Durability of Plastics

Plastic is incredibly strong, and can be molded into a mind

boggling array of stuff.But that strength also makes plastic

stick around long after we actually need it, because unlike

most materials, it simply doesn't ever fully break down.

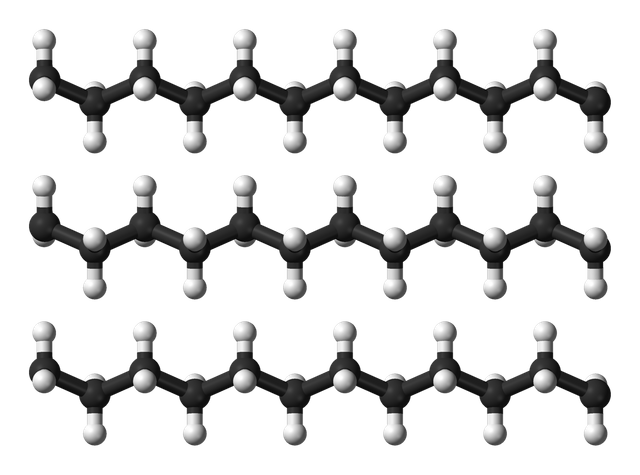

Each type of plastic is made of one chemical unit, such as

ethylene, repeated thousands of times over in long, noodle

like strands,which is why plastics’ names all start with“poly,”

the Greek word for “many.” Quadrillions of those strands get

tangled together like cooked pasta to form everything from

saran wrap to space shuttle sheathing.

source:http://www.ttfihc.com/Products/Petrochemical/Polyethylene-PE

Over time, forces like heat and tension can separate the

tangled strands of plastic from each other, causing big pieces

of plastic to break into smaller ones.But the individual strands

themselves are glued together by thousands of carbon-carbon

bonds, which are among the strongest types of chemical

linkages: neither normal amounts of heat and pressure, nor

the other usual destructive forces, can break them.So while

large bits of plastic break apart into small bits, those small

bits never really disappear.So scientists are noodling around

for a way to create less permanent plastics.

source:https://www.rushhourdaily.com/humans-produced-9-billion-tons-plastic-less-70-years/

New versions, such as polylactide, are still made up of

repeating chemical units, but instead of those everlasting

carbon-carbon bonds,the chains are held together by different

types of links, like carbon-oxygen bonds, which can be

easily cut even by water and the resulting bits can ultimately

be digested by bacteria.So after a few dozen years out in the world

or just a few months in the right processing facility these new

plastics can degrade completely into just carbon dioxide and water.

But so far, there are some drawbacks: polylactide,for example,

is more expensive than traditional plastics, and the carbon oxygen

bonds that make it degradable also give it a fairly low softening

point, making it not so practical for some uses.

So, we still haven't cooked up the perfect plastic yet, but scientists

are excited about the pasta-bilities.

References:

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/358/6365/872

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.7b10173

http://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/10/9/3722

http://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/16/1/564

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/358/6365/868