Diagnosing Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP) - Diane D. Addie

(This article is written for veterinary surgeons and reading it counts for 5 minutes continuing education or 15 mins if you also watch the embedded film.)

"A wrong diagnosis can be far more devastating than no diagnosis."

Dr Mike Willard

"More cats have died of FIP tests than have died of the disease."

Dr Niels Pedersen

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is a disease predominantly affecting young pedigree (purebred) kittens and cats. However, any age of cat can be affected. In most cases, FIP is fatal.

An erroneous diagnosis of FIP can be tragically fatal: with guardians opting to euthanase their pet to avoid suffering, or because an inappropriate therapy is given, thus the life of the pet is unnecessarily wasted.

The cause of FIP is infection with feline coronavirus (FCoV), although most FCoV infections do not have any serious consequences: most infected cats have subclinical infection, or a bout of diarrhoea.

A small percentage of cats mounts a deleterious immune response to FCoV: clinical signs form a spectrum from very acute severe infection with destruction of many blood vessels and leakage of plasma into body cavities – this is known as effusive, or wet, FIP – and death within days to weeks. (See the animation below.)

In dry or non-effusive FIP, on the other hand, the progress is slower, the number of blood vessels damaged is fewer, and a chronic immune response is a pyogranuloma formation as the body attempts to wall off the infection. Non-effusive FIP is much more difficult to diagnose than effusive FIP (and will be the subject of a later article).

In the first edition of my book for cat guardians, Feline Infectious Peritonitis and Coronavirus, I made the statement that 80% of cats diagnosed with FIP turn out to have some other – often treatable – disease.

My statement was based on having had a summer student telephone veterinary surgeons who had submitted samples to our diagnostic laboratory at the University of Glasgow Veterinary School, backed up by my personal experience of getting to the correct diagnosis in cases submitted to me for second opinion.

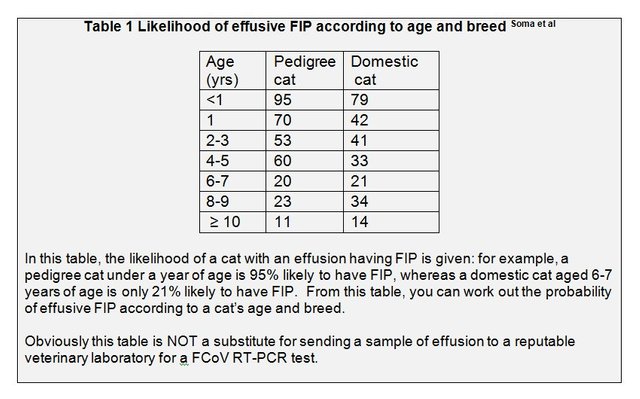

Various recent publications have enabled me to refine my 80% figure considerably. While 80% remains true for non-effusive FIP, recent research has shown that the probability that a cat really has effusive (wet) FIP varies with the cat’s age and breed.

The probability that the effusion IS caused by FIP varies with the age and breed of the cat: between 5% and 89% of cats with effusions suffer from some other condition.

Effusive FIP is much more easy to diagnose than non-effusive FIP. The legendary Italian veterinary pathologist, Dr Saverio Paltrinieri, published a paper in which 79 of 110 cats with effusions (72%) were diagnosed as having wet FIP, in the other 31 cats, the effusions were due to diseases other than FIP.

Thus a correct diagnosis was more likely to be obtained in effusive FIP compared with only around 20% (or less Jeffery et al, 2012) correct diagnoses of non-effusive FIP.

Recent research indicates that a positive FCoV RT-PCR test on an effusion is 100% diagnostic of FIP. [Doenges et al; Felten et al; Longstaff et al.] In 2013, Dr Soma and his colleagues published results of FCoV RT-PCR tests on an enormous number of effusions sent to his laboratory in Japan: these results showed that the percentage of effusions positive by FCoV RT-PCR varied with the cat’s breed and age, see table 1 which I have adapted from the graph published in Dr Soma’s paper.

Up to the age of 4-5 years, purebred cats were more likely to be positive than domestic cats, and after 6 years of age the converse became true (possibly because the domestic cats have experienced exposure to FCoV in a rescue or boarding cattery).

The percentage of effusions positive for FCoV decreased with the age of the cat: from 95% of 139 effusions from pedigree cats up to one year old, to only 11 % of effusions from pedigree cats of 10 years of age or older.

A positive reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction test on the effusion is usually diagnostic of effusive FIP: but a negative result does not necessarily rule out FIP

Since the advent of reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing becoming commercially available in many countries, diagnosis of effusive FIP has become relatively straightforward: have FCoV RT-PCR tested on the effusion!

Unless the test has poor specificity (e.g. the primers for RT-PCR for a FCoV messenger RNA RT-PCR Simons et al, 2005 also recognised some human DNA) then a positive result will be confirmation that the cat has effusive FIP, [Doenges et al; Felten et al; Longstaff et al] especially if a quantitative RT-PCR was used and a large amount of virus detected.

However, at time of writing, no paper has been published comparing the sensitivities of the various different commercially available FCoV RT-PCR tests: thus a negative test may not be able to rule out FIP.

Since FCoV is an RNA virus, it is highly subject to mutations, which mean that designing primers and probes for RT-PCRs can be challenging: a conserved region of the genome should be chosen. Veterinary surgeons should find out which RT-PCR their reference laboratory uses and try to choose a test which has been published in peer-reviewed literature: a list of laboratory tests this author trusts is given towards the end of this article.

Sending an effusion to a veterinary laboratory for FCoV RT-PCR

Only a small amount of effusion is required for RT-PCR testing: 1ml in a plain tube will certainly give enough for a laboratory to come up with a result.

Although FCoV is an RNA virus, and RNA is quite fragile, in fact when it is within a biological sample, such as an effusion, or faeces, it is remarkably robust, and can be sent in ordinary mail, without ice, without loss of a signal, for up to 3 weeks.

If using the University of Glasgow Veterinary Diagnostic Services laboratory it is worth taking advantage of the amazing cytologists who also work there, and who can often give you a diagnosis for samples which are negative, so include an air dried smear of the effusion, and some effusion in an EDTA tube.

Recommended laboratories for getting a FCoV RT-PCR test

France, Spain: Scanelis Laboratory: http://www.scanelis.com

Italy: Department of Public Health and Animal Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Bari, Italy.

Japan: Dr Soma’s Laboratory: Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, Marupi Lifetech Co. Ltd., 103 Fushiocho, Ikeda, Osaka 563-0011, Japan.

UK: Veterinary Diagnostic Services, University of Glasgow Veterinary School (we receive samples from all over the world): http://www.gla.ac.uk/schools/vet/cad/submitasample/

USA: Idexx: ask for the regular FCoV RT-PCR, not the special FIP RT-PCR which is not sensitive enough. Other veterinary laboratories are not recommended..

If you found this article useful, please give it your vote and become a follower of my articles @catvirus.

For more information on FIP diagnosis and treatment; for free continuing professional development, (CPD, continuing education, CE); or to buy the ebook “FIP and Coronavirus” visit www.catvirus.com The book is also available from Amazon.

References

Doenges SJ, Weber K, Dorsch R, Fux R, Hartmann K. 2016 Comparison of real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of peripheral blood mononuclear cells, serum and cell-free body cavity effusion for the diagnosis of feline infectious peritonitis. J Feline Med Surg. [Epub ahead of print]

Felten S, Weider K, Doenges S, Gruendl S, Matiasek K, Hermanns W, Mueller E, Matiasek L, Fischer A, Weber K, Hirschberger J, Wess G, Hartmann K. 2015 Detection of feline coronavirus spike gene mutations as a tool to diagnose feline infectious peritonitis. J Feline Med Surg. [Epub ahead of print]

Jeffery U, Deitz K, Hostetter S. 2012 Positive predictive value of albumin: globulin ratio for feline infectious peritonitis in a mid-western referral hospital population. J Feline Med Surg. 14(12):903-5.

Longstaff L, Porter E, Crossley VJ, Hayhow SE, Helps CR, Tasker S. 2016 Feline coronavirus quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction on effusion samples in cats with and without feline infectious peritonitis J Feline Med Surg. [Epub ahead of print]

Paltrinieri S, Parodi MC, Cammarata G. 1999 In vivo diagnosis of feline infectious peritonitis by comparison of protein content, cytology, and direct immunofluorescence test on peritoneal and pleural effusions. J Vet Diagn Invest. 11(4):358-61.

Simons FA, Vennema H, Rofina JE, Pol JM, Horzinek MC, Rottier PJ, Egberink HF. 2005 A mRNA PCR for the diagnosis of feline infectious peritonitis. J Virol Methods. 124(1-2):111-6.

Soma T, Wada M, Taharaguchi S, Tajima T. 2013 Detection of ascitic feline coronavirus RNA from cats with clinically suspected feline infectious peritonitis. J Vet Med Sci. 75(10):1389-92