One Man's Treasure: Michael Zinman and His Trove of Early American Republic Manuscripts

One of my favorite literary tropes has to be that of the eccentric millionaire, who for some reason focuses his personal spending on some particular set of objects, manuscripts, or what have you. Those of us in the Nonprofit Management Class contributing to the Philly History Project were assigned two readings this week that both discussed this kind of person.

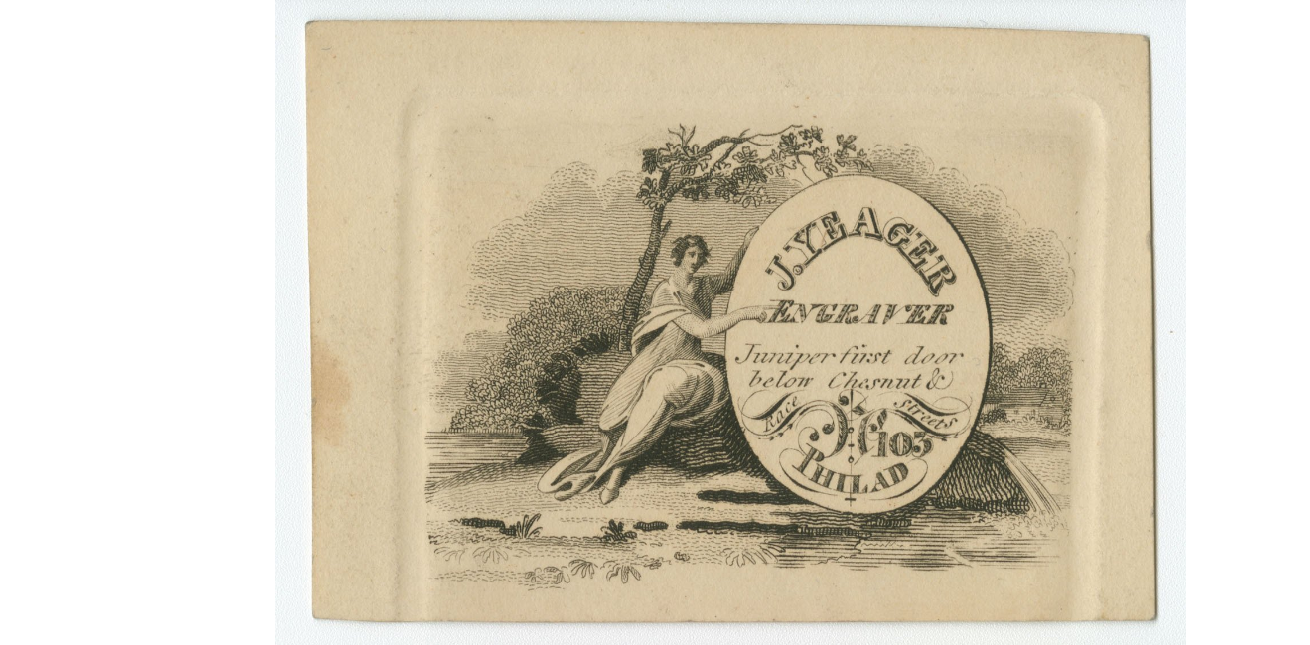

One example of the prints Zinman collected and eventually entrusted to the Library Company in 2000, courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia. http://librarycompany.org/

Michael Zinman is a New York businessman who has made his money selling heavy machinery, like natural gas turbines. At the same time, however, I would say what defines him is his fascination with Early American (pre-1800) imprints and manuscripts. Zinman first started collecting these prints decades ago, but he honed his focus, and voracious appetite for these books in the 1980s. When he started focusing on these literary materials in the 1980s, they were abundant enough in the market that there came a time when he could just trade certain manuscripts of which he had multiples for others which he had not yet acquired.

Ah yes, sweet 90's nostalgia

As a shameless millennial, this of course reminded me of the Pokemon/Yugioh card trading which was so popular when I was growing up. My younger brother actually had an entire binder full of Yugioh cards by his early teen years which he ultimately gave to a friend after he lost interest. In retrospect, he probably could have made some decent money of that collection had he sold them instead. This personal tangent aside, I am convinced that we as humans are prone to collect certain things that resonate with us. For my brother it was Yugioh cards, and for Zinman, his fancy is Early American manuscripts.

In February 2000, Zinman sold his vast collection (in the tens of thousands) of books, newspapers, leaflets, and other written materials to The Library Company in Philadelphia. The Zinman Collection at The Library Company, in conjunction with the collection of Early American manuscripts at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania was subsequently second in size only to the American Antiquities Society’s collection. For reference, this joint collection between The Library Company and HSP holds 16,750 imprints from the Early Republic.

A Google StreetView image of The Library Company of Philadelphia's at 1314 Locust Street.

Now, the theme for this week’s readings is “Institution Building with Challenging Collectors.” Accessioning from collectors like Zinman strikes me as an exercise in bartering. There comes with such accessions questions of original order for those who have to process the incoming content. This made me wonder what kind of order Zinman kept his imprints in when he shipped them to the Library Company in 2000.

My biggest question from this for you this week, dear reader, is if you had a consistent and sizeable income, what would you use it to collect? Zinman worked in selling heavy machinery, but used his earnings to fund his true passion of collecting manuscripts. What would you collect, and why? What issues do you think personal collections pose for institutions who eventually accession them into their own archives?

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment is part of a graduate course at Temple University's Center for Public History and is exploring history and empowering education to endow meaning. To learn more click here.

Sources:

James Green, The Zinman Collection and the Library Company. (Philadelphia: The Library Company, 2001), pp. 27-45

James Green, "Supplementing Early American Imprints: The Extraordinary Collection of Michael Zinman," Readex Report, Vol. 5, No. 3 (September, 2010).

Mark Singer, “The Book Eater: Michael Zinman, obsessive bibliophile, and the critical mess theory of collecting.” The New Yorker, February 5, 2001, pp. 62-71.

Please elaborate. What exactly do you mean by "order." And how could keeping or changing "order" impact the way we perceive and possibly use the collection?

When I refer to "order" I refer to the archival phrase "original order," that is, how the collector originally structured his collection. Did try to structure them chronologically? Thematically? By creator? All of these factors impose different perceptions on whoever would process the collection upon its arrival, and also would impact how users would engage with them. Often we see the ways archives organize collections and simply take it at face value, but the way we organize things influences the assumptions and inferences those who would use them make. Thanks for commenting!