Do human organizations need cheaters? Why or why not?

@remlaps proposed an intriguing question of the year for people to grapple with: Do human organizations need cheaters? Why or why not?

My initial, instinctive response was "no", so I feel like I need to consider some reasons that the answer might be "yes" before locking that in.

Some institutions did require cheaters

Several months ago I read the book Seeing Like a State (posted my thoughts about that here), and one of the examples presented of the failures of top-down planning was that the managers of Soviet factories depended on having people on staff who were able to work black markets or use other under-the-table methods to keep the factories running and hitting their quotas. Their system needed these "cheaters" in order to not seize up completely. My inclination is to say that this was evidence that their system was bad, and the cheating was only "necessary" to counteract other flaws of their system, but still it indicates that the question isn't a crazy one.

Tabletop RPGs

One of my areas of interest is tabletop roleplaying games, and many people consider it necessary for GMs to selectively enforce rules, fudge dice rolls, etc., to make games fun. While these practices aren't generally called cheating I think they essentially are. Personally I don't think they're necessary, I think that those practices are in place to work around flaws in the game designs of those systems (which happen to dominate the hobby in terms of popularity), and that it ought to be possible to make fun roleplaying games which don't require such a tenuous relationship to rules and game design, but I can't point to a huge track record of success for RPGs that take rules seriously. So I can't completely dismiss the idea that these practices are important, even if I have the strong suspicion that they're not.

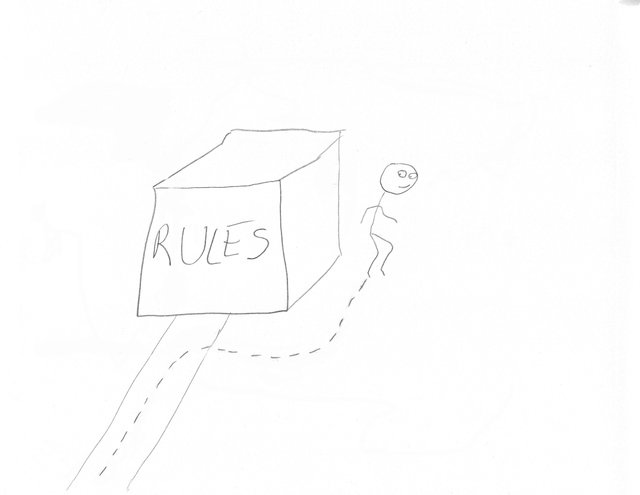

Rules vs Creativity

Many people view rules and constraints as the enemy of creativity, that in order to be creative you have to be able to color outside the lines. Again I think that goes too far, but I think there's an element of truth to it. I think creativity requires exploration, and being able to reconsider whether particular rules work can be necessary. But I think the way to do that is to keep people from being too rigidly locked in to institutions. You don't need to break the rules of haiku with your poetry because you have the option of writing non-haiku poems (and having that option can make accepting the rules of a particular form more meaningful when you do it).

Would you wish it was impossible to cheat?

If some sort of genie offered to magically make it impossible for humans to cheat, would you take him up on the offer? That strikes me as extremely dystopian. While I tend to follow the rules, it feels like I would be losing something important about being a human if I wasn't able to break them.

Civil Disobedience

Many people consider the US Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 60s to be a major cultural achievement, and one of the mechanisms that people like Martin Luther King Jr. used in that effort was "civil disobedience", where they would do things that were against unjust laws as protest against those laws. Were they "cheating"? I think it makes more sense to think of what they were doing in a broader context: the normal way that laws and norms work is that when something is against the law there's a strong norm against doing it, so you voluntarily comply with it. But they chose to look at those laws as "if you do activity X you will be punished with consequence Y". By stepping away from voluntary compliance and exposing themselves to punishment Y they challenged society to see if it could really stomach the social costs of dishing out that punishment merely to keep certain people from doing activity X. Because most people weren't very committed to racially discriminatory laws that civil disobedience was an effective form of protest. So I think of it as a practice of radical compliance rather than something on the "cheating" spectrum. Still, they were violating the rules of the time, and most people today think it was necessary for them to do so.

A lot of robust systems have exceptions or other "release valves"

If we look at the law, in the American system we often have exceptions or other mechanisms to allow getting around a hyper-strict reading of rules. For example, generally we outlaw homicide but you're not guilty of the crime if you do it in self-defense. And while the president's pardon power can be used in sketchy ways, it does seem like it's good to have a way to counteract things when the machinery of justice produces an unjust result in particular cases. We wouldn't have these mechanisms if excess strictness were never a problem.

So what's my conclusion?

I don't think human organizations need cheaters and cheating to work, but it seems that allowing for the possibility of cheating may be necessary. People creating institutions may be less likely to make them overly constraining and incompatible with human flourishing if they consider that cheating may be possible -- it can work like a limiting factor if they have to build things such that people will want to use them the right way. The presence of cheating may also function as a signal that there are problems in institutions -- you don't have to condone any particular choice to break a rule, but if a rule is getting consistently broken then there may be a problem with it (the "fix" that cheaters are using may not be the right one, but most people don't cheat for no reason, there probably is some problem somewhere that they're trying to address).

Thanks for the post! I think this is turning out to be a fun question.

Probably true, though I wouldn't be surprised if many of those flaws arose from cheating by the people closer to the top of the food chain. In many cases, I think that the most active cheaters might be the ones who come to occupy central positions in an organization. This also applies to the point about Civil Disobedience. For example, with "Jim Crow", I think there's a case to be made that the people who instituted the laws were also cheaters.

I'm especially glad that you included this point:

I was having similar thoughts when I was thinking about it last week, but I forgot to include it in today's post, and I didn't get it to this level of clarity. Just the possibility of cheating definitely changes the decision landscape. I like the way you expressed that point.