Polanski's Chinatown

Film noir is not so much a genre of film but an ever expanding category of films that use symbolism from the casual to the metalevel, oftentimes to show the darkness that is constant in the subtext. Film noir is known for its stories of traumatic experience in society. The films that defined noir (darkness of the modern human experience, for all intents and purposes) stretched from the forties to the sixties, and films that capture the essence of noir after it is abandoned can be considered neo noir with its heightened violence and continual theme of a labyrinth-like journey. Director Roman Polanski’s second Hollywood film Chinatown is considered to be one of the best films ever made for its bold, sparse aesthetic and daring subject matter. The film uses the vessel of film noir to artfully depict the violent world of the nineteen thirties and cryptically explains the corruption that built Los Angeles. Chinatown is about corruption, both starting with C and ending in N, as the word is brought up in conversations as a reference to Jake (Jack Nicolson’s character) and other characters being crooked cops.

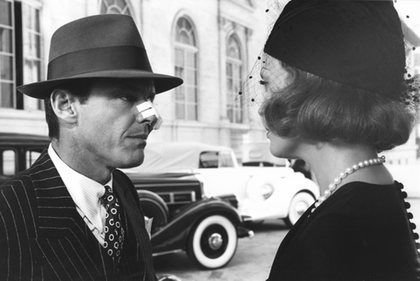

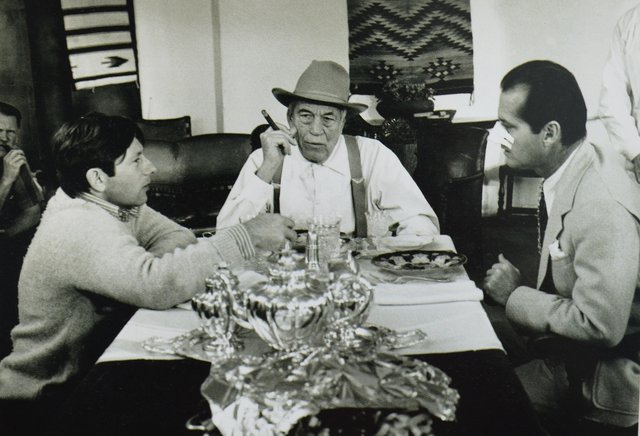

The use of camera in Chinatown is extraordinary as it lures in the viewer stylistically in its editing and minimal transitions, but it also manages to mimic not only the cinematography but the heavy cameras of early Hollywood than would barely pan. The opening credits contain title slides imitating the style of the thirties, and then the film opens with hands flipping through multiple photographs that zoom out into the world. The movie has a timeless feel in its aesthetic. The various tracking shots in Chinatown are also reminiscent of Stanley Kubrick’s films of the 70’s for its virtual realism and pace in terms of how the story unfolds. Costume-wise, Jack Nicolson’s profile and use of brimmed hat land him as perfectly casted into film noir role; his portrayal of Private Investigator Jake Gittes mirrors veteran film noir actors that are referenced in the film such as Humphrey Bogart. Chinatown, interestingly enough, is about water, the most essential thing to life, and how it has been subtlety turned into a tool by the elite to manipulate society. There are water-motifs in every scene for almost three quarters of the film, where there is either water, or images of water in the background or water is being mentioned in conversation. This motif is used to show how fluid our history is and how quick politics can brutally shift under the surface. Chinatown’s storyline also contains a deep conspiracy which portrays the reality of the Los Angeles water-wars. This is introduced in the underlying story when the water traffic of Southern California becomes privatized by John Huston’s character of Noah Cross. In the beginning of the story, there is a sort of false flag introduced to the citizens as a water shortage that is discovered later as a ploy orchestrated by Cross to expand his monopoly. Screenwriter Robert Towne denies that the characters in Chinatown, Hollis Mulwray and Noah Cross, are representative of the real-life William Mulholland (Towne, film commentary) but is certainly implied William Mulholland is depicted in the noble character of Hollis Mulwray (who dies 15 minutes in the first act), and inverted into real-life gangster, Claude Mulvihill. This demonstrates the exploitation of the environment and lust for power “condensed into the singular and singularly monstrous, Noah Cross.” (22, Brook)

