The Unsettling of Appalachia: Identity, Activism, and Appalachian Consciousness in Conversation with S-Town (Originally published in The Activist History Review, June 22, 2017)

This is a repost of an article I wrote last year for The Activist History Review (originally published June 22nd, 2017). Though dated, it is still a relevant subject, and one that is very near and dear to my heart. I will continue to create new content on Appalachian culture and identity in the days and months to come. For now, enjoy the first fruits of my entree into the writing about the issues of my homeland. Let's continue the conversation.

The link to the original published article can be found here: https://activisthistory.com/2017/06/22/the-unsettling-of-appalachia-identity-activism-and-appalachian-consciousness-as-filtered-through-s-town/

“Because they want to be thought of as a rich nation, they are very ashamed of this place that has come to represent poverty, even though poverty exists all over the country, and exists as much in urban areas as it does in rural, if not more.”

~Eastern Kentucky author, Silas House, on mainstream America’s view of Appalachia.

Appalachia.

Say it out loud, correctly: App-uh-latch-uh.

It has a beautiful ring to it, doesn’t it? It rings like wind chimes blowing on the porch in a gentle breeze on a sunny summer afternoon. Like rainwater pouring in rivulets down a coal deposit. Like the twang of cast-iron cookware, Pentecostal cymbals, or a “thank-ye”, “bless-ye”, or “see ye tomorrey”—the beauty of Appalachia is raw, resonant, and resilient.

The severe, rugged landscape of the Appalachian region has captured the minds of our great voices, whether they be writers and poets, like Silas House and Wendell Berry, or sociologists, like Harry S. Caudill. Their writings encapsulate the conflicted identity of the Appalachian people: the eternal struggle between resistance to change, and the desire for it, that has shaped the region for decades.

Main Street in Hyden, Kentucky, the author’s hometown. Photo courtesy of the City of Hyden.

Main Street in Hyden, Kentucky, the author’s hometown. Photo courtesy of the City of Hyden.

As native sons, I appreciate their efforts at attempting to deconstruct the Appalachian collective soul (even if Harry S. Caudill was a eugenics advocate who thought that the sterilization of the undesirable genetic stock of Appalachian people was necessary for the salvation of the region). Indeed, it’s harder to write about Appalachia if you’re from there. Not that there is any lack of inspiration to be drawn from the natural landscape, the vivacious and colorful characters who dwell in the hills and hollers with names like hell-for-certain, owl’s nest, coon creek, cutshin creek, and other toponyms whose etymological history is the subject of much debate, lore, and legend (though I can tell you some stories).

Appalachia is a region too politicized to romanticize. Though the region could definitely use some romance.

If you’re not from here, it’s much easier to write about Appalachia these days. In certain circles of the (mostly) left-leaning American intelligentsia, it has become something of a control group, a barometer against which social progress can be measured in other areas of the country. It’s not difficult to understand why. Appalachia is a veritable mine of black gold—clickbait for any virtue-signaling, progressive political crusade of choice. Want to talk poverty? Check. Want to talk about environmentalism, fossil fuels, and all related issues? Check. Whiteness? Check. Bigotry, religious fundamentalism, and homophobia? Check, Check, Check. Poor health(care), a poor educational system, and a general dearth of opportunity? Yep, we’ve got it all in Appalachia—the “White Ghetto,” as the National Review flatteringly styled us, or, as the New York Times recently described us, the “Smudge of the country.” A catchall and case-study for nearly every social ill of the modern world, are we as Appalachians so reviled because we represent the cause, or the symptoms, of the utter failure of the neoliberal economic status quo of the past century?

This question could be debated ‘til the cows come home. However, another question is more pressing for the people of my beautiful but troubled region. Why, in spite of our radical history of labor activism, in spite of the war on poverty, the war on drugs, and the pipe dreams of economic pipelines of cash promised by President Obama, and the promised revival of the coal industry by President Trump, are we still waiting for things to get better?

Panoramic view of the landscape of Leslie County, Kentucky, from the rolling mountains behind the author’s house. Photo courtesy of the author.

Panoramic view of the landscape of Leslie County, Kentucky, from the rolling mountains behind the author’s house. Photo courtesy of the author.

The short answer is that, like John B. McLemore of S-Town fame, Appalachia, in failing to create a modern identity for itself that reflects the current reality of the region, has ceased to become a meaningful unity. This lack of a strong identity has left our communities broken, our citizens alienated and powerless as participants in much of the current political discourse, and thus even more vulnerable to the myriad social ills of the region.

To continue on this point, one of the things that struck me the most about John B. McLemore is the question of his identity that is explored throughout the podcast. As we discover who John is, we discover a portrait, or perhaps a caricature, of a conflicted, brilliant man. In recent discussions about contemporary Appalachian artwork, I, along with several of my other Appalachian friends, have come to realize the inherent identity conflict at the heart of contemporary Appalachian culture.

In a sense, we are sheltered by the mountains—hidden away from the outside world. We seem to retain an untouchedness (an innocence, or purity by virtue of growing up outside of suburbia or urban America), while in fact we share many of the social ills of city life—prescription drug, methamphetamine, and alcohol abuse being chief among them. With few opportunities, a strong culture of individualism, and deep roots, for most people, the options are clear: stay or go. Notice I said options, as this dilemma, for many people, is oftentimes not a choice at all.

Each path, of course, is fraught with its own perils, and unique in its own rewards.

Locals congregating in front of the author’s grandfather’s store, Sparks Trading Post in Buckhorn, Kentucky, which has been family owned and operated since 1902. Photo courtesy of the author.

My own hometown of Hyden, Kentucky, bears more than a passing resemblance to Woodstock, also known as Shittown, Bibb County, Alabama. We are in many ways a dying town born of the American coal boom, with an admittedly beautiful, rich cultural heritage of the south-central Appalachian mountains—a culture that is slowly being strangled by economic stagnation, epidemic levels of opioid abuse, religious fundamentalism, and with that, the twin ills of fatalism and resignation.

As mountain people, musicians, pioneers, tobacco growers, coal-miners, loggers, teachers, and medical professionals, our sense of identity has always been linked to our trade and our contribution to the community. It is no hyperbole to state that the economic stagnation of Appalachia that came with the collapse of the coal industry was, in many ways, the death rattle of not only our economy, but also our identity. Any Appalachian will tell you that while mining coal is a trade, being a coal miner is an identity—one of the common threads that runs throughout nearly every family in the Appalachian mountains (mine included; my great grandfather was a coal miner.) This identity is what lives deep in the collective soul of Appalachia, while the industry itself continues to decline. Some blame the policies of the Obama administration for the death of American coal, whereas some blame the increased investment in clean energy policies.

The truth, however, is simpler: the automation of coal extraction methods and the movement towards green energy have made most coal mining jobs in America obsolete. President Trump has not made good on his promises to the coal mining industry, with only about 1,000 jobs added to the coal industry since October of 2016. In a move that likely had John B. McLemore rolling in his grave, President Trump has, however, negotiated to sell American coal to China (a country much more reliant on coal and other fossil fuels than the US), which has began rejecting its usual shipments of coal from North Korea in light of recent geopolitical rumblings on the peninsula. Though it is still too early to see how the coal industry will fare under the Trump Presidency, what is clear, as John Oliver recently observed, is that Trump’s policy towards coal seems to invariably benefit coal industry moguls rather than coal miners themselves. Of course, the environment itself will be the largest casualty of such an energy policy. Any Appalachian can tell you that the interests of coal miners, their families, and coal industry tycoons do not always overlap, nor work together for mutual benefit. One only has to look at the current job numbers and the history of coal mining in America.

While the evils of big coal in the forms of black-lung, mountaintop removal, and oppressive, authoritarian monopolies that robbed many coal families of all they had have, to a greater or lesser extent, entered the public consciousness of Appalachia, what has changed is the radical way in which we have historically responded to such gross acts of oppression.

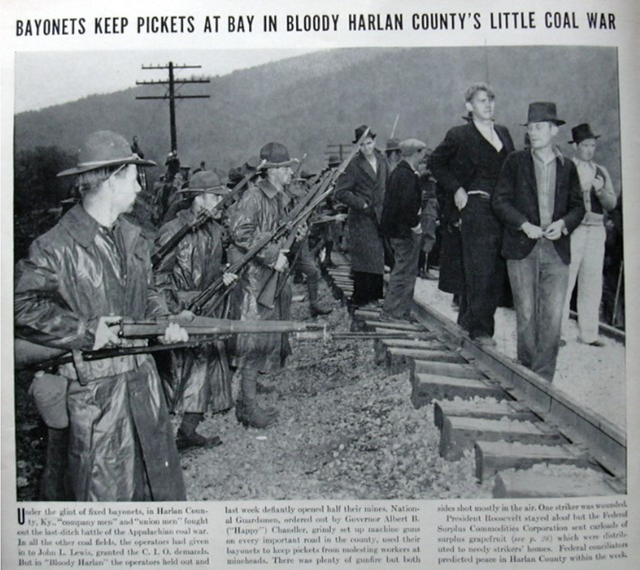

“Bayonets Keep Pickets at Bay in Bloody Harlan County’s Little Coal War,” Life Magazine, May 29, 1939, p. 26.

To those who still have family members who remember the left-wing, labor union culture of Appalachia’s United Mine Workers of America, the “Bloody” Harlan County wars of the 1930s, and further strike activity in the 70s, contemporary Appalachia must seem tame by comparison. History has shown that we Appalachians have the tenacity and the ferocity to demand accountability from forces, be they corporate or federal, that seek to oppress us. What we are missing, what keeps us from fighting back these days, is our inability to reclaim our identity as contemporary Appalachians—a group of Americans whose isolation, drug-epidemic, religiosity, economic depression, and lack of government investment have contributed to our current sad state of affairs. It would do us well to be informed by our militant, organized activist past in addressing our current social problems.

The Hurricane Creek Mine Disaster Memorial in Hyden commemorates the 38 miners who were killed in a mining disaster on December 30, 1970—the worst of its kind in U.S. history. Photo courtesy of the City of Hyden.

So what is to be done? A new modern Appalachian identity movement needs to shape itself according to the political and social needs of modern Appalachians. We need to demand accountability not only from the current federal government, but from leftists who still see it as acceptable to shame Appalachia by equating it with white supremacy and backwardness. We Appalachian progressives need to hold our progressive peers across the country accountable, and to incorporate the Appalachian experience more truthfully into current political discourse. I am hopeful that this can be done, as I am seeing many of the young twenty-something Appalachians that I have grown up with powerfully expanding the collective consciousness of the Appalachian experience through film, the fine arts, and literature. All of these cultural products present pieces of the contemporary Appalachian identity and discussions which help to further the dialogue. These are small steps, yes, but as Eduardo Galeano so simply put it, “Many small people, in many small places do many small things that can alter the face of the world.”

The Log Cathedral of Buckhorn, Kentucky, constructed in 1928, is listed on the National Registry of Historic Places. Photo courtesy of the author.

NPR’s S-Town is a literary piece nested in historical truth. Metaphysically speaking, it is ironic that this is much the same way that Appalachia is viewed in the common narrative of contemporary American culture, though in reverse; Appalachia is a historical truth nested in a grotesque, politically expedient, tragi-comedic narrative. That is to say, it is viewed as “a crazy backwards place, full of colorful degenerates with problems and speech patterns that I mostly can’t relate to—though some of them advocate progressive causes, seem to be brilliant, have hearts of gold, etc.” The similar literary grandiosity of S-Town struck me as worth mentioning here, as this is how the “othering” of Appalachia is perpetuated through the mainstream media and outsiders like J.D. Vance (who hope to capitalize on the identity).

I stated earlier in this piece that Appalachia in the enlightened liberal American gaze is something akin to a barometer with which social progress can be measured. However, there is more than a bit of classical Saidian orientalism at work in the way that the American othering of Appalachia occurs. Take a look at contemporary television depictions of Appalachia on programs like “Outsiders” to see what I mean. We are the noble savages at best, the degenerates at worst, to be above all pitied, politicized, and incorporated into the federal agenda of the day which, invariably, all but excludes us from participation.

The author’s grandfather’s Volkswagen. Photo courtesy of the author.

Here is the ugly truth: America is full of shit towns, coast-to-coast and north to south, where Americans experience quite a different reality the suburban and urban elites of coastal cities. In these shit towns, where the water is poisoned, prescription drugs are a plenty, and poverty and unemployment only continue to grow, America continues to ignore the reality of Appalachian social problems. When the occasional pundit or columnist does acknowledged our social problems, invariably they claim we deserve it, or shame us into thinking we created it ourselves. Neither of these solutions correctly addresses the issue.

The time has come for America at large to acknowledge its complicity in making Appalachia the smudge of the country. Appalachians, on the other hand, must rise to the challenges of creating sustainable communities and economic development in our region, thus carrying our culture and identity into the new age.

Shit, as any agrarian will tell you, is excellent fertilizer. Much as John B. was able to draw a fantastical hedge-maze, not to mention a vibrant rose garden, out of the cesspool of Shittown, Bibb County, Alabama, we Appalachians could create wonders from our own well-fertilized shit towns across the eastern and southern United States.

Americans, but Appalachians in particular, need to shift our thinking regarding our neglect of the shit towns across our country. We think of them as cesspools when we should think of them as fertile ground for investment, development, and the prime locus for building strong, sustainable communities in the twenty-first century.

Then, and only then, can we begin to clean up the smudge.

The author’s clock collection at his grandfather’s store in Buckhorn. Photo courtesy of the author.

To support local efforts to effect long term social change in Appalachia, please consider making a donation or getting in touch with one of the following organizations:

Appalachian Community Fund

Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky

Appalachian Regional Commission

Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative

Central Appalachian Regional Network

Mountain Association for Community Economic Development

Appalachian College Association

Appalachian Energy and Environment Partnership

For more humanistic and culturally oriented initiatives, please visit the websites of the Appalachian Studies centers at the following universities and colleges:

Berea College, Loyal Jones Appalachian Center

Eastern Kentucky University, Center for Appalachian Studies

Morehead State University, Appalachian Heritage Program

Morehead State University, Center for Regional Engagement

University of Kentucky, Appalachian Center

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://activisthistory.com/2017/06/22/the-unsettling-of-appalachia-identity-activism-and-appalachian-consciousness-as-filtered-through-s-town/