To help the cultural sector, historians should make films

This week I was inspired by my colleague @hourofhistory's post about podcasts. I think he's right that podcasts present a low-cost way to generate historical content that, thanks to the internet, can reach wide audiences. Historians should be making podcasts. I also think that historians should be making films.

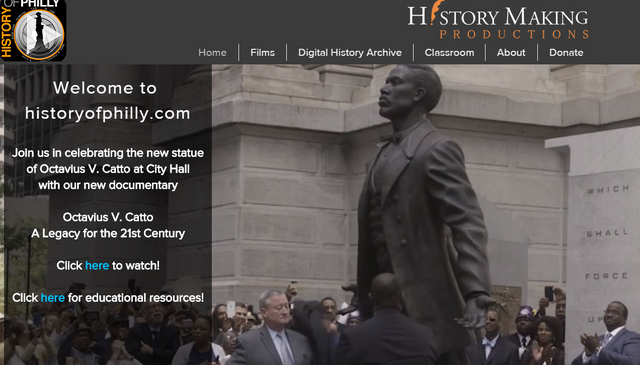

History Making Productions is a private company in Philadelphia that makes documentary films about the city's history. Wouldn't it be great if instead of contracting this work out to private companies historical institutions could make their own film content?

Film is a uniquely powerful medium due to its ability to combine visual, textual, and audio components. Platforms like YouTube and Steemit's DTube make it easier than ever to share original films online. Film is thus a uniquely engaging way to produce accessible historical content.

Unfortunately, academic historians have long resisted working with film for a number of reasons. But, in my opinion, each point of resistance is also a point for why historians should embrace film.

Here are common excuses for why historians don't work with film, and why I think they are actually reasons for historians to work with film.

1. Film only produces pop history

Sure, the History Channel has made some bad stuff, but what's wrong with well-researched pop history? Doesn't pop just mean popular? Isn't that what the historical sector wants? Making history entertaining doesn't necessarily make it bad. Making history entertaining gets new people interested in the subject, creating new and/or more engaged patrons of the historical sector.

2. Film is still an unfamiliar--and thus uncomfortable--tool for historians

While a growing number of historians are considering film in their research, it is by no means widely accepted. Many historians are still uncomfortable conducting film analysis, nevertheless making films themselves. The only way to change this is to make film making part of historical training.

With the growing ability to share films online, it should be taught as a legitimate way to spread historical knowledge. As the historical sector necessarily becomes more digital, it needs to consider more than just making a website as a depository for scanned images and clips. Films allow for an engaging way to digitally present historical materials in a narrative form. Instead of just being taught to craft historical narratives in text form, we should be taught to make entertaining and educational connections visually.

3. Film permits "audiences to engage with the past in a way which was not dependent on historical scholarship."

The historian Tony Barta wrote the above quote in his 1998 work, Screening the Past: Film and the Representation of History. According to Barta, this ability for historical knowledge to exist independently from the academy terrified professional historians. For him, and for me, this independence is what makes film so exciting.

The popular online media company BuzzFeed has recently began making historical films. Their video, "Was Ben Franklin in a Sex Cult?" from their series "Ruining History" has over 2.5 million views on YouTube. The historical true crime exploration of "The Ghastly Cleveland Torso Murders" was viewed over 1.5 million times in just three days.

Much of the BuzzFeed historical videos involve narration over graphics, a simple and entertaining way to illustrate the past.

None of the people involved with these videos are professional historians. Instead, they're filmmakers.

Of course, these BuzzFeed videos are supported by a pre-established audience who follow the company's online content. The view counts of their historical videos, however, prove that something about the content is connecting with the audience. These videos make history fun.

Filmmaking can help the historical sector

What if, as part of a larger effort to become more digital, an historical society made a web series? Doing this would require a digital savvy staff with the necessary technical and creative skills. What if historians were trained in these skills? What if graduate history programs taught us how to operate camera equipment and video editing software? What if making a movie that combined historical and contemporary film clips, narration, photographs, graphics, and interviews was just as acceptable as writing a research paper?

Teaching these skills would take time and resources, but I think it's worth it. What do you think? What would we have to sacrifice in order to make film a bigger part of public history?

Every time I see a short history video that I'm in, like this recently produced one on Benjamin Franklin and Joseph Breintnall, I feel grateful that the word is being spread in a mode that is both accessible and interesting. But I also see a lot of room for what might be called improvement. So, yes, a solution is to become a video producer or to work with one. The university has capacity to teach all of the needed skills, but the schools and departments are in their silos.

How to fix that?

I definitely don't have a solution for "de-siloing" the university, but I also want to pose another question. If we don't provide filmmaking training for public historians, why does the field term documentarians as part of our community? Do we actually see them as historians or associate them with ahistorical entertainment? Entertaining history ((or pop history as you term it)) expands and engages audience--the main tenets of public history work. Once again, the professional history world decides who is "in" based upon their usage of traditional mediums.

And the unfortunate irony is that Temple University produces public historians in one school and documentary producers in another! So whose fault is the persistence of that disconnect?