Chinatown contains a narrative full of corruption like most film noir, but with more edge than those during the first wave of film noir and with more deserving attention to feminine perspective, which women had no rights at all in the 1930s. In terms of Faye Dunaway’s character Evelyn Mulwray, she is not a typical femme-fetale, even though there is an impression of her inscrutable character, somehow lying and hiding something throughout the entire movie. At the end it’s revealed that she and her murdered husband, Hollis, were among the moral characters. Before the characters clash at the end of the film, Jake discovers right before he nearly gives up on Evelyn’s secrecy and hands her over to the police, just how deep the secrets go with her; Jake empathizes and decides, in a pressing moment of realization, to help her escape Los Angeles with her daughter that is also her sister. Evelyn’s trauma from her parasitic-incest father allowed little trust from Jake or from any men in her life, other than the foreign-Chinese servants who due to their social standing try and fail in saving Katherine from her father in the end. It should be mentioned that themes of classism and racism was also used in noir in rare occasion like in Stanley Kubrick’s first studio film, The Killing, but in Chinatown the societal racism in protagonists like Jake are hinted at while made clear in dialogue, making the world more dimensional from its use of subjective characters consciousness. The distinctive story arch of Chinatown is similar to films that came later such as Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, where the movie unfolds as the reverse of the hero’s journey, where the character is devastated in the conclusion in contrast to the beginning when he considered himself fully realized.

Chinatown is one of the only screenplays that Roman Polanski didn’t write or alter. The screenplay was so rich in its story that he knew it couldn’t be messed with by the director, with the exception of its notorious conclusion. Initially, screenwriter Robert Towne heavily disapproved of Polanski’s drastic end to his story. Chinatown has an utterly dark but appropriate ending that Polanski added in last minute. Evelyn’s demise by the police, unknowing of what happens to her beloved Katherine; we, as the audience, witness Noah Cross suggestively take his incest granddaughter away, hinting that he will do the same thing to her as he did to Evelyn. Cross pretends he is sad to see Evelyn die and Jake is distraught. This ending is not nihilistic as it may seem. The ending instead speaks to the amount of corruption that continues due to the misplaced belief in authority figures and suppression of humanity because of society. We are like Jake throughout the film as we don’t know how high the level of power and corruption goes, where it reaches beyond materialism into psychopathy and this is seen in towards the end of the film when Cross explains to Jake he doesn’t blame himself for Evelyn’s past, because at a certain point in one’s life they are “capable of anything”. Furthermore, the police that are owned by Noah Cross turn Jake loose to sweep the situation under the rug, insisting they’re doing him a favor. There is no moral code in this world when there is an exception from morality. Had Chinatown not contained Polanski’s bereft and gloomy ending; the message would not be memorable or relevant, and there would be no message of the kakistocracy that is pervasive through civilization. If Evelyn escaped, it would disregard the perpetual corruption of the criminal elite and generational trauma it creates. Polanski demonstrates his natural sense of story direction even further than his previous film Rosemary’s Baby, which also exceptionally dealt with heavily topics of mind-control and Satanism. Because of its unique narrative and style, Chinatown carried the torch for film noir and is a reminder of vices that the sunny world of California contains in its darkly haunted history.

Brook, Vincent. Land of Smoke and Mirrors: A Cultural History of Los Angeles; Rutgers University Press; 2013

Muller, Eddie Dark City: the lost world of film noir, - St. Martin’s Griffith; p 82, 83. 1998

Polanski, Roman Chinatown film commentary by David Fincher and Robert Towne

Congratulations @armanzahedi! You have completed the following achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP