this chapter are replete with Dutch words and expressions. In the previous article I suggested that this was because HCE is―in British naval slang―in the Dutch brig. That is, in prison. His coffin is made of teak, a durable hardwood that has been favoured for shipbuilding for over two thousand years. This is speculation on my part. It is anybody’s guess why Joyce actually chose to farce these pages with a plethora of Dutch terms. The present paragraph contains more than a dozen:

nu goed, nou goed : all right

de Here : the Lord God

’t is goed : it’s all right

naar de : to the

liever : rather : sweeter, dearer. Also German Lieber : beloved, dear one.

koorts : fever. Also German kurz : short.

grondwet : constitution. The allusion to public bodies voting themselves out of existence is surely an allusion to the passing of the Act of Union in 1800, in which the Irish House of Commons and House of Lords voted themselves out of existence. The act had been rejected the previous year, but widespread bribery was resorted to to ensure that it passed the second time. The Act of Union 1800 represented the biggest alteration of the British Constitution since the union of the English and Scottish crowns in 1707. The phrase town, port and garrison evokes the Tom-Dick-and-Harry motif that represents HCE’s two sons: Shem & Shaun, and the Oedipal Figure who embodies both of them. This phrase seems to be most closely associated with the town of Dover in Kent―near the southeast bluffs of the stranger stepshore. It was while holidaying in nearby Sussex in 1923 that Joyce conceived of HCE. The thinghowe referred to a few lines above is the Thingmount, the hill close to the future site of the Parliament buildings where the Vikings held their assembly.

voorschot : advanced money, loan. Is this an allusion to the bribery that secured the passing of the Act of Union?

voorschoot : apron. A recurring motif in Finnegans Wake is the butcher’s or bishop’s apron or blouse. The Butcher’s Wood is in the Phoenix Park. In Sheridan Lefanu’s The House by the Churchyard, Dr Sturk is attacked by Dangerfield and left for dead in the Butcher’s Wood, though he later makes a miraculous recovery of sorts. Joyce’s father, John Stanislaus Joyce, was also attacked in the Butcher’s Wood, an encounter that is said to have provided his son with the basis for the encounter between HCE and the Cad (and all other oedipal encounters in Finnegans Wake). According to John Gordon, bishop’s apron was a pejorative name for the Union Jack, which is entirely relevant in the context of the Act of Union. Taken together, bishop’s apron and butcher’s apron allude to the British church and state and their subjugation of Ireland (Gordon 158.30). Note also that the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169 was authorized by the only English Pope Adrian IV (Nicholas Breakspear).

schoot : lap, womb (of time), bosom (of the Church)

maat : measure, size : metre, bar (in music) : mate, partner

maatschappij : company, corporation, society, community

scheepsmaat : ship mate

kip : hen. Biddy Doran, the hen who discovers the Letter in HCE’s burial mound (ie the kitchen midden behind his tavern).

ei : egg. As laid by hens. Symbols of rejuvenation.

een nieuw pak : a new suit (of clothes). This anticipates the epic tale of Kersse the Tailor and the Norwegian Captain from II.3. cuttinrunner on a neuw pack of klerds also means cut a new pack of [playing] cards. John Gordon suggests that cutting the deck in a new pack of cards signals a new deal―another symbol of rejuvenation. To cut and run is to flee in haste. The expression is of naval origin, referring to the cutting of the anchor’s cable. A cutter is a small naval vessel designed for speed.

kleed : garment, dress

wacht even : wait a minute!

kerrie: curry.

curry which they call kerry ―Joyce, Letters I 256 (1 July 1927 to Nora’s uncle Michael Healy, speaking of the Dutch)

knol: tuber (eg potato)

bek: mouth (of an animal)

hunebed : megalithic tomb, giant’s grave

The Giant’s Grave

HCE’s grave is clearly that of a giant:

... a protem grave in Moyelta of the best Lough Neagh pattern, then as much in demand among misonesans as the Isle of Man today among limniphobes. Wacht even! It was in a fairly fishy kettlekerry after the Fianna’s foreman had taken his handful ...

The Dindsenchas, or “lore of places”, is a literary genre that was once very popular in Ireland. It comprises stories in both prose and verse that purport to explain how various places and features of the Irish landscape came to be or how they acquired their traditional names. Although many of these stories were written down, it is thought that the dindsenchas was essentially an oral tradition, which has continued to inform the country’s folklore down to the present day.

The dominant allusion in these three lines of Finnegans Wake is to one of Ireland’s best-known folk-tales, which explains how Lough Neagh, the Isle of Man and the Giant’s Causeway came to be. The central character is Finn MacCool, the leader of the Fianna, a legendary band of warriors in ancient Ireland. In his Legendary Fictions of the Irish Celts (1866), the folklorist Patrick Kennedy recounts the following tale:

This beautiful sheet of water issued from a spring well which only waited an opportunity of being left uncovered, to send forth a mighty flood. The inhabitants of the neighbourhood, aware of the danger, kept it securely covered, till at last one luckless gossip walked off with her pitcher, forgetting to replace the smooth round flag, and in consequence the water burst forth in such a volume that the poor woman was drowned before she reached home. Incredulous readers objecting to this mode of lake-making, have only a choice between it and another theory somewhat less probable.

Fion Mac Cuil having routed a Scotch giant with red hair, was pursuing him eastwards, but the canny Scotch monster was rather more fleet of foot than his Irish rival, and was outrunning him. Fion, fearing that he might reach the sea and swim across to Britain before he could overtake him, stooped; and thrusting his gigantic hands into the earth, tore up the rocks and clay, and heaved them after the Albanach [Scotsman]. As Fion miscalculated height and distance, the mighty mass which had filled the whole bed of the present lake, launched from his hands, flew past the giant at a considerable height above his head, and did not lose its impetus till it came over the mid sea. There dropping, according to the laws of gravitation, it formed an island, afterwards called Man, from its Danaan patron, Mananan, son of Lir. ―Kennedy 280

Kennedy heard another version of the tale from Jimmy Reddy, a young shanachie (seanchaí or story-teller) from County Wexford:

The great Irish joiant, Fann Mac Cuil, lived to be a middle-aged man, without ever meeting his match, and so he was as proud as a paycock. He had a great fort in the Bog of Allen, and there himself and his warriors would be playing soord and pot-lid, or shootin’ bowarras, or pitchin’ big stones twenty or thirty miles off, to make a quay for the harbour of Dublin. One day he was quite down in the mouth, for his men were scattered here and there, and he had no one to wrestle or hurl, or go hunt along with him. So he was walking about very lonesome, when he sees a foot-messenger he had, coming hot-foot across the bog. “What’s in the win’(wind)?” says he. “It’s the great Scotch giant, Far Rua [Redhaired Man], that’s in it,” says the other. “He’s coming over the big stepping stones that lead from Ireland to Scotland, [Footnote: The Giants’ Causeway, of which there are now visible only some slices at the two extremities. Those trustworthy chroniclers, the ancient bards, affirm that it is the work of the ancient Irish and Scotch men of might, laid down to facilitate their mutual visits.] and you will have him here in less than no time. He heard of the great Fann Mac Cuil, and he wants to see which is the best man.” “Oh, ho !” says Fann, “I hear that the Far Rua is three foot taller nor me, and I’m three foot taller nor the tallest man in Ireland. I must speak to Grainne about it.”

Well, it wasn’t long till the terrible Scotch fellow was getting along the stony road that led across the bog, with a sword as big as three scythe blades, and a spear the lenth of the house. “Is the great Irish giant at home?” says he. “He is not,” says Fann’s messenger : “he is huntin’ stags at Killarney; but the vanithee [bean an tí = woman of the house] is within, and will be glad to see you. Follow me, if you please.” In the hall they see a long deal (fir) tree, with an iron head on it, and a round block of wood, with an iron rim, as big as four cart wheels. “Them is the shield and spear of Fann,” says the messenger. “Ubbabow!” says the giant to himself.

To make a long story short, Finn tricks Far Rua into thinking that the Irish are much bigger and stronger than they actually are, even posing as his own infant son to sell the ruse. After several adventures in which Far Rua is bested by the locals, he has finally had enough:

He got up, and rubbed his poor skull, and looked very cross. “I suppose Fann won’t be home to-night.” “Sir, he’s not expected for a week.” “Well, give the vanithee my compliments, and tell her I must go back without bidding her good bye, for fear the tide would overtake me crossing the Causeway.” ―Kennedy 203–206

In Finnegans Wake there are at least two other allusions to the first of these folk-tales:

RFW 039.12–13: Fenn MacCall and the Serven Feeries of Loch Neach

RFW 239.18–22: Yet is it, this ale of man, for him, our hubuljoynted, just a tug and a fistful as for Culsen, the Patagoreyan, chieftain of chokanchuckers and his moyety joyant, under the foamer dispensation when he pullupped the turfeycork by the greats of gobble out of Lougk Neagk.

There are a few other allusions to the Giant’s Causeway in County Antrim. See FWEET for the complete list.

limniphobes Ancient Greek λίμνη + φόβος : lake + fear. The Isle of Man has no lakes.

misonesians Ancient Greek μῖσος + νῆσος : hatred + island. Lough Neagh has (almost) no islands. In a letter to his son Giorgio and daughter-in-law Helen, Joyce wrote the following about a traditional Irish song:

Little Red Fox (An Modereen Ruadh) a charming little fanciful song. Moore (Thomas) used it in the melody Let Erin Remember. This melody is about Lough Neagh under which there is said to be buried a kind of Atlantis. Others say Finn MacCool in anger took a sod of turf out of Ireland and flung it in the sea, thus making 1) Lough Neagh 2) Isle of Man. ―26 February 1935 (Letters III 348)

In Irish mythology lakes were often seen as entrances to the Otherworld. Hence the belief that there was a city buried in Lough Neagh.

- Moyelta Irish Magh Ealta : Plain of Flocks. Also known as Sean Magh Ealta Éadair or The Old Plain of the Flocks of Howth (RFW 014.09), this was the old name for coastal plain that lies north of the Dublin Mountains. In the mythological history of Ireland, when Partholon arrived in the country after the Flood, this was the only treeless plain on the island. He named it from the flocks of birds that sunned themselves on it. The Partholonians were wiped out by a plague and buried in Tallaght, the name of which is derived from the Irish támh + leacht : plague + grave stone.

Alaric the Goth & Attila the Hun

The closing lines of this paragraph refer to

... and there now, brown peater everipple (may their quilt gild lightly over his somnolutent form!), Whoforyou lies his last, by the wrath of Bog, like the erst curst Hun in the bed of his treubleu Donawhu.

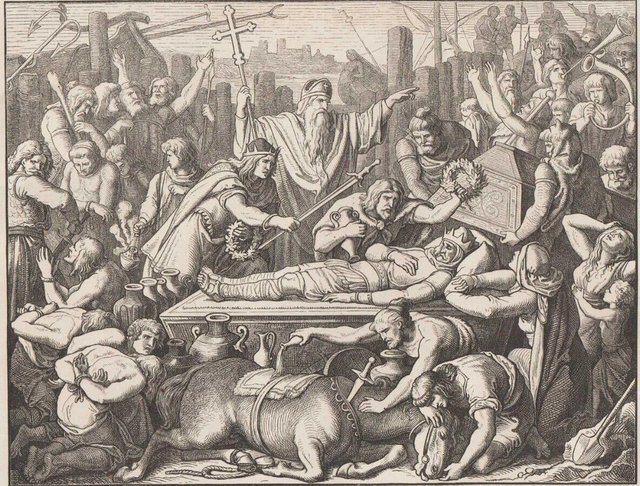

HCE is not the only hero to be buried in a watery grave. According to tradition, Alaric, King of the Visigoths, was buried in a grave that was dug in the bed of the River Busento in Italy. When Alaric was a child, the Visigoths dwelt in Dacia (modern Romania), north of the Danube. In the late 4th century, the expansion of the Huns drove them across the Danube into the Roman Empire. War with Rome culminated in 410, when Alaric sacked and looted the city. He then moved south and in the early months of 411 he fell ill and died outside the town of Consentia in Bruttium. The Busento was temporarily diverted so that a grave could be dug in its bed. There Alaric was buried with some of the vast treasure looted from Rome. The river was restored to its original bed and the gravediggers were executed to keep the exact location of the grave a secret. The story is recounted in Chapter 30 of Jordanes’ Getica.

The story of vast treasure being buried in the bed of a river also brings to mind the German Nibelungenlied, on which Richard Wagner based his operatic tetralogy Der Ring des Nibelungen. Siegfried’s hoard, which he takes from Fafnir the dragon, is buried in the Rhine.

Attila the Hun is also referenced in this section. According to Jordanes, Attila died on his wedding night on the Great Hungarian Plain, north of the Danube. He was buried in a triple coffin of gold, silver and iron, and filled with treasure. The gravediggers were executed to keep secret his place of burial. The character of Etzel in the Nibelungenlied is based on him.

The story of a river being diverted to cover his grave is also told of Attila (Ecsedy 133–134). It is possible that Jordanes’ account of the death of Alaric (Chapter 30 of his Getica) was confused with his account of the death of Attila (Chapter 49). The river in question is usually identified as the Tisza, though Ildikó Ecsedy is unwilling to rule out the Danube. It would be interesting to know what Joyce’s source for these details was.

