What I Learned in School and the Battle for Western Civilization, Part 3

This is the third in a series of articles titled What I Learned in School: The Battle for Western Civilization. The previous article focused on how I deprogrammed myself from my schooling; training myself to approach new subjects from a beginner’s mind and how to explore topics I was unfamiliar with.

One of my most hated and unfamiliar topics was history. History frustrated me because it was like reading a grab-bag of vaguely related facts and being forced to memorize names and dates that could simply be looked up in common reference material. I was never taught any way of extracting patterns and useful understanding from the subject. Years after graduating college, I ran into a by Carroll Quigley titled The Evolution of Civilizations that provided a brilliant look into how to practically approach history. Quigley presents what I’m referring to as the “iron” rule of history: the institutionalization of instruments. This article will detail and explore this rule and its importance.

The Iron Rule of History: Instruments and Institutions

Templar Knight (Image Source.)

As I mentioned in previous articles, in order to have a practical approach to history, we must have a scientific method for analysis. Is there a core formula of history that can be written as specific and mathematically as those in physics? No, I don’t think we can use that “pure formula” approach in history, but nevertheless we can do better than just describe one damn fact after another. We can formulate historical principles to understand these facts. From his book The Evolution of Civilizations, Quigley formulates a key historical principle: how human social organizations have a tendency to shift from being an instrument to an institution.

Okay, so what’s an instrument and an institution, in the sense to which Quigley is referring?

Because human societies have human needs, individuals within a society must develop methods to meet those needs. Whether the needs are broadly recognized as intellectual, religious, social, economic, political, or militaristic (Quigley’s categories), social organizations consisting largely of personal relationships must be developed in order to meet the needs of the society. A social organization developed to meet these needs is an instrument. For example, an army would be a militaristic instrument with the purpose of meeting the need of security. A banking and credit system would be an economic instrument to meet financial needs, a university an intellectual instrument to meet educational needs, and so on.

Actually, I don’t think I need one of these. Do you? (Image Source.)

The societal “instrument” is considered an instrument as long as it is relatively effective at accomplishing the purpose for which it arose. However, there is a remarkably consistent tendency in history: instruments will eventually become institutions. This slowly occurs as the individuals making up the instrument become more and more focused on their own needs over the purpose of the instrument. In the example of the army, which set out to provide security to the society, eventually finds itself more focused on training soldiers, moving supplies and munitions, pleasing politicians and the populace, and ensuring the paychecks and benefits of retired military personnel.

Quigley provides an excellent military example of an instrument becoming and institution in his book: cavalry. The purpose of the cavalry was mainly to provide scouting intelligence, to act as a “mop-up” attack to end a battle, and to add speed to attacks and ambushes that could not be provided by soldiers on foot. There are some estimates that humans have been riding horses for almost 4000 years, and for that length of time mounted soldiers represented one of the most powerful military assets a general could command. The Roman Empire fell partially to its inability to create its own large mounted force to counter the mounted Germanic invaders that eventually sacked Rome, and Mongols nearly conquered the entirety of Eurasia with mounted soldiers.

I’ve heard that the Mongolian horse archers used 180 pound bows. I can’t even pull back the string on an 80 pound bow. God damn. (Image Source.)

However, by the time of the advent of gunpowder, cavalry had become obsolete. By the time of the wars of Napolean in the early 19th century, it would have been obvious to any observer that a cavalry charge against infantry firearms was suicidal. The age of its glory over.

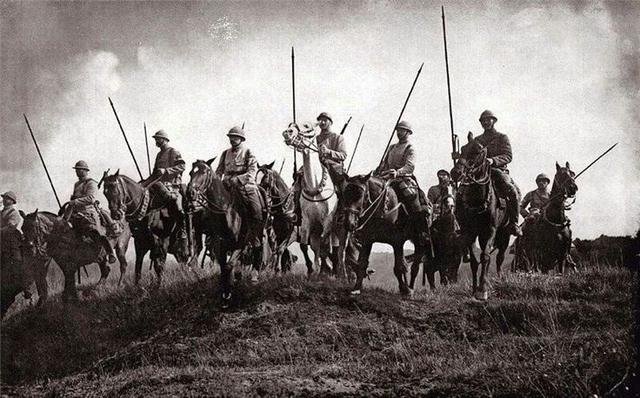

However, more than a hundred years later with the outbreak of WWI, military commanders still emphasized the importance of cavalry despite their utter uselessness if the face of machine gun fire. In fact, the cavalry was worse than useless: on all sides of the war, there were intranational battles over shipping—horses and horse fodder in many cases could take up to a quarter of shipping space which was direly needed to ship men, munitions, and other supplies. Officers dedicated to the tradition of the cavalry, claiming even to the end of the war that it was just a matter of time for a break in enemies lines to send the cavalry in and “mop-up” the enemy, fought bitterly with politicians who had recognized its obsolescence. Quigley mentions that the complications that arose from shipping horse fodder may have been one of the prime factors for Russia deteriorating during the war. The cavalry instrument had fully crystallized into a cavalry institution.

“Ready to charge into machine gun fire, Sir!” I'm sure those lancers were useful for trench warfare. Eye roll. (Image Source.)

In this example of cavalry, we can see that an institution can survive a hundred years, even in the event of its provable detriment to society: vast resources that could have been better spent to influence the outcomes of wars were put towards horses and the supplies for horses. This phenomenon of instruments eventually morphing into institutions stretches across all societal organizations. Quigley even gives a humorous account of the history of football (soccer) in British universities to emphasize all societal organizations.

In the 1870s, football was adopted on campuses as a way for undergraduates to get some exercise. Regular games led to competition between teams, which led to competitions between universities. People began to watch, and schools began to charge for games. Naturally, graduated players would be invited back to coach teams, the coaches themselves eventually becoming full-time employees of the school. Fast forward a few years and we have the first construction of the modern stadium in 1903, scouting for players to play on the team, and full-ride sports scholarships. Thus what was originally an instrument to get undergraduates who needed exercise to exercise, became an institution where the students who needed the exercise the most sat and watched the students who needed the exercise the least play football.

Something about the people needing the exercise watching the people who don’t...(Image Source.)

I don’t know if this is an accurate history of the development of football, but the story still stands as an excellent example of how even something as innocuous as a college sport can morph to accomplish the opposite of what it was intended to do.

Quigley gives three reasons to the cause of the institutionalization of instruments:

First, because an organization consists of multiple people with multiple roles, each individual is naturally focused on their role within the organization, not the overall purpose of the organization. The coach’s purpose on the football team is to win games, not to get students to exercise.

Second, humans are inclined to seek out better positions for themselves, especially with employment. Even if we assume no corruption is at play (where an individual knowingly and purposefully benefits at the expense of the organization he works for), it is natural to seek promotions, better pay, better status, etc. This force slowly shifts the focus away from the original purpose of the organization to the interests of the individuals within the organization.

Third, social conditions will change. This means if the organization doesn’t change to meet the new social conditions, the organization will become less effective at accomplishing its purpose and goals. As is easily ascertained from the first two points, most individuals within the social organization will resist this change. They become comfortable with their positions and their pay, and it is no wonder that the acceptance of new conditions that would prove their obsolescence would terrify them into rationalizing the existence of their positions at all costs.

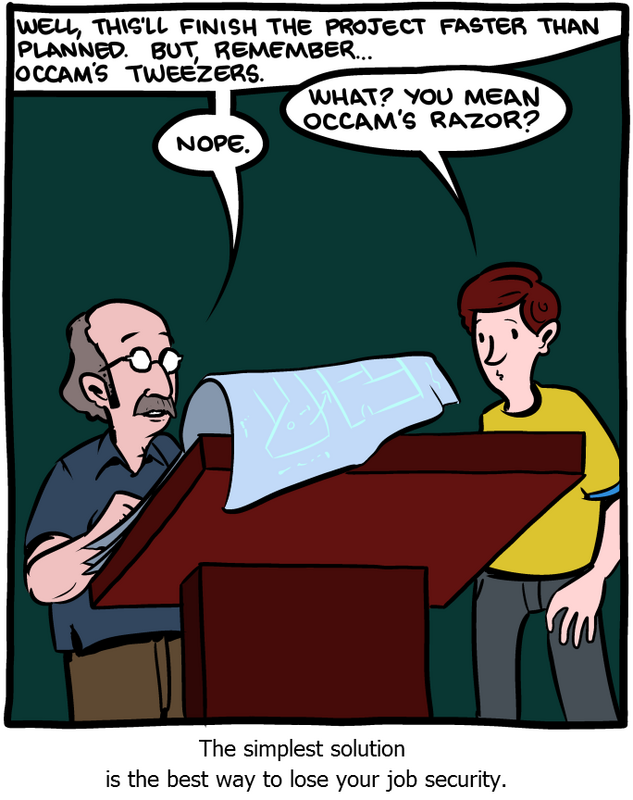

Comics from SMBC Comics. (This Comic.)

With these three points in mind, it is a little easier to understand why the cavalries of WWI, already a hundred years useless, fought to the bitter end for wartime resources, even at the potential cost of victory in the war. The instrument known as cavalry, with the specific military purpose of swift “mop-up” attacks and scouting, had become institutionalized and fought for existence even though it no longer did either of these things.

In the next article we will explore how this concept of institutionalization of instruments applies to the core economic factors that are the heartbeat of civilizations. This will allow us to understand just what is so different about Western Civilization, and why it’s worth saving. Stay tuned!

You can read the previous articles here:

Part 1, What I Learned in School.

Part 2, Deprogramming History, and Deprogramming Myself

-Dylan Lawrence Moore

@volsci

Follow, re-steem, and share. Thanks!

Follow me on Youtube!

Another fascinating read, thank you. Very interesting analogies ... really makes one think about the evolution of so many systems in society.

Congratulations! This post has been upvoted from the communal account, @minnowsupport, by CrazyRogue from the Minnow Support Project. It's a witness project run by aggroed, ausbitbank, teamsteem, theprophet0, someguy123, neoxian, followbtcnews, and netuoso. The goal is to help Steemit grow by supporting Minnows. Please find us at the Peace, Abundance, and Liberty Network (PALnet) Discord Channel. It's a completely public and open space to all members of the Steemit community who voluntarily choose to be there.

If you would like to delegate to the Minnow Support Project you can do so by clicking on the following links: 50SP, 100SP, 250SP, 500SP, 1000SP, 5000SP.

Be sure to leave at least 50SP undelegated on your account.