On Libertarianism and Pandemics

The Wēnyì (Chinese: 瘟疫; plague, pestilence, epidemic, murrain) of 2019–20 has subjected the ruling regimes of the world to a test that they have not faced in a century. City-wide lockdowns have been imposed, public spaces have been closed, quarantines have been implemented, flights have been canceled, and the resulting pressures have strained many economies close to the breaking point. The models upon which political leaders have based their decisions have been shown to be both fundamentally flawed and derailed by faulty inputs. All of the aforementioned have been analyzed and criticized by other writers at length, but what has yet to be explored in proper depth is the manner in which a libertarian social order might respond to such a challenge.1 Let us refresh ourselves on the fundamental philosophy of a libertarian reactionary order, consider the current pandemic, then apply these tenets to the issues of quarantines and pandemics.

(Reactionary) Libertarianism 101

The starting point for libertarian ethics is self-ownership; that each person has a right of exclusive control over one's physical body and full responsibility for actions committed with said control. This is demonstrated through argumentation ethics; in order to argue against self-ownership, one must exercise exclusive control of one's physical body for the purpose of communication. This results in a performative contradiction because the content of the argument is at odds with the act of making the argument. By the laws of excluded middle and non-contradiction, self-ownership must be valid because it must be either valid or invalid, and any argument that self-ownership is invalid leads to a contradiction.

The non-aggression principle is little more than a restatement of self-ownership; if each person should have exclusive control over one's physical body, then it is wrong for one person to initiate interference with another person's exclusive control of their physical body against their wishes. Private property emerges from responsibility for one's actions; one should be responsible for the improvements that one has made with the natural resources upon which one has labored, and it is impossible to own the improvements without owning the resources themselves. Personal responsibility also means that one should owe restitution for any acts of aggression that one commits against other people or their property. Every aspect of (reactionary) libertarianism that is more complicated than this arises from the following facts:

- Each person is (or, at least, necessarily has) a physical form which occupies space and requires sustenance.

- Situations may arise which put the aforementioned principles into conflict with one another.

- Human actions frequently fail to adhere to principle.

Enter Corona

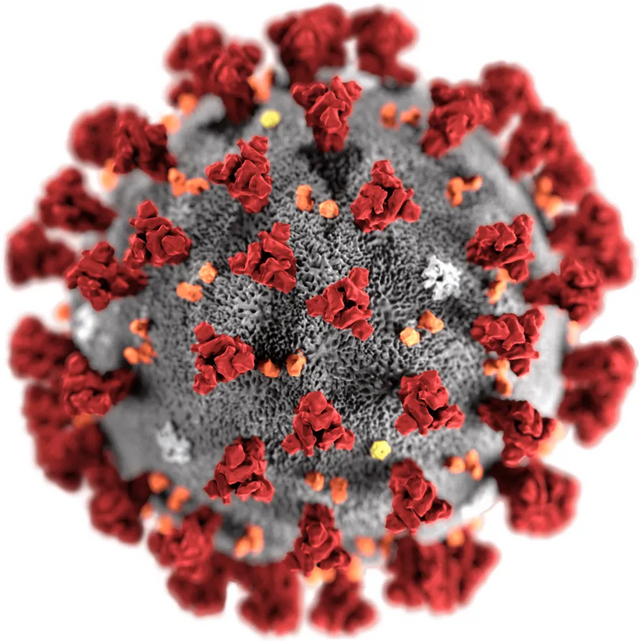

The pathogen responsible for the Wēnyì is a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) that bears resemblance to those which caused the SARS epidemic (2002–04) and MERS outbreaks (2012 Middle East, 2015 South Korea, 2018 Saudi Arabia). It is a different subspecies of the former. Four other coronavirus species (HCoV-229E, HCoV-HKU1, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-OC43) cause variants of the common cold and are less dangerous than MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2.[1] In humans, these viruses cause respiratory tract infections ranging from mild to lethal, while other mammals and birds are affected differently.[2]

Common symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 include cough, fatigue, fever, joint pain, loss of sense of smell, muscle pain, shortness of breath, and sputum production. Diarrhea, nausea, runny nose, sneezing, sore throat, and vomiting have also been observed with less frequency.[3,4,5] Less common and more severe symptoms include bluish skin, breathing difficulty, chest pain, confusion, difficulty waking, organ failure, viral pneumonia, and death.[6] Symptoms usually onset around 5–6 days after exposure, but ranges from 2–14 days.[7]

A significant minority do not develop symptoms but may still spread the disease[8,9]; the number of those infected by asymptomatic people may be as high as 40 percent.[10] The Wēnyì spreads primarily through close contact, such as through droplets spread by coughing, sneezing, or talking. It spreads more easily than influenza but not as easily as measles. People are most infectious around the time that they begin to show symptoms, but may be infectious for two days beforehand and two weeks afterward.[11] Droplets may also contaminate surfaces for up to 72 hours, which can cause infection if a person touches the surface and then touches their mucous membranes.[12] Surfaces easily are decontaminated with household disinfectants. The R0 (number of people infected by one infected person) is estimated to be 3.28 without control measures.[13] This number must be reduced below 1.0 for a given disease to fade away and no longer be an epidemic, which is the ultimate goal of control measures.

The Wēnyì began in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China on 17 November 2019[14], and was first identified in December.[6] At the time of this writing, more than 15.6 million cases have been reported across 188 countries and territories. By official counts, at least 636,000 people have died and 8.91 million people have recovered.[15] These figures give a mortality rate of 4.08 percent and a recovery rate of 57.1 percent, with 38.8 percent of cases ongoing. However, those who survive can suffer lasting damage. The virus is known to attack the central nervous system (CNS) through the brain stem, though the exact mechanism by which it invades the CNS is not yet known.[16,17] Gastrointestinal organs are vulnerable to chronic damage[18,19], as are the cardiovascular system[20] and the kidneys.[21,22]

There is not yet a standard treatment protocol for SARS-CoV-2. Vaccines are in the early stages of clinical trials, and their development is occurring on a rushed timetable.[23] On May 1, 2020, the United States gave Emergency Use Authorization for remdesivir because a study suggested it may reduce the duration of recovery.[24] Other considered medications include hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, zinc[25], and tocilizumab. Recommended countermeasures include avoiding touching one's face, covering coughs and sneezes, frequent hand washing, physical distancing from others, and the use of face coverings.

Read the entire article at ZerothPosition.com

Footnotes

- A notable exception is the matter of healthcare in a libertarian social order, which has been explored elsewhere.

- Fehr, A.R.; Perlman, S. (2015). Maier, H.J.; Bickerton, E.; Britton, P. (eds.). “Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis”. Methods in Molecular Biology. Springer. 1282: 1–23.

- Corman, V.M.; Muth, D.; Niemeyer, D.; Drosten, C. (2018). “Hosts and Sources of Endemic Human Coronaviruses”. Advances in Virus Research. 100: 163–88.

- Wei, Xiao-Shan; Wang, Xuan; Niu, Yi-Ran; Ye, Lin-Lin; Peng, Wen-Bei; Wang, Zi-Hao; Yang, Wei-Bing; Yang, Bo-Han; Zhang, Jian-Chu; Ma, Wan-Li; Wang, Xiao-Rong; Zhou, Qiong (2020, Feb. 26). “Clinical Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 Infected Pneumonia with Diarrhea”.

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; et al. (Feb. 2020). “Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China”. Lancet. 395 (10223): 497–506.

- Lai, Chih-Cheng; Shih, Tzu-Ping; Ko, Wen-Chien; Tang, Hung-Jen; Hsueh, Po-Ren (2020, Mar. 1). “Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): The epidemic and the challenges”. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 55 (3): 105924.

- Hui, D.S.; I. Azhar E.; Madani, T.A.; Ntoumi, F.; Kock, R.; Dar, O.; et al. (Feb. 2020). “The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health—The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China”. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 91: 264–6.

- Velavan, T.P.; Meyer, C.G. (Mar. 2020). “The COVID-19 epidemic”. Tropical Medicine & International Health. p. 278–80.

- Lai, Chich-Cheng; Liu, Yen Hung; Wang, Cheng-Yi; Wang, Ya-Hui; Hsueh, Shun-Chung; Yen, Muh-Yen; Ko, Wen-Chien; Hsueh, Po-Ren (2020, Mar. 4). “Asymptomatic carrier state, acute respiratory disease, and pneumonia due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): Facts and myths”. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology, and Infection.

- Bai, Yan; Yao, Lingsheng; Wei, Tao; Tian, Fei; Jin, Dong-Yan; Chen, Lijuan; Wang, Meiyun (2020, Feb. 21). “Presumed Asymptomatic Carrier Transmission of COVID-19”. JAMA. 323 (14): 1406.

- “Getting a handle on asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection | Scripps Research”.

- “Q&A on COVID-19”. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

- van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, et al. (Mar. 2020). “Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1”. New England Journal of Medicine.

- “Novel Coronavirus - Information for Clinicians”. Australian Government Dept of Health.

- Ma, Josephine (2020, Mar. 13). “Coronavirus: China's first confirmed Covid-19 case traced back to November 17”. South China Morning Post.

- “COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU)”. ArcGIS. Johns Hopkins University.

- Li, Y.C.; Bai, W.Z.; Hashikawa, T. (Feb. 2020). “The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients”. Journal of Medical Virology. 92 (6): 552–5.

- Baig, A.M.; Khaleeq, A.; Ali, U.; Syeda, H. (Apr. 2020). “Evidence of the COVID-19 Virus Targeting the CNS: Tissue Distribution, Host-Virus Interaction, and Proposed Neurotropic Mechanisms”. ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 11 (7): 995–8.

- Gu, J.; Han, B.; Wang, J. (May 2020). “COVID-19: Gastrointestinal Manifestations and Potential Fecal-Oral Transmission”. Gastroenterology. 158 (6): 1518–9.

- Hamming, I.; Timens, W.; Bulthuis, M.L.; Lely, A.T.; Navis, G.; van Goor, H. (June 2004). “Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis”. The Journal of Pathology. 203 (2): 631–7.

- Zheng, Y.Y.; Ma, Y.T.; Zhang, J.Y.; Xie, X. (May 2020). “COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system”. Nature Reviews. Cardiology. 17 (5): 259–60.

- Wadman, M. (Apr. 2020). “How does coronavirus kill? Clinicians trace a ferocious rampage through the body, from brain to toes”. Science.

- Sperati, C. John. “Coronavirus: Kidney Damage Caused by COVID-19”. Johns Hopkins Medicine.

- Moffitt, Mike (2020, Apr. 11).“The COVID-19 vaccine rush: Is 12 to 18 months realistic?”. SFGate.

- “Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Issues Emergency Use Authorization for Potential COVID-19 Treatment”. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 1 May 2020.

- “Hydroxychloroquine, Azithromycin, and Zinc Triple-Combo Proved to be Effective in Coronavirus Patients, Study Says”. Science Times. 12 May 2020.

- Hoppe, Hans-Hermann (2001). Democracy-The God That Failed: The Economics and Politics of Monarchy, Democracy, and Natural Order. Transaction Publishers. p. 20–1.

- Curl, Joseph (2020, May 24). “500 Doctors Tell Trump To End COVID-19 Shutdown, Warn It Will Cause More Deaths”. Daily Wire.

- Weiss, Yinon (2020, Jun. 11). “Unnecessary Lockdowns Created Social Turmoil, Global Suffering”. RealClearPolitics.

- Hanson, Robin (2020, Feb. 14). “Consider Controlled Infection”. Overcoming Bias.

- Hanson, Robin (2020, Feb. 17). “Deliberate Exposure Intuition”. Overcoming Bias.

- Coase, Ronald (1960). “The Problem of Social Cost”. Journal of Law and Economics, p. 1–44.