- wrath of Bog Serbo-Croation Bog : God. And Russian: Бог : God. Attila was known as the Scourge of God (Latin Flagellum Dei), which is sometimes loosely translated as Wrath of God.

- German Donau : Danube. Donawhu also refers to the O’Donoghue, a Gaelic chieftain supposedly living in a palace under Lough Leane in Killarney. It is said that his emergence from the water presages a good harvest. This is another example of the mythical idea that the god of the Otherworld dwells at the bottom of a lake.

This passage also weaves together several other allusions to water, rivers, bogs, peat, and the turf-brown water of Anna Livia (RFW 153.20). Remember how the allusion to the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields on the opening page of the book also had a watery element: oystrygods gaggin fishygods (RFW 003.23). The Blue Peter, a flag displayed by a ship that is about to sail, continues the naval theme running through this paragraph.

old knoll and a troutbeck HCE & ALP as hill and rill. A knoll is a hill, a beck is a stream. Old Noll was Oliver Cromwell’s nickname. There is an actual river in the English Lake District called the Trout Beck.

everipple A pun on the condom brand name Neverrip. They are mentioned, appropriately enough, in the Circe episode of Ulysses.

Whoforyou Humphrey, but it also hints at the possibility that someone else is being buried as a substitute for HCE. In Islamic tradition, it is said that Simon of Cyrene did not simply help Jesus to carry his cross : he was actually crucified in his place. In The Golden Bough James Frazer describes ancient customs in which the ritual slaying of the king―which originally involved literal regicide―was altered so that a substitute was slain in place of the actual king.

And that’s as good a place as any to beach the bark of our tale.

References

- Joseph Campbell, Henry Morton Robinson, A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake, Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York (1944)

- Robert B Douglas (translator), One Hundred Merrie and Delightsome Stories, Volumes 1–2, Léon Lebèque (illustrator), Charles Carrington, Paris (1899)

- Robert B Douglas (translator), One Hundred Merrie and Delightsome Stories, Volume 1, Volume 2, Andrew Machen (editor), Carbonnek (1924)

- Ildikó Ecsedy, The Oriental Background to the Hungarian Tradition about “Attila’s Tomb”, Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientarum Hungaricae, Volume 36, Number 1, Pages 129–153, Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest (1982)

- Daniel Ferrer, VI.B.17: A Reconstruction and Some Sources, Genetic Joyce Studies, Issue 15, Centre for Manuscript Genetics, University of Antwerp, Antwerp (2015)

- David Hayman, A First-Draft Version of Finnegans Wake, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas (1963)

- Eugene Jolas & Elliot Paul (editors), transition, Number 3, Shakespeare & Co, Paris (1927)

- James Joyce, Finnegans Wake, The Viking Press, New York (1958, 1966)

- James Joyce, James Joyce: The Complete Works, Pynch (editor), Online (2013)

- Patrick Kennedy, Legendary Fictions of the Irish Celts, Macmillan and Co, London (1866)

- Danis Rose, John O’Hanlon, The Restored Finnegans Wake, Penguin Classics, London (2012)

Image Credits

- The Teak Coffin: Safety Coffin: Life-Preserving Coffin in Doubtful Cases of Actual Death, Christian Henry Eisenbrandt (designer), C Burton (illustrator), Baltimore, Maryland, Public Domain

- The Safety Tomb of Timothy Clark Smith: Evergreen Cemetery, New Haven, Vermont, © Geoff Howard (photographer), Panoramio, Creative Commons License

- Irwin’s Glass-House on Potter’s Alley in 1845: M S Dudley Westropp, Irish Glass, Herbert Jenkins Limited, London (1920), Page 28, Advertisement (1845), Public Domain

- Henry Grattan Addresses the Irish House of Commons in 1780: Francis Wheatley (artist), Lotherton Hall, Yorkshire, Public Domain

- The Giant’s Causeway, County Antrim: © sagesolar (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Lough Neagh: © Conall (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Isle of Man: Sentinel-2, Copernicus Programme, European Space Agency, Creative Commons License

- The Burial of Alaric: Eduard Bendemann (engraver), Public Domain

- The Meeting of Leo the Great and Attila: Raphael (artist), Stanza di Eliodoro, Raphael Rooms, Apostolic Palace, Vatican City, Public Domain

Useful Resources

- FWEET

- Jorn Barger: Robotwisdom

- Joyce Tools

- The James Joyce Scholars’ Collection

- FinnegansWiki

- James Joyce Digital Archive

- Finnegans Wake Notes

- John Gordon’s Finnegans Wake Blog

- James Joyce: Online Notes