When You’re Small Enough to Hide Under the Couch and then You’re Not.

When You’re Small Enough to Hide Under the Couch

By me…

When I was a little kid, my sister and I shared a bedroom at 612 East County Line Road. The house only had two bedrooms—one for our parents and one for us— tucked between them was the bathroom.

The rooms were small by today’s standards, but to us they were expansive—whole worlds to imagine within. We moved into that house when I was about two or three, and from that moment on, it was home. Not just a house, but the center of a child-sized universe.

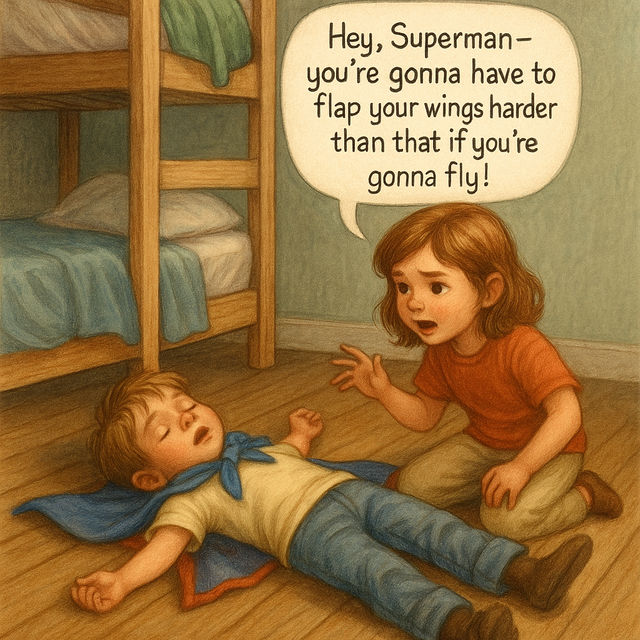

We had bunkbeds—mine on the top, my sister’s on the bottom because she was so small. She was two years younger than me, and I think a little smarter too. My mom tells me that one day, while she was in the kitchen making lunch for the two of us, she heard a tremendous thump—the unmistakable sound of a non-bouncing, large watermelon hitting the floor.

She ran into the room and threw open the door—and there I was, sprawled out on the floor, unconscious or at least dazed, a towel tied around my neck like a Superman cape. My sister was still in her bed, leaning over me, trying to rouse me with the stern voice of a coach:

“Hey, Superman—you’re going to have to flap your wings harder than that if you’re gonna fly!”

I have no memory of it. None at all. But I’ve never tried to fly since—not once. Some lessons stick, even when the memory doesn’t.

The bedroom was alive with toys and imagination: Lincoln Logs, Matchbox cars, a spirograph with its swirling geometric magic, and Rock’em Sock’em Robots with their clacking plastic fists. I had a game called Battle Tops—a round plastic arena where four spinning tops would collide, and whichever one flew out lost. Simple joy. My sister had her baby dolls and little ovens, the kind you could really bake with. And of course, she had me—the boy who could almost fly.

I remember the injustice of going to bed while it was still light outside—how it never seemed fair. And yet, once the sun dipped and shadows crept in, I wasn’t exactly eager for darkness either. I had it fixed in my head around five or six years old that wolves lived in my closet. You couldn’t see them—but they were there. Always just out of sight, waiting. The closet door had to be shut tight. Thankfully, I had my defenses: a wolf-proof blanket, and Bozo the Clown—my homemade ragdoll. My mother had painted his face and sewn his hair by hand. You could grip him by the feet and swing. He wouldn’t hurt a fly, but he made a loud pop when he hit something. That was enough for me. I don’t know where that doll is now. I kept him for the longest time. Funny how things disappear when you move.

My dad turned bedtime into theater. He had a way of closing the door like he was leaving, only to remain just inside the shadows. Then would come the rumble—“Fee-fi-fo-fum…” or his Frankenstein voice, slow and monstrous. We’d scream, but it was the best kind of scream—the safe kind. The kind where you knew he was there, and nothing could really happen to you. It was pretend. It was love dressed up in drama.

There was always light outside the window, filtering in from next door. That was Uncle Ben’s house—Pop’s brother—the one with the painted dogwood tree (but that’s another story). It was where my cousins George and Mary Lou lived, along with Aunt Helen. For some reason, I always called George “Uncle George,” even though he wasn’t. He helped me learn to ride a bike—steadying me on the smooth asphalt until I could balance on my own. And Mary Lou? She patiently drilled me on my times tables, over and over, until I got them down.

And then, of course, there was that cat—the orange one that would lick you until you were soaking wet, not out of affection, but because it didn’t want to get hair on its own tongue. It wasn’t love. It was strategy.

Nana’s Purple Kingdom

Across the street—and catty-corner from Uncle Ben’s—was my sanctuary: Nana and Pop’s house at 621.

That house was full of purple. Nana dyed everything she could. If it wasn’t purple when she bought it, it would be soon. She’d head to the 24-hour laundromat on Kennedy Boulevard late at night with towels, tablecloths, and bargain-bin throw rugs, and emerge with them soaked in lavender or plum. Purple was her color. Her comfort. Her expression. Butterflies and Purple.

It’s hard to describe how many variations of purple there really are—until you’ve spent enough time with an expert like Nana. Lilac, eggplant, orchid, mauve, grape, and whatever shade came out of that dye machine when the water temperature wasn’t quite right. I think it might even be one of the reasons I seem a little color-blind now when I pick out clothes. I grew up around so much purple, everything else just kind of blends in.

Her upstairs bedroom felt like royalty. Not a proper canopy bed, but curtains that draped across the headboard like window treatments, transforming the space into something elegant and soft. Hanging above the pillows was a lamp I thought was the prettiest in the world—a Lucite teardrop, full of tiny flecks of color. It glowed softly, and when you looked up from beneath it, the world turned into a kaleidoscope.

When I got to sleep in Nana’s bed, I’d lie there under the drapes, staring at that lamp and singing softly to myself. I only knew a few songs—“Let the Sunshine In” and “You Are My Sunshine.” I didn’t know who wrote them. I just knew they made me feel warm inside. I still sing them to my own children.

Eventually, I started sleeping in the bedroom at the end of the hallway. It had green carpet, soft purple sheets, and an air conditioner in the window that kept it cool and quiet. One window looked out over the backyard. The other faced the road and railroad tracks. It was dark, but I wasn’t afraid. The wolves couldn’t follow me across the street, and besides—Pop’s room was just across the hall with a shotgun. That was all the security I needed.

Still, Nana understood. One night, without saying a word, she came into my room and plugged in a Lucite nightlight—red, glowing, shaped like a flower. “I thought you might like this,” she said gently. That was all. She never mentioned fear. But she knew. That little nightlight became my companion. I’d lie there in bed, staring at it until the rest of the world faded, the soft red glow pulling me into sleep like a lullaby without words.

The upstairs hallway had floor vents. The bathroom had them too. The house wasn’t built to heat both floors directly, so warmth rose up from below. Every bedroom had a vent, but the hallway and bathroom vents were the best. On Christmas or Thanksgiving, if I got sent to bed early, I’d sneak out and lie next to it. I could hear the adults downstairs—talking, laughing, wrapping gifts. It was like peering into another world through the grate in the floor, and I loved it.

The stairs were carpeted, except where the floor vents opened. At the bottom was a landing, and then one step to the left led into the living room. A big mirror once hung on that landing—until the day Nana fell down the stairs. The glass shattered, and massive shards cut her badly. She was hurt—but she healed. And when she did, another mirror went up in its place.

Nana had always been someone who took charge. That landing was her photo spot—where holiday pictures and family portraits were staged in front of the mirror, year after year. And a little thing like being nearly killed was not going to stand in the way of her vision.

When we were little, we learned how to conquer those stairs. I remember being maybe two or three, belly down, sliding one step at a time. As I got older, I’d bump down on my backside—bump, bump, bump—all the way to the bottom, where Pop would be waiting.

The living room was cozy, carpeted in a pink-wine color (another variation of purple). Pop’s green vinyl recliner sat near the TV. Nana had a purple sitting chair. and at the back of the living room A deep purple almost blue, couch rested against the wall. On top of the TV was a Roseville vase—always filled with flowers. I still have it.

About the Couch, There was a couch in the back of Nana and Pop’s living room—a deep plum, almost blue. It wasn’t anywhere near the TV. It sat apart, in a quieter section of the room, a place meant for talking—not watching. I don’t remember ever seeing anyone lie on it. It was more like a perch for conversation, coffee cups, and pipe smoke. For grown-ups.That couch barely cleared the floor. Maybe six inches, tops. But when I was little, that was enough. I could slither under it on my belly and disappear—completely hidden. During hide and seek, it was my go-to spot. No one ever found me unless I gave myself away by giggling. It felt like a secret world just big enough for me.

Then one day—after a long stretch without playing hide and seek—my sister and I decided to play again. She began counting in the dining room, loud and clear, while I ran off to hide. My plan was simple: go back to the old faithful spot.

I dropped to my belly and slid toward the couch.

But I didn’t fit.

I pressed forward, trying to shimmy in like old times, but my shoulders caught. My head fit, maybe even my chest, but not the rest. I couldn’t go any further.

So I backed out quietly, settled for the dining room table instead, and waited. From where I was lying, I could see into the other room.

And then I saw her.

She dropped to the floor and, without effort, slid right under that same plum couch—my hiding place.

And that’s when it hit me.

It wasn’t the couch that had changed.

It was me.

That may have been the first time in my life I felt time. Not on a calendar, but in my bones. In the way the world stayed the same, but I no longer fit in it the same way. I had grown—and without knowing it, left something behind.

I guess that’s what made Pop’s chair that much more important. On the right hand side of that chair there was a stand with an ashtray on it grooved for pipes and a space for a pouch of loose tobacco. On the other side there was a stand with the TV guide. Though the need for a TV guide in the world of my grandfather, where he watched the same thing all the time seems silly now to think about it..

at any rate even though I could no longer fit under the couch…

There was always room in Pop’s chair for me. I’d climb up next to him and nestle into the crook of his arm. Eventually when we got older he got a dog named Feefee who tried to compete for space but we would always win. Pop smelled of cherry pipe tobacco. He used to smoke unfiltered Lucky Strikes and Camels too, until the heart attack. After that, Nana gave him an ultimatum: “Quit, or &@@#%^ .” He quit. But not the pipe.

Nana smoked too, as did most of our family. Dad smoked Marlboros. Mom smoked Newports. But Nana quit because of me. Around 1970, after watching a commercial about lung cancer during one of my cartoons, I climbed up into her lap and looked her in the eyes. “I don’t want you to die,” I said. “You have to quit.” She never smoked again.

My Pop was more than a recliner and a quiet protector. He was my mentor. He made me bicycles and swings. He took me around with him sometimes, just running errands or going to town. I remember once he brought me along to visit the township where he used to work—just to talk to “the guys” after he retired. It was the early ’70s, and I was in that phase where I didn’t want to get a haircut. My hair was longer than he liked, and I guess it didn’t go unnoticed.

Mom told me later that Pop had gotten pretty upset. One of the men at the township said something to him—something like, “Hey, who’s your granddaughter?”—and Pop didn’t take it well. He told Nana, who told Mom, who told me that Pop said he wasn’t going to take me back again until I got a haircut. It wasn’t mean-spirited. He just came from a different world. One where how you looked said something about your family.

But even so—he still took me hunting. He got me my first license. He gave me my first real shotgun—an over-under Springfield, .22 on top, .410 shotgun on the bottom. I still have the license. Around age twelve or thirteen, I graduated from the BB gun, and Pop made sure I took the hunter safety classes. He showed me how to shoot, how to carry, how to walk the woods like a man.

We’d hunt with Uncle Jack—his sister Dot’s boy—and old Art Maxin, the half-blind former model T mechanic from Squankum Road who now fixed bicycles and lawn mowers. Art smoked cherry pipe tobacco too, as did Jack, if I remember right. The woods were filled with that sweet scent, mingling with the dampness of fallen leaves and the sharp bite of frost in the air.

Pop didn’t eat the game we caught. Too many squirrels and rabbits during the Depression had ruined him on it. He stuck to steak and ham. No fish either. His rule was simple: no fins, feathers, or fur. But he’d clean the rabbits and give them to Art, or Jack, or one of the old widows in the family Like Aunt Molly or Ella. They all knew what to do with it.

One More Thing About the Rabbits…

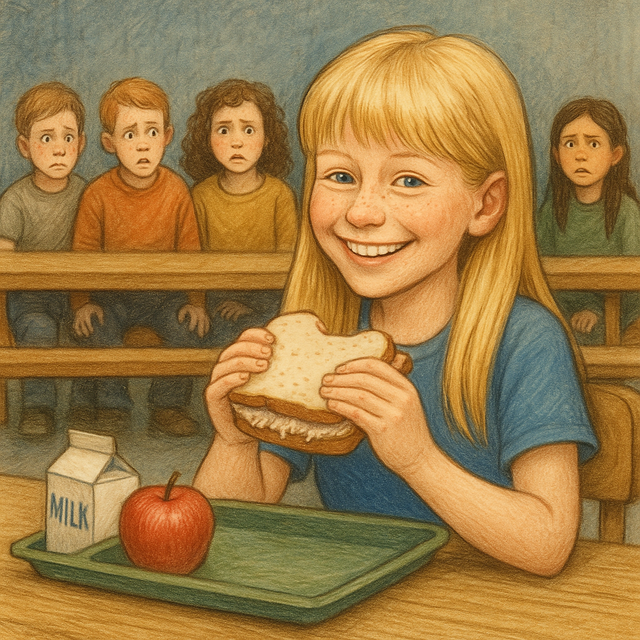

I was talking with my cousin Mary Lou—Uncle Ben’s daughter—and she shared something I never knew. Turns out Pop didn’t just bring rabbits to Art or Jack or the widows in town. He brought them to her mother—my Aunt Helen.

“Uncle Ernie would give the rabbits to my mother. I was the only one who ate it, but still, she managed to come up with different ways to make it for me. She made rabbit stew and even rabbit parm. She would also bake it and use the leftovers to make rabbit salad—like chicken salad. It made a great sandwich for school lunch. No one had a clue what it was. But sometimes she’d make a sandwich with just the leftover baked rabbit and mayo on white. For some reason, the kids figured out what it was. On those days, I had the table to myself.”

Then came the epilogue to that memory—unexpected and honest.

Years later, when Mary Lou was grown and married—living in the very house she grew up in—she said the rabbits started coming to her.

“Sure did look different before it was cooked. I knew I had to soak it in salt water. Step one, check. But now what? Well, it kinda tastes like chicken, and I like to cook chicken on the rotisserie. Step two, check. So, I put it on the rotisserie. Only problem was… it just didn’t look very appetizing.”

“Long story short—it stayed there until garbage day. Then I told Uncle Ernie, ‘Thanks but no thanks.’ My rabbit days are over.”

And he probably just nodded.

That was Pop. And that was family.

And now it was my turn.

Every house back then seemed to have a cedar post in the yard. Ours did. So did Maxin’s. So did Jack’s. Weathered, grey, sturdy—each with a single nail driven near the top. That was your cleaning post. You’d hang the rabbit by its feet, make a slit, and peel the skin down like you were turning a sock inside out. The guts came out before you ever brought it home. The kidneys went to the dogs—always.

Those posts are mostly forgotten now. People knock them over, never realizing what they were once for.

And always—there were the Wonder Bread bags. The white ones with all the little balloons and promises of vitamins and minerals. After making tomato sandwiches or whatever we packed for lunch, Pop would save the bags. So would Jack and Art. Before we headed out, they’d stuff a couple into their coat pockets. Afterward, they’d slide the dressed rabbits into those same bags and carry them home—pockets bulging with game. Sometimes we’d stop at the gas station or at John Harper’s, and there they’d be—three men standing in line with dead rabbits in bread bags. No one thought anything of it.

Pop taught me how to skin them too. It wasn’t hard—just a little messy. But it was part of growing up. Part of being trusted. Part of being included.

Have you ever been in the woods in late fall or winter? When the air is cold and clean, and the smell of decomposing leaves blends with the faint sweetness of pipe tobacco? When the fog of your breath meets the slanted morning sunlight, and you look over to see the outline of a man you admire—his smoke cloud drifting just ahead of him?

I was thirteen or fourteen when I first looked around and knew with quiet certainty: this is the world I belong to. And it’s a good one. I don’t want it to end.

And when Pop stopped hunting… so did I.

If there’s anyone, even now, who had something bad to say about my Pop—I’ve never heard it.

