Lab Diaries #7 - Creating Your Own Super Cool ̶K̶i̶l̶l̶e̶r̶ ̶M̶u̶t̶a̶n̶t̶ Safe to Use Virus From Scratch - Part II

After the extremely boring interesting part I of this article, today I will continue on how scientists create recombinant virus particles in their labs and how much fun they have during the process.

Step 1 - Growing and isolation of the single bacterial colonies

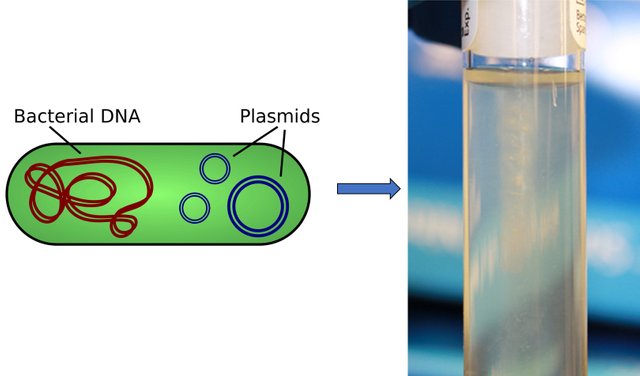

Your plasmid (vector) arrives in the form of bacteria carrying it, which are shipped in the stab culture format, authors Spaully and CNX OpenStax, CC BY-SA 2.5 and CC BY-SA 4.0, respectively

So you have ordered your commercially available plasmid online and it has arrived to your lab. Hm, how do you send a plasmid anyway? They usually arrive already "inserted" into the bacteria, which basically means that what you get is living bacteria, carrying your precious plasmid. Those bacteria are seeded and shipped in a stab culture format, which is simply an ordinary bacterial growth media, called Luria Broth (LB) agar, which has been "stabbed" with the needle with bacteria on it. This means that, instead of just seeding bacteria on the surface of the agar, the manufacturer pierced the agar and placed bacterial cells inside the thick, jelly-like media.

Blob, my new scary monster friend from the lab, author OpenClipart-Vectors, CC0 1.0

Now we need to get our hands on that plasmid that's inside of the bacterial cells, that are inside of this tube containing this strange, weird jelly thing, for which you can only hope it won't turn into some scary, ugly jelly monster from bad science fiction movies overnight!

- Hi @scienceangel, I'm your new friend, Blob!

- I knew drinking THAT much alcohol last night wasn't such a good idea...

We can just take the bacteria, extract the plasmids, and we can go home, right? (whistles) Suuuuure...

To be able to extract enough plasmids for your downstream experiments, you first need to expand/multiply/grow bacteria just to achieve enough number of cells carrying your plasmid. To do that, you need to take the bacteria from the agar stab and seed them in a Petri dish which contains the same growth media as one in the tube with bacteria.

"Streaking" and isolating single bacterial colony

An LB agar plate (a place where your bacterial colonies will grow) is something that you usually make yourself, and it consists of the following ingredients:

- Luria Broth (LB) media - standard bacterial culture media

- Agar - to make a gel-like substance out of your growth media, bacteria cannot digest the agar

- Antibiotic that corresponds to the antibiotic resistance gene within your plasmid - to allow growth of only those bacteria that carry your precious plasmid, since they're resistant to that particular antibiotic

LB agar plate, author Lilly_M, CC BY-SA 3.0

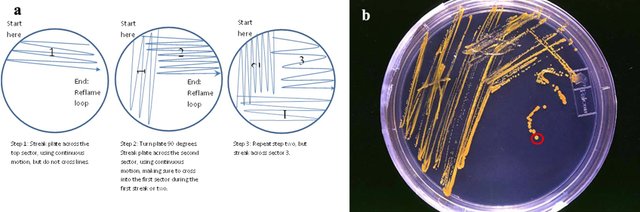

After mixing the growth media powder with sterile water, autoclaving the mixture and adding the antibiotic, the mixture should be poured into the plates and left at the room temperature to solidify. Now you can finally grow the bacteria you ordered, with the goal to obtain single colonies growing on this plate. Why is this important? The pragmatism behind this process is that you always want to extract the plasmid from a colony that represents a result of multiplication of a single bacterium. You do this to decrease possibility of obtaining mutant colonies, which could potentially mean change in protein expression, retroviral plasmid production, etc. What you need to do is to take a toothpick (or a pipette tip), to take the bacteria from the vial (first image) and to gently draw the lines on the surface of your agar plate with a toothpick, just like in the image below (left). After approximately one day of incubation, you should see single colonies growing on your agar plate, like in the image below (right).

Streaking the agar plate (a), and single colonies growth (b), authors Becky Boone and NOAA, CC BY-SA 2.0 and CC0 1.0, respectively

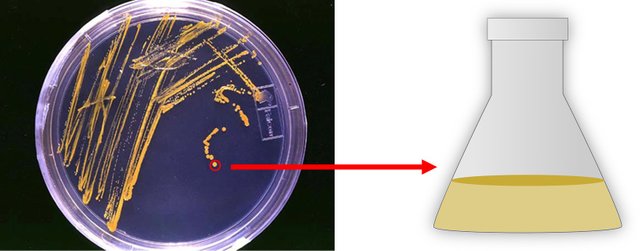

The last sub-step within this step is to multiply the bacteria isolated from a single colony, simply because you need to have enough starting material for plasmid (DNA) extraction. To do this, we take that single colony and transfer it to the appropriate volume of liquid LB media. The volume of growth media of course depends on how much plasmid you want to extract at the end, meaning that you can grow your single colony bacteria in 2 ml tube, or you can even go crazy and go with 1 liter bottle :)

Multiplying the single colony bacteria to obtain enough starting material for plasmid extraction, authors NOAA and OpenClipart-Vectors, CC0 1.0

After we have obtained enough of the starting material for plasmid extraction, we may proceed to the DNA extraction itself, which is usually performed using the commercially available kits, and I'll skip explaining that part in detail here.

Step 2 - Making your own killer mutant safe to use virus particles

The structure of lentiviruses

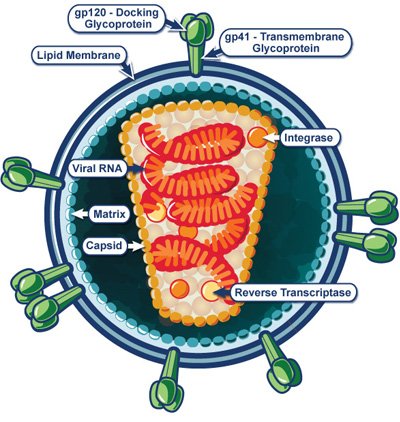

HIV virus structure, author NIAID, CC BY 2.0

Finally the time has come to produce lentiviral particles I need for my super cool experiment.

But, what are the ingredients I need to make a completely functional viral particle? To know that, I first need to have a knowledge of the structure of the lentiviruses, unless I want to mess up my experiment completely!

Each lentivirus consists of three basic structural and functional elements, which are necessary for the infection of the host cell and replication:

1. Viral genetic material, in the form of single stranded RNA - since lentiviruses (such as HIV virus) belong to the retroviridae family of viruses, their genetic material is in the form of single stranded RNA, and once the virus enters the host cell, its RNA is first reverse-transcribed into DNA and then integrated into genome of the host cell

2. Capsid - a protein shell of the virus, protecting its genetic material

3. Viral envelope - some viruses, including lentiviruses, have an additional protective cover around their capsids, usually made of phospholipids and proteins taken from the host cell membrane. It may also contain some viral glycoproteins.

Mixing the ingredients, but in the safe way

To be able to make a functional viral particle, I need to "produce" those three structural and functional elements first.

How do I do that?

Simply by providing plasmids carrying instructions for making each of the component, and mixing them together.

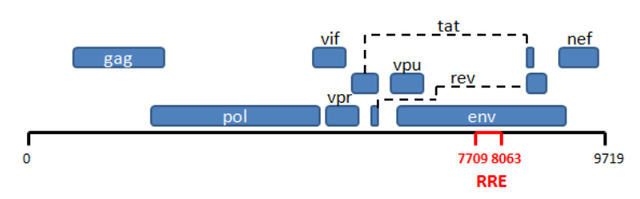

Naturally, in viruses, all genetic components carrying information for production of the functional virus particle are located within the same nucleic acid, like in the image below.

HIV genome, author Jdf2001, CC0 1.0

However, due to the safety concerns, the evolution of the lentiviral technology went in the direction of decreasing the probability of forming of the completely functional viral particles that are capable of producing new viral particles once they have integrated into the host genome.

Nowadays, in the research, lentiviral plasmids of the 2nd and 3rd generation are being used. This means that genetic elements necessary for the functional virus replication are separated into different plasmids, which are dependent between themselves, meaning that only and only when all plasmids are introduced into the host cell, the generation of new virus particles is possible.

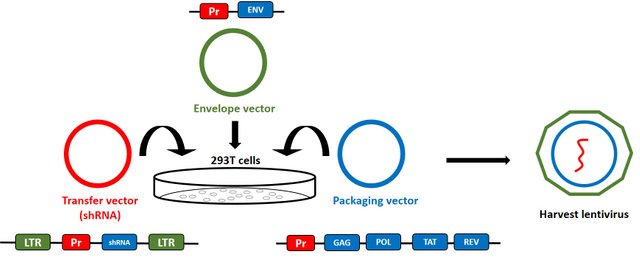

Lentivirus production, author @scienceangel

Back to my lovely experiment. To be able to make complete viral particles, I need three different plasmids, each one of them carrying information for the certain component of the virus. Those plasmids are:

1. Transfer plasmid (vector) with my gene of interest (shRNA) - this is the essential plasmid and it carries the sequence of the shRNA which I want to express in the target cancer cells. The sequence carried within this plasmid is integrated in the host genome. However, this plasmid is created in such manner that is replication incompetent on its own and requires the presence of genetic elements from other plasmids to be able to create new viral particles.

2. Packaging plasmid - carries the elements necessary for making of viral capsid (GAG) and for the viral reverse transcriptase (POL), as well as elements that are crucial for expression of the genes within the transfer plasmid (TAT). The promoter sequence within the transfer plasmid is usually weak, and requires the presence of the strong promoter in order to make the desired shRNA from the transfer plasmid sequence.

3. Envelope vector - carries the elements necessary for making of viral envelope (ENV)

Once I have produced enough quantities of mentioned plasmids (during the steps I talked about earlier in this article), I have to mix them together and "offer" them to the special cell line that is usually used for production of the lentiviral particles, 293T cells, which are human embryonic kidney cells. Once all three plasmid types are in these cells, the information carried within them should combine into functional virus particles, that are, only at this stage, capable of replicating and producing new viruses.

When enough new virus particles are produced, I will collect them from the media in which 293T cells are growing and make concentrated, ready-to-use virus stocks.

Finally, I will use those virus particles to infect target cancer cells and to express the shRNA of interest. Remember - those virus particles are replication incompetent, and they can only integrate into the genome of the host cell line and express (transcribe) the shRNA of interest, but they cannot, under any circumstances, produce new viral particles, because they lack functional genetic elements to do so.

I hope at least 5 people will read this article, and that at least 2 of those 5 will understand its content. As always, I'll be more than glad to answer any question regarding it.

I tried, as always, to simplify the content as much as possible to make science closer to the general audience. However, it is never good loosing yourself too much during the process, because the thin line between simplification and distortion of the facts can be easily crossed.

Richard Dawkins, author Zoe Margolis, CC BY 2.0

In the conclusion, and as a reminder for all the people who might forget this from time to time, I will cite one of the greatest evolutionary biologist of our time, Richard Dawkins:

Science works, bitches!

😎😎😎

Literature

Plasmids 101: A Desktop Resource (3rd Ed.)

Inoculating a Liquid Bacterial Culture

Production of lentiviral vectors

C'mon, be a proper Slavic girl:

I'm getting there XD

you explained the whole process better than my teachers.

Thank you very much @mr-aaron, and thanks for dropping by!

This post has been voted on by the SteemSTEM curation team and voting trail in collaboration with @utopian-io and @curie.

If you appreciate the work we are doing then consider voting all three projects for witness by selecting stem.witness, utopian-io and curie!

For additional information please join us on the SteemSTEM discord and to get to know the rest of the community!

This post was shared in the Curation Collective Discord community for curators, and upvoted and resteemed by the @c-squared community account after manual review.

Hi @scienceangel!

Your post was upvoted by utopian.io in cooperation with steemstem - supporting knowledge, innovation and technological advancement on the Steem Blockchain.

Contribute to Open Source with utopian.io

Learn how to contribute on our website and join the new open source economy.

Want to chat? Join the Utopian Community on Discord https://discord.gg/h52nFrV

Congratulations @scienceangel! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDo not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Hello, as a member of @steemdunk you have received a free courtesy boost! Steemdunk is an automated curation platform that is easy to use and built for the community. Join us at https://steemdunk.xyz

Upvote this comment to support the bot and increase your future rewards!