Love Thy Neighbor: American Nativism against German Americans in 1918

During times of war, it is not uncommon for the enemies engaged to use propaganda to defame one another. In 1918, after the United States entered into World War I, this was the case with American attitudes towards Germans. In Philadelphia, newspapers like the Philadelphia Inquirer published numerous articles about the war that dehumanized and demonized the country’s German opponents. Though these publications may have maintained support for the war effort, they also had a negative affect on American attitudes towards their German American neighbors.

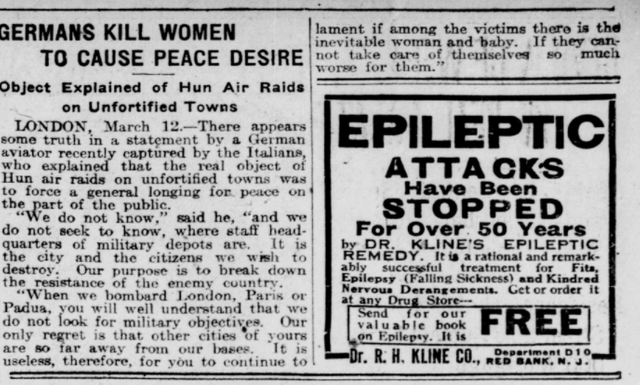

-A March 31st, 1918 article from the Philadelphia Inquirer including testimony from a captured German on their motives in bombing undefended towns. Accessed through ProQuest.

On March 31st, 1918, one article from the Philadelphia Inquirer based out of London sought to explain the true motive behind “Hun” bombings on unfortified towns. They explained that these German assaults on unfortified towns were intended to create a sense of desperation for peace talks among the Allies. These explanations came from an allegedly captured German aviator, one of whose comments reads: “Our only regret is that other cities of yours are so far away from our bases. It is useless, therefore, for you to continue to lament if among the victims there is the inevitable woman and baby. If they cannot take care of themselves so much worse for them.” This depiction of the enemy Germans as monsters who would harm women and children was hardly an isolated theme either.

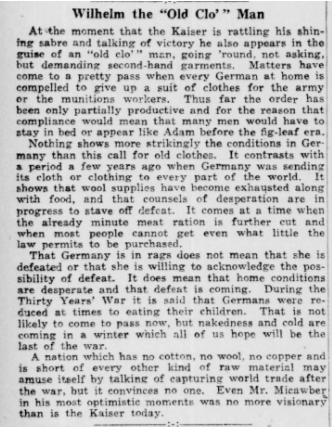

- An August 3rd, 1918 article from the Philadelphia Inquirer describing, among other things, the Germans' alleged history of cannibalism in times of war. Accessed through ProQuest.

Another article in the Philadelphia Inquirer, dated August 3rd, portrays the “Huns” as feral men who would resort to cannibalism should the need arise. The author wrote: “That Germany is in rags does not mean that she is defeated or that she is willing to acknowledge the possibility of defeat. . . . During the Thirty Years’ War it is said that Germans were reduced at times to eating their children.” This suggested to readers, already gripped by the furor of war, that their enemies were little more than savages who would devour their own children before admitting defeat.

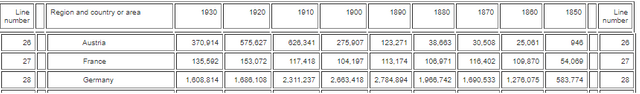

What these articles do not express, however, is that in 1918, German Americans were the largest non-English speaking population in the United States. In 1910, for example, roughly nine percent of the American population had been born in Germany or was of German parentage. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 1910 this added up to 2,311,237 citizens who were either born in Germany or had German parentage and 626,341 who were born in Austria or had Austrian parentage. These articles, which demonized a military adversary, also succeeded in the demonization of the largest immigrant population in the United States. So what impact did this have here in America?

- Excerpt from a table of U.S. Census information presenting the numbers of German and Austrian born/descended Americans between 1850 and 1930. Accessed from the United States Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0029/tab04.html.

For one thing, employment became complicated for people of German-speaking origins. In an article from the Philadelphia Inquirer, the chairman of the local Y.M.C.A. board described the kinds of men his organization sought for service overseas. After specifying that the men applying should not be of drafting age, who should be of athletic build, and so forth, Chairman Bok explicitly stated “No one … who is of German or Austrian parentage. The only necessary qualification is that men shall be honest, clean and decent in thought and habit.” This implied, of course, that any applicant of Germanic heritage was inherently dishonest and indecent.

Perhaps worse than being undesirable for employment, German Americans were expected to disavow their culture and language. In the final report from a German American who sought to purchase a liberty loan to support the war effort, he also attested to his experience as an advocate for teaching German in schools. He described how, “a prominent citizen of Pennsylvania shook his fist in my face and told me if I advocated allowing children to learn German in public schools, he would denounce me for treason.” This prominent citizen threatened this during a time where the Espionage Act and Sedition Act were fully enforced.

The notion of having to suppress one’s own identity, one’s culture, and even having to denounce one’s own language seems like it should be one long since placed on the shelves of history. Yet this remains a severe reality in American life a century later. With a president leaving the fates of 800,000 children in the balance for their Spanish-speaking heritage, and a Congressional body that largely refuses to help them; a president that has referred to African nations and Haitian immigrants in vulgar language; and with raids that separate parents from children, perhaps forever, these toxic nativist beliefs are alive and well outside of wartime, and more severely, they are backed by action. I share this post with you all today to show that, even if history is not cyclical, its lessons may not be ignored.

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment is part of a graduate course at Temple University's Center for Public History and is exploring history and empowering education to endow meaning. To learn more click here.

Sources:

"Germans Kill Women to Cause Peace Desire: Object Explained of Hun Air Raids on Unfortified Towns," Philadelphia Inquirer, March 31, 1918.

"Bok Describes Men Needed by Y.M.C.A.," Philadelphia Inquirer, July 31, 1918.

"Wilhelm the "Old Clo'" Man," Philadelphia Inquirer, August 3, 1918.

Katja Wüstenbecker, "German-Americans During World War I," Immigrant Entrepreneurship: German-American Business Biographies, September 24, 2014. https://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entry.php?rec=214. (Accessed 2/5/18).

U.S. Bureau of the Census, "Region and Country or Area of Birth of the Foreign-Born Population, With Geographic Detail Shown in Decennial Census Publications of 1930 or Earlier: 1850 to 1930 and 1960 to 1990," U.S. Bureau of the Census, released March 9, 1999. https://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0029/tab04.html. (Accessed 2/5/18).

German Society of Pennsylvania Library, Max Heinrici Collection, MS. Coll. 46, Folder 10.

Anti-German sentiment in the US and in Philadelphia rose and fell with different issues over the centuries. German-speaking immigrants were the first Caucasians to protest slavery in 1688. The introduction and daily consumption of lager beer more than a century a a half later fed other negative stereotypes. And there was much, much more.

Last semester when we were aboard the Olympia, I asked Kevin about this helmet. Apparently, the USMC used these helmets during the late 19th century to show their admiration for Prussian militarism. Obviously, those attitudes changed during WWI, and they adopted new head gear.

Fascinating! I didn't notice the helmet at all. I wonder what their new headgear evoked? Was it based on some other country's uniforms?

Thanks for this post, Derek. I've always found it interesting how it seems cannibalism was a go-to insult one-hundred years ago. I suppose after the well-documented famines of the twentieth century, such comments faded away as people saw the suffering that hunger brings.