Pop was always Pop to me—but to many others, he was Uncle Ernie. He left his mark quietly, but deeply, especially on our family. He never drank. Not even a little. He wasn’t the kind of man to shout or command attention—but when he spoke, it mattered. His words were often witty, always kind, and somehow carried more weight for how few there were.

My middle name is Ernest. My father almost always called me that. And if I was going to grow up to be like anyone—really be someone—it would’ve been my Pop. That’s not to take anything away from my father. Not at all. In fact, my Pop was so much like my dad in how he treated me—and that was a good thing, too.

When Pop passed away, his nephew Jack—the one who hunted with us, who was always by his side—fell into a sorrow I’d never seen before. I remember talking to my mother about it, and Nana too. She told me Jack had just stopped eating. Said he’d grown so quiet. So withdrawn. He told my mom, “I just don’t think I can live like this. It’s just too sorrowful.”

It wasn’t long after Pop’s funeral that Jack died, too.

And my mother, who was not given to sentiment, said something I’ll never forget: “If anyone had ever told me someone could die of a broken heart… I don’t think I would’ve believed them. Not until Jack.”

One More Thing…

Before me, Cousin (Uncle) George and Mary Lou had bicycles that Pop and his brother Ben had refurbished, too. Nothing ever went to waste in their hands. Uncle Ben—Pop’s brother—was a typewriter repairman by trade, but a craftsman at heart. He and Pop used to salvage the metal agitators from inside old washing machines—those big twisting parts that stirred the laundry. Uncle Ben thought they looked beautiful in their own way. So they’d sand them down, paint them gold or silver, run a cord up through the center, and turn them into lamps.

Big, strange, beautiful lamps.

Nobody does that anymore.

Well… almost nobody.

Time moves on.

A few years later, when I was sixteen or seventeen, Nana and Pop found me a car—a 1972 Buick Electra 225. Emerald green. 455 four-barrel engine. Looked brand new. They’d found it in a retirement community off Route 70. I paid for it myself—$600 for the car, $600 for insurance—money I had saved, little by little, walking to the bank with my deposit book, just like Nana taught me.

That car didn’t last long.

One night after bowling, I took the back road home. Too fast. Hit a sandy patch. The car spun out and slammed into a tree.

Nobody was hurt. But the car was totaled. Gone.

A week or two later, I came home from school—hot day, early June—and there was Pop, out in the front yard, paintbrush in hand. He was in his seventies by then, standing in the heat with a gallon of baby blue rubber-based boat paint, brushing thick strokes onto a 1964 Buick Special.

Leaves stuck to the wet paint. He didn’t care. He painted right over them.

“Pop, what are you doing?”

He didn’t look up. “What’s it look like I’m doing? I’m painting a car.”

I figured he bought the car as a second car and since he was living in a restricted community by then he could not paint it there so i asked him if I could help. “Sure can- there’sa nother brush on the seat” So WE painted the Car..I asked where he got the paint. I think he told me it came from Jack’s place—Jack had a boat once, and the hull was painted that exact color. That boat never touched water as far as I know. But the paint found a purpose.

Pop and I worked until the car was fully painted—no primer, no spray gun, just steady hands and a thick coat of boat paint drying faster than we could lay it down. It wasn’t pretty, but it was solid. You could’ve thrown a rock at the side of that car and not scratched it.

When he finished, he turned to me and said, “Mike, it’s your car. I bought this for you.”

Just like the bicycle.

Only a lot bigger.

Epilogue: The Father’s House

I’ve come to believe that one of the greatest gifts God gives us is family we can trust—and memories we can return to. The kind that remind us what safety felt like before we even had words for it. When you’re little and afraid of the dark, or trying to understand the world, God often shows Himself in the steady voices and patient hands of the people who raised you.

Years later, after I got saved, I started sharing the gospel—recording cassette tapes and mailing them to my grandparents. They listened to me the way I used to listen to them. And, in time, they both got saved. Then my mom did too. And maybe, Lord willing, my dad. God works like that. Through steady love. Through generations.

That’s what I try to tell my girls: When it’s time to choose someone to walk beside you, pay attention. Watch how he treats his mother. Ask to see the family album. Sit down, turn the pages, and ask for the stories. And most of all, find out if he loves Jesus.

Because in the end, all the patchwork cars, nightlights, and cherry pipe tobacco fade—but the love of Christ doesn’t. And if a man carries that love, you’ll feel it. Even in the